A Tale of Two Koreas

Kim Jong Un's recent rejection of previous commitments to peaceful unification with South Korea is likely to exacerbate tensions between the two Koreas for a while. However, Kim’s acceptance of two distinct Korean states is unexpectedly realistic. Accepting the current realities of separate states on the Korean Peninsula might be a great leap toward the stable coexistence of two Koreas.

North Korea recently demolished the Arch of Reunification, a monument symbolizing hopes for Korean reunification established after the 2000 inter-Korea summit. Formally called the Monument to the Three Charters for National Reunification, the 100-foot tall arch represented principles of self-reliance, peace, and national cooperation.

This dramatic act follows Kim Jong Un’s December 2023 declaration renouncing previous commitments to peaceful unification with South Korea. He labeled South Korea an “invariable principal enemy” to be “completely occupied” in any war, calling for constitutional revisions codifying this hostile stance. Kim also abolished agencies pursuing inter-Korean dialogue.

Such belligerence, coupled with missile tests, has led some experts to conclude that the Korean Peninsula faces its most precarious conditions since the 1950 North Korean invasion triggered the Korean War. Robert Gallucci, a former lead U.S. negotiator during the 1994 North Korean nuclear crisis, has warned that nuclear war could erupt in Northeast Asia in 2024.

Whether these provocations indicate Kim intends war or seeks negotiating leverage remains unclear. Large-scale conflict appears unlikely. But, without careful crisis management, minor clashes may escalate into a full-blown crisis. Despite differing perspectives, one thing is clear: mounting uncertainty and instability on the Korean Peninsula can further destabilize East Asian and global politics.

Is North Korea Bluffing Again?

Over the years, North Korea has honed its use of brinkmanship, skillfully escalating threats and provocations to create crises, while simultaneously seeking concessions to avert full-scale conflict. Recent belligerent rhetoric and events, such as the launch of multiple cruise missiles by North Korea in January 2024, can be interpreted as another instance of such brinkmanship.

This time, however, the situation appears more ominous. Kim has already ordered constitutional revisions removing references to unification and abolishing inter-Korean cooperation agencies—actions beyond mere words. These moves suggest the North Korean regime is fundamentally abandoning reconciliation efforts and slamming the door shut on engagement with the South for the foreseeable future. This suggests we are entering a new era marked by persistent division instead of the historical cycle of fluctuating tensions.

The demolition of the Arch of Reunification underscores Kim Jong Un’s commitment to diverge from the path of his grandfather and father, who envisioned and worked towards the unification of the Koreas. This act signifies a clear departure from the pursuit of cooperation with Seoul, as Kim opts for a trajectory that explicitly abandons any previous commitments to peaceful reunification.

Furthermore, Kim’s speech in September 2023 hinted at a new Cold War alignment, positioning North Korea alongside China and Russia, and in opposition to the U.S.-led bloc, including South Korea. By casting the two Koreas as entrenched in opposing camps, Kim views hostility with the South as a permanent and unavoidable state of affairs, regardless of South Korea’s leadership. This perspective eliminates any hope for immediate cooperation with a South Korea that aligns closely with the United States, dashing the aspirations of those in the South who supported the “Sunshine Policy” of engagement with the North.

Enhanced Nuclear Blackmail for Recognition

One of the most alarming policy shifts in Kim’s messages is North Korea’s more aggressive nuclear policy toward South Korea. Previously, North Korea implied it would not target the South with nuclear weapons due to their shared heritage. However, in 2022, it adopted a legal stance allowing the first use of nuclear weapons if it perceives a threat, and in September 2023, it constitutionally declared itself a permanent nuclear power. By officially rejecting reunification, Kim has indicated a willingness to disregard their shared history in military strategy, viewing South Korea as a foreign adversary.

The year 2024 brings heightened concerns as Kim might escalate tensions to secure recognition as a nuclear power, emulating the path taken by India and Pakistan. Their nuclear tests in May 1998 challenged global nonproliferation norms, drawing international condemnation and sanctions. However, the 1999 Kargil War, which occurred from May to July 1999, had a significant impact on the diplomatic process and strategic interactions between the U.S., India, and Pakistan. As the conflict could escalate into a full-scale war, potentially involving nuclear weapons, the U.S. government shifted its diplomatic efforts from nonproliferation and a test ban to crisis management and de-escalation.

The turning point came with the shift of the U.S. global strategic priorities after the 9/11 attack in 2001. To counterbalance China’s ascent and secure Pakistan’s assistance for the war in Afghanistan, the Bush administration lifted the remaining sanctions against both countries. This action effectively acknowledged their status as nuclear-armed nations. Further solidifying this shift, in 2005, President Bush and Indian Prime Minister Singh signed the groundbreaking U.S.-India Civil Nuclear Cooperation Agreement, despite India’s refusal to join the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). In a significant development in 2008, the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) relaxed its regulations to permit nuclear commerce with nations outside the NPT, enabling India to participate in global civil nuclear trade. This series of events, culminating with the NSG’s decision, marked a crucial turning point that cemented the strategic partnership between the United States and India, acknowledging India’s nuclear capabilities on the world stage.

North Korea seems intent on a similar trajectory, possibly initiating limited but lethal military action against South Korea to create a strategic crisis. This could compel international intervention to mitigate escalation risks from potential nuclear confrontation on the Korean Peninsula. Despite repeated nuclear threats, if North Korea skillfully keeps things from an uncontrolled spiral, as India and Pakistan did with measured actions amid tension, it may work positively to earn global confirmation as a de facto nuclear power in the long run.

Of course, nuclear brinkmanship carries the risk of uncontrollable escalation, but as the Kargil War illustrates, limited conflicts can enhance the stature of nuclear-capable states if managed astutely. Kim Jong Un may be betting similarly—that some conflict is worthwhile if it finally accrues for North Korea the prizes of nuclear prestige, deal-making concessions, and long-term stability.

North Korea might view the year 2024 as an optimal moment to enhance its nuclear bargaining power. The U.S. is entangled in Ukraine and the Middle East and pivoting its attention toward Taiwan, while its domestic politics center on upcoming elections. Currently, South Korea, China, and the U.S. find themselves without viable strategies to effectively address North Korea’s advancing weapons programs, either through dialogue or sanctions. At the same time, North Korea is strengthening its military ties with Russia.

All these predictions may prove wrong, but one thing seems clear: Kim Jong Un is determined to cement North Korea as an undeniable nuclear power, amassing capabilities too costly to dismantle. The likelihood of North Korea willingly giving up its nuclear arsenal appears increasingly slim, underscoring the complexity of achieving denuclearization and the potential for heightened tensions on the Korean Peninsula and beyond.

Waning Trust in the U.S. Security Promises

Shifts in U.S. foreign policy, particularly with possible pending changes in administration, further complicate the evolving dynamics of the Korean Peninsula. Security cooperation between the United States, South Korea, and Japan has heightened as a result of the growing nuclear and missile capabilities of North Korea. This includes regular high-level meetings, like the Camp David Summit, focused on improving deterrence and readiness. The U.S.-Korea Nuclear Consultative Group has been established to involve Seoul more in U.S. nuclear planning. A new instant warning system can quickly alert allies to North Korean missile launches. Joint military exercises, including aerial drills with U.S. B-1 bombers, have increased following North Korea’s extensive ICBM tests. These combined efforts underscore a unified front against North Korean provocations.

However, confidence in U.S. security commitments is waning in South Korea. Polls indicate a growing number of South Koreans support the development of their country’s own nuclear arsenal, despite the potential international backlash. With North Korea’s relentless advancement of its nuclear and missile capabilities, over 70% of South Koreans now support having their own nuclear weapons, regardless of potential economic or diplomatic consequences. A significant portion shows a preference for self-managed nuclear deterrence over hosting U.S. nuclear weapons. Furthermore, a 2023 survey revealed a sharp decline in American public support for U.S. troop commitments in South Korea, dropping from 63% to 50% in just one year.

While public opinion does not directly shape policy, the strong preference for an independent nuclear arsenal in South Korea presents a significant strategic challenge for its leaders. This issue is compounded by waning American public support for defending South Korea. Changing public sentiment and opinion about risk tolerance pose a severe challenge to nuclear nonproliferation efforts on the Korean Peninsula.

Diplomacy or Deterrence: Weighing Trump’s North Korea Strategy

Should Donald Trump be reelected, there is speculation his administration may pursue a “freeze-for-relief” policy with North Korea. This approach, which Trump has considered but denied, would permit North Korea to retain its nuclear weapons in exchange for economic incentives to halt further development. Such a policy can bring North Korea to the negotiation table. It can also be a strategic move against China, as Beijing views a nuclear-armed North Korea turning against it as a critical concern. By addressing the North Korean issue, Trump could refocus efforts on countering China’s regional influence.

However, this policy risks empowering North Korea, potentially undermining confidence in U.S. security commitments in South Korea and Japan. Concerned about their security, these two countries might consider developing independent nuclear capabilities. Trump’s transactional view of alliances, particularly defense costs and troop deployment, could further strain relations with South Korea and Japan, jeopardizing decades of established trust and cooperation.

Despite potential drawbacks, the “freeze-for-relief” policy could gain domestic support, with many Americans favoring diplomacy over demanding complete denuclearization. A Chicago Council on Global Affairs poll revealed that 76% of Americans support a peace agreement with North Korea if it halts nuclear development, and over half favor establishing a U.S. diplomatic presence in Pyongyang. While 24% oppose any agreement allowing North Korea to retain nuclear weapons, the prospect of North Korea’s complete disarmament is increasingly seen as unrealistic, given its existing arsenal and continued expansion. North Korea already possesses an estimated 45 to 55 nuclear warheads and continues to expand its arsenal, projecting over 200 warheads by 2027. Its nuclear knowledge cannot be undone, making immediate disarmament unlikely.

Effective diplomacy requires focusing on managing deterrence and containment rather than unrealistically insisting on immediate, complete denuclearization. Adopting a “balance of terror” strategy, such as the MAD system, could facilitate nuclear agreements with North Korea, like Cold War-era U.S.-Soviet negotiations. The Biden administration has primarily focused on strengthening the alliance between the U.S., South Korea, and Japan while hoping sanctions might pressure Kim’s regime to collapse or at least lure it to dialogue. However, history shows that sanctions alone are unlikely to achieve complete nuclear disarmament or regime change in North Korea.

Allies must respond firmly to North Korean aggression, but maintaining open communication is essential to avoid unintended conflicts. Without dialogue, minor incidents can escalate into larger conflicts. Completely isolating North Korea is impractical despite its authoritarian nature and human rights violations. Recognizing North Korea’s internal decisions and security concerns is vital to preventing accidental military clashes. Over-reliance on military deterrence alone could perpetuate a cycle of escalating mutual threat perceptions and arms buildups.

The outcome of the forthcoming U.S. presidential election is still uncertain. However, the next administration must uphold strong alliance commitments and remain open to dialogue with North Korea, especially as the chance for Korean reconciliation fades. History suggests openness to innovative approaches, such as a “two-state solution,” may yield new paths forward.

Taking A “Two-State Solution” More Seriously

Kim Jong Un’s stance, which sharply delineates North and South Korea as separate adversarial entities, is likely to exacerbate tensions between the two Koreas for a while. However, Kim’s acceptance of two distinct Korean states is unexpectedly realistic. Accepting the current realities of two separate states on the Korean Peninsula might be a great leap toward the stable coexistence of two Korean states.

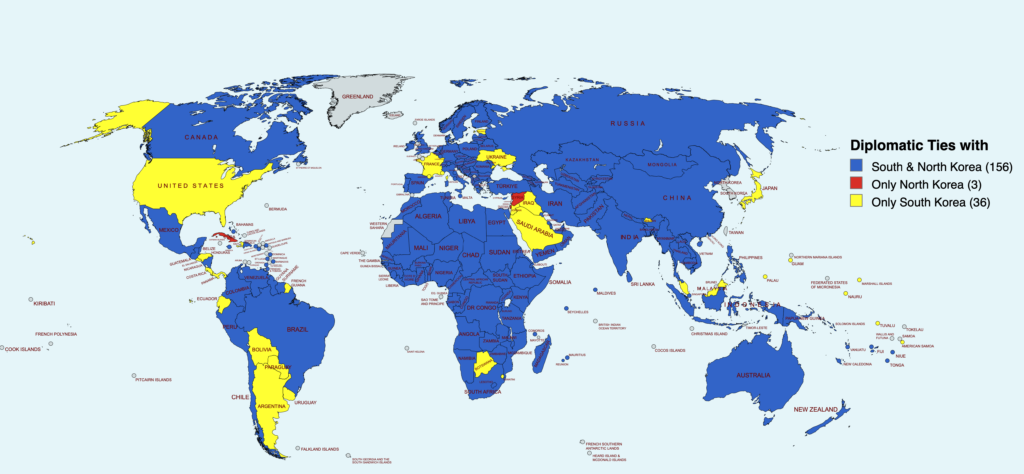

Since the end of the Cold War in the 1990s, both Koreas have gained significant international recognition, with South Korea and North Korea establishing diplomatic relations with 192 and 159 UN member states, respectively. Despite this, neither government recognizes the other’s legitimacy over their respective territories and populations. This persistent mutual denial, fueled by the dream of eventual reunification, perpetuates tension and obstructs diplomatic progress.

However, there is a growing acceptance within South Korea of the reality of two separate states, a shift reflected across different age groups. Polls indicate that support for reunification is waning, whereby acceptance of a more pragmatic coexistence is preferred throughout age groups. However, some political groups still advocate for maintaining the narrative of a “special one nation” partnership to further inter-Korean progress.

Indeed, South Korea’s Constitution defines its territory as “the Korean Peninsula and its adjacent islands” (article 3) while obligating the pursuit of “peaceful reunification based on the basic free and democratic order” (article 4) as a constitutional imperative. This objective of creating “one nation, one state” is deeply ingrained in the nation’s legal framework, making the pursuit of reunification a constitutional duty across the political spectrum. Changing this stance would necessitate broad political agreement.

Proposing a constitutional amendment to acknowledge North Korea as a separate sovereign entity would likely spark intense political debate. Conservatives might view such a change as an assault on a core element of Korean identity and the long-held aspiration for reunification. At the same time, progressives could be criticized for abandoning the ideals of peaceful reunification.

Despite these political challenges, amending the Constitution is a necessary step for progress. The current inability to formally recognize North Korea as an independent state hampers any significant advancement in inter-Korean relations. Reality suggests that the vision of a unified Korea, completely absorbed by the other side, is increasingly improbable.

Acknowledging this political reality could open up opportunities for practical engagement based on the acknowledgment of two sovereign states. It would allow for discussions on cooperation aimed at peaceful coexistence and the eventual healing of a divided nation. The difficulties of constitutional change are a small price to pay for equipping future generations with the flexibility to pursue realistic and productive paths forward, grounded in current realities rather than outdated constitutional aspirations.

The success of a “two-state solution” on the Korean Peninsula depends on regional powers’ mutual recognition and cooperation, including China, Russia, Japan, and the United States. These nations must work together to de-escalate military tensions in the region. While North Korea’s nuclear program is likely to persist, initiatives such as arms reduction and the establishment of crisis communication hotlines are essential to prevent potential conflicts. A collective effort to minimize military provocations could create a conducive environment for diplomatic engagement and economic collaboration, helping both Koreas adapt to a stable yet divided existence. Diplomatic normalization between Pyongyang, Washington, and Tokyo is a more constructive approach than ongoing hostility, setting the foundation for a relationship between two distinct but interconnected Korean states that promotes enduring stability.

Ultimately, military measures alone are insufficient to address the escalating crisis. True and lasting peace necessitates a slow process of rebuilding trust between all involved parties. Although it presents a significant challenge, a well-thought-out mix of sanctions and incentives, underpinned by strategic diplomacy, has the potential to foster meaningful advancements, even in the most difficult circumstances.