After Apocalypse

On Black Futurist Inquiry as survival technology.

THIS ESSAY IS PART OF THE SPECIAL ISSUE “AFTER LIFE: IDENTITY AND INDIFFERENCE IN THE TIME OF PLANETARY PERIL.” IT FEATURES PAPERS PRESENTED AT THE INAUGURAL SYMPOSIUM OF THE DEMOCRACY INSTITUTE AT THE AHIMSA CENTER AT CAL POLY POMONA, WHICH WAS CO-SPONSORED BY THE INSTITUTE FOR NEW GLOBAL POLITICS, IN MARCH 2023.

Belief

Initiates and guides action—

Or it does nothing.

Books of the Living, in Parable of the Sower (1993)

We don’t really know what our beliefs are until they are tested, when our lives, livelihoods or personhood are threatened. And when we are tested, what actions will we take? Some of us live under these threats to existence daily as freedoms and rights remain elusive or are curtailed deliberately clutched back through legislation, terror, and benign neglect.

To be clear, whatever the dominant middle-class culture in this contemporary moment thinks of as apocalypse has already occurred throughout history, across timespace and through multiple genealogies/genomes/geographies. Nearly every extant contemporary society (national park, monument, neighborhood, nation, sports arena) is built on the detritus of past eras. First world conveniences—perceived ownership, occupation, liberty—are predicated on the forced and violent oppression and/or extraction of resources (people, goods, spices, skills) from some other locale on the globe. We all occupy contested spaces, we are interconnected—all implicated and therefore all responsible in our shared futures (though we are not all equally responsible for nor benefited from all past indiscretions).

A refusal to take on the monumental task of imagining the future will have deleterious impacts on all of us. Our liberation is always already based on the degrees to which others can also be whole and free.

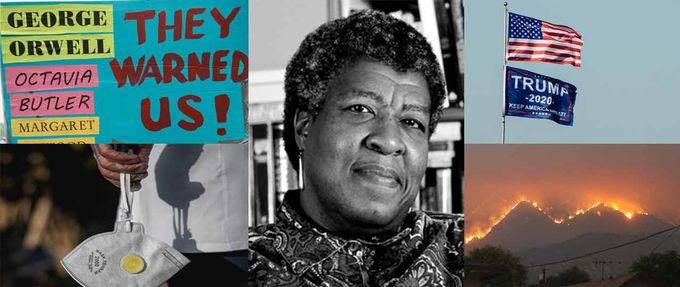

Octavia E. Butler (1947–2006), an award-winning speculative fiction Black woman writer from Pasadena, California, warned us through her fiction, essays, speeches, and notecards—her very existence. Born during the geopolitical tensions of the Cold War, Butler noted that she grew up in Jim Crow California. She watched her mother, a domestic worker, enter back doors, conveniently growing deaf and mute to the jibes and macroaggressions from members of wealthy families.

In a 2000 essay for O:Oprah Magazine, Butler recalled a time when she and her mother were “‘staying on the place,’ as it used to be called, living in her employer’s home and having no home of her own” and in some ways in a constant state of precarity. These facts of her biography are often overlooked or ignored, yet the realities cannot be erased. Butler’s family migrated from Louisiana to Los Angeles in 1930 as part of the Great Migration.

Her family left sharecropping on a sugar plantation to live what I call plantation style in a place that had racism but no racists. Her mother, Octavia Margaret Guy, grew up as the eldest child in her family. She only had three years of formal education, having been plopped down into the elementary classroom arbitrarily based on age. With few other opportunities, Butler’s mother was forced to work as a maid beginning in childhood and throughout her life. In fact, she cleaned homes for the people who lived in what would later be San Marino, a notorious sundown town in the same city where Butler’s papers and literary manuscripts are currently stored and accessed by researchers. The details are available in public records even while Butler’s bequeathal represents a kind of unacknowledged public reckoning.

In the decade of Octavia’s birth, 90 of the 108 Black residents of San Marino and three decades later in 1970, 19 of its 24 Black residents were female, suggesting the Black population was mostly made up of live-in domestic workers. Butler witnessed and documented reality from Civil Rights to civic resentment and noted the pronounced backlash that always takes place whenever things become slightly more equitable. The 45th presidency represents another backlash swing.

All of Butler’s “predictions” were cautionary tales based on the realities that she experienced, encountered, and meticulously researched—all things that needed attention and intervention. As Literature and Ethnic Studies scholar Dr. Shelley Streeby has noted, Butler had already warned in 1989 of “the ecological catastrophe waiting in the wings or already in progress.” Butler had “prophesied that the world would face slow violence, otherwise described as ‘a series of chronic problems, not a big, acute crisis,’ and that ‘we’ll be dealing with it for a long long time—far longer than anyone alive now will live.’”

Shelley Streeby, Imagining the Future of Climate Change: World-Making through Science Fiction and Activism (University of California Press)

Before it became available to researchers in late 2013, the Butler Collection was the most highly anticipated and is today the most accessed collection of literary manuscripts housed at The Huntington. It is comprised of over ten thousand individual items contained in over 350 boxes. Her lifetime of work will take a lifetime for me to continue to unpack to map and decipher as it unfolded. Before and since founding the Octavia E. Butler Legacy Network in 2011, I have known how beloved Butler is, but also how people tend to mythologize Octavia E. Butler almost to the point of fetishization and tokenizing.

She and her characters are read out of context as if they can neatly fit into the hero’s monomyth and can represent an upward, rags-to-riches, feelgood story to assuage our willful ignorance about the indignities many of our ancestors endured so that we can exist today. People project their needs for security and certainty onto a version of the world that brings the most comfort. The message is that marginalized folks should just shut up about the past, that our current achievements erase past wrongs, and instead of working toward greater acceptance, we should be happy to be allowed into formerly inaccessible places.

When people think she predicted the future, sometimes, it is simpler to just thoughtfully nod and agree rather than offer more detailed analysis of her predictions as the dominant culture is finally taking notice. But the truth is more stark and more compelling. Butler’s novel Clay’s Ark, published in 1984, imagined the year 2021 as a moment when people are forced to live in isolation to stop the spread of a contagious pathogen. The book is set in the California desert where person to person contact is one of the main ways people are infected, transforming the human species and way of life forever.

In Butler’s Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998), the world is beset with climate disaster, widespread unemployment, poverty, and shortages of water and gasoline. These books begin to unfold in 2024, a year that is rapidly approaching. The book’s protagonist, Lauren Oya Olamina, was born in 2009 and is one of the children who attended school at home and is at risk of gun violence.

That future is rapidly approaching, but not all of it is inevitable or on schedule. People often inquire about whether Butler predicted the future, when, really, she was exploring the three most common tenets or conventions of science fiction: “What if?” “If Only” and “If this goes on…..”

These are the kinds of open-ended questions to ask about the possibilities that await us if we dare to hope; about what we desire and long for; and (most often) about what hazards await us if we are not careful, if we do not choose collective action over momentary inconvenience. These are the hallmarks of speculative fiction as Butler expanded the field as the only Black woman writing in the genre for a time.

One day, when they ask our students, their children, chosen families and examine the artifacts of the 2020s, people may still be saying that award-winning Black woman speculative fiction author and cultural figure Octavia E. Butler predicted the future. People regularly call her a seer or an oracle who could tap into the imaginal streams of spacetime to pluck out the pebbles of wisdom that could warn or guide her readers forward. Indeed, it can feel like she was able to see the paths of possible timelines. The truth of Butler’s “predictions” and how she arrived at them are more methodical, methodological, and compelling than just a magical gift of intuition.

The driving force for her acquisition of skills or knowledge—her nearly superhuman ability to write “stories compellingly told” comes from something she called her “positive obsession.” Positive obsession also represented an entity in Butler’s personal life, a force that she was driven by in her life to write: “It is about not being able to stop just because you’re afraid and full of doubts. Positive obsession is dangerous. It’s about not being able to stop at all.”

The original 1989 Essence article “Birth of a Writer” (a title given by the magazine editors) was always, for Butler, the autobiographical essay “Positive Obsession.” Butler had been thinking and writing about positive obsession for nearly ten years before she fictionalized it and described its function through Lauren Oya Olamina as positive obsession that “Blunts pain, / Diverts rage, / And engages each of us / In the greatest, / The most intense / Of our chosen struggles.” In the commentary after the essay, Butler concluded: “I have no doubt at all that the best and the most interesting part of me is my fiction.” At present, over 17 years after her unexpected death, people are more interested than ever in her fiction and her life.

I was trained in a field that has gathered clinical data that suggests that sickness is not limited, nor exclusively individual, biological, and chemical, but instead is fostered by the culture out of which the symptoms arise. As liberation psychologist, Mary Watkins wrote:

“If, as depth psychologists, we keep psychopathology at the heart of our concern, but widen our conception of its cause and expressions to include culture, then to address psychopathology, to be in dialogue with it, our attention turns to world and community as well. The symptom as it appears in the individual points us also toward the pathology of the world, of the culture. When we are not able to follow the symptom into the culture on which it comments, we misinterpret its protest, and negate its voice [emphasis added].”

Perhaps we can see this most clearly in extreme examples. As with the post in post-traumatic stress disorder, the stresses and traumas of apocalypse are ongoing, ubiquitous, and complex. We call this kind of ongoing and complicated PTSD “complex” in both the clinical sense and in the immediate attempts to grapple with it. Trauma represents a tear in the fabric of existence; rupture always recenters the future, compounding and exacerbating the symptoms of trauma.

From contested borders to notions of the so-called minority of the “Global South,” which actually comprises the global majority, marginalized peoples have always spoken for themselves. We have always been the first to encounter the paradigm shifting circumstances for Change (an archetype), like the consequences of war, famine, climate disaster, economic and employment shifts, the prison industrial complex and disparities of all kinds. Impact is always more important than intent. Whether something is violent depends upon who you are, where you are geographically, your proximity to the dominant culture and its inherent privilege. These are just facts.

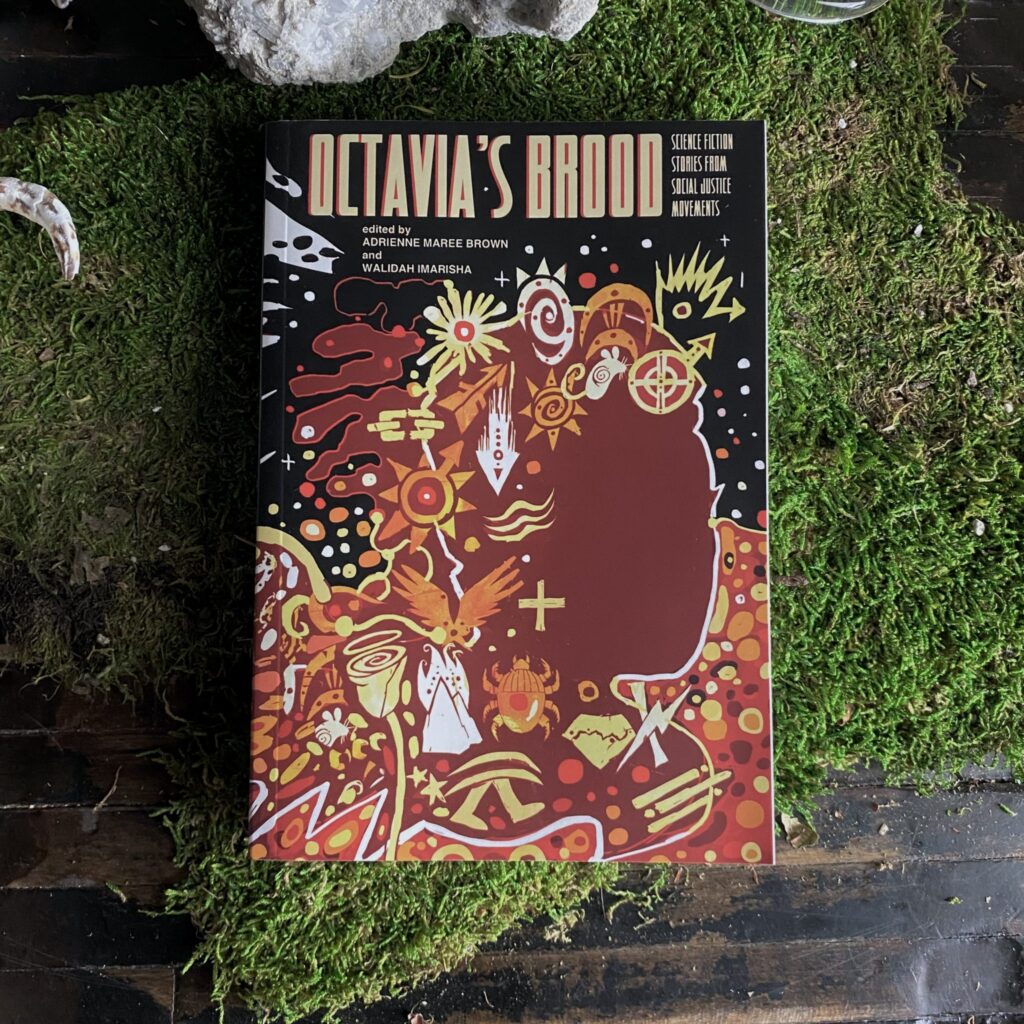

In Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements, Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown wrote that social justice organizing is science fiction, and that our ancestors bent reality to dream of the kinds of futures that they longed for on our behalf. All liberation begins with a spark of survival that shifts the cultural mythologies of devaluing difference. Anytime we imagine worlds without poverty, disease, prisons, and discrimination, we are engaging in a speculative and visionary kind of collective action.

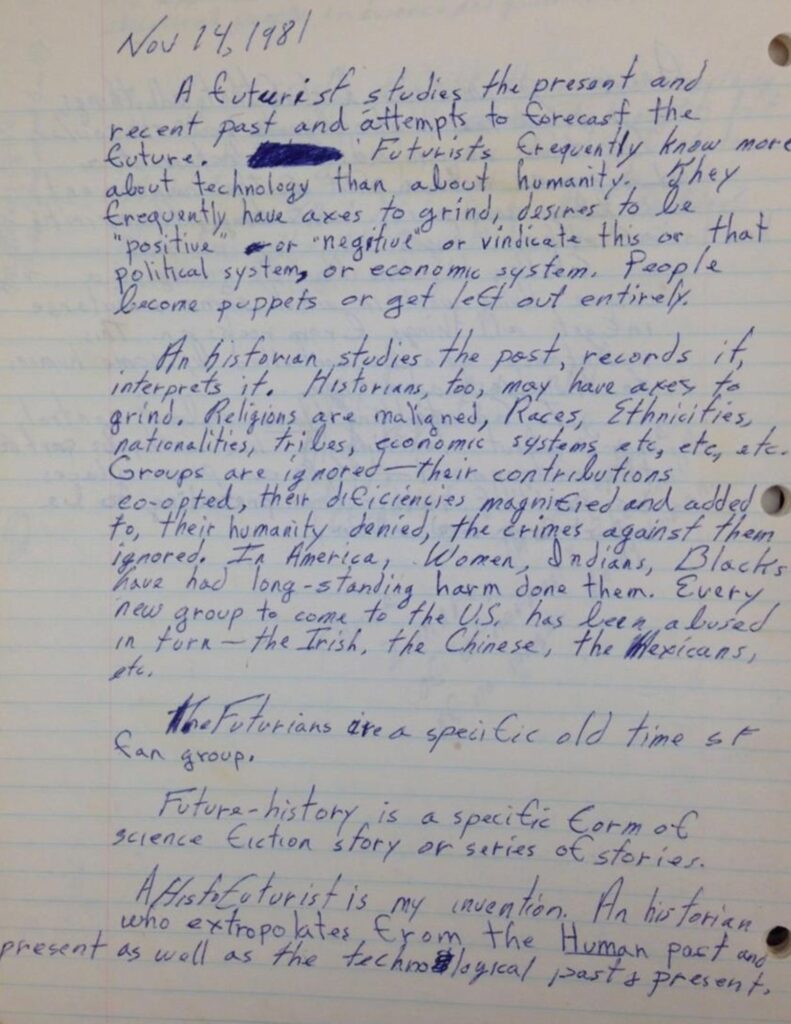

Octavia E. Butler considered herself both a part of and outside of time, a person who gathered data and made observations about human beings and their impact on the globe and one another long before the term “Afrofuturism” was coined in an interview from the 1990s. On November 14, 1981 she wrote: “A HistoFuturist is my invention. An historian who extrapolates from the Human past and present as well as the technological past + present.”

W.E.B Du Bois (1868–1963), the sociologist and author of speculative fiction, wrote an apocalyptic short story called “The Comet” in 1920 at the age of 50 in his aptly entitled collection Darkwater: Voices From Within the Veil. In the short story, the Black male protagonist is ordered to go into a basement storage area to retrieve something before an impending comet hits and is locked inside a vault. Like Butler’s mother, the man is treated as a nameless messenger, a body to complete a task, not spoken with directly. When he emerges to find everyone around him dead, he searches New York City for the survivors and eventually encounters a wealthy white woman. Du Bois is asking, what would happen if a Black person was one of the last people on earth?

The social customs of division marked by the time period in which the short stories are set cease to be as relevant when a white woman and a Black man think (for a time) that they may be the last living people on earth. Without the surveillance of segregation, the so-called social order collapses.

In this context, W. E. B. Du Bois is writing visionary fiction with a HistoFuturist impulse. He knew intuitively that the stories that are erased, neglected, and disregarded are the ones that need to be fleshed out. As a scholar of speculative fiction, hidden histories, and how we continue to examine (or ignore) existing inequalities, are always at the forefront of my attention. And as an educator, a comparative mythologist, depth psychologist, and parent, I am always wondering what we have inherited and what we leave behind to future generations.

Finally, there are always legacies, multiple narratives that overlap, and contradict one another, but there was more confluence than discord at the Democracy Institute’s Inaugural Symposium. The presentations were curated with such care, that many ideas seemed to be pulled as if from collective un/conscious, a shared undercommons both brought to bear in the room and erupting within my body. My heart raced, body sweat, and dry mouth all left me feeling disoriented and dizzy, as if diasporic vertigo is to be expected. What other response might we have when the words of our heart enter the room via the lips of a very new colleague or distant acquaintance? What happens to our senses as we make room for the kinds of invigorating synchronicities that unfolded that weekend?

We were encapsulated in the building, all of us entered a kind of inverted underworld on the lower level of the conference center not unlike the vault of “The Comet,” while thick torrents of rain—called atmospheric rivers—cascaded from the heavens as volleys of intermittent emergency alerts took over everyone’s devices to report a missing (and later found) 93-year old woman.

The universe and this timeline seemed to say:

Technology will not save you

and may interrupt your sense of safety at any moment.

If it can speak to you unbidden,

so can it regard your inner thoughts and utterances

Black and Brown bodies are still missing, missed

But we remain unprotected, undiscovered countries, scattered and decomposing

Under threat

Made abject, and uncompensated

These spaces were not made for us

and yet we exist here, peacefully and with resolve.

Generate your own

body heat,

be unruly

Burn on the inside, be passionate,

even while you are perched in the pit of the Underworlds

Find your own reasons for being

Drown in one another

as the rivers flow through the sky

dusting snowcapped chaparral delights

After Life: Identity and Indifference in the time of Planetary Peril was an embodied and evocative space for the kinds of social justice organizing that Imarisha and brown curated. I was the final presenter on the first day so I listened for throughlines trying to highlight patterns as we gathered and shared them. I wanted to prod, expand, question, and draw out some of the themes intentionally.

Observing, with embodied listening for what isn’t being spoken, reading between the lines is a praxis for surviving apocalypse because it is less complicated than disentangling the past, present, and future. While discussing the life and work of Octavia E. Butler, African American feminist scholar, writer, and activist Moya Bailey and I have described this as a kind of “palimpsestuous memorialization.” It is as if we are trying to read the nearly erased passages underneath the most prominent layers of text. These are some of the features of what I call Black Futurist Inquiry: beginning with the underlying questions of how Black people specifically, and other marginalized peoples generally survive in the futures we envision since we were never meant to survive as whole or intact.

Race is a colonial construct created to dole out privileges and justify inequality. The womanist impulse to dwell at the crossroads and intersections of survival is always at the core of resistance to the original narratives of inferiority and deficit postures. Whereas colonialism and imperialism are built on hierarchy by individualism, subjugation, and extraction of wealth, Black Futurist Inquiry might be a revaluation of human capital that is allowed to be fully inhabited, and in spite of the material conditions of the present. If Black women and children, for example, are uplifted and in possession of everything they need to survive whole, then the resources for every other person in a communal ethically sustainable sense must also be available for other people to survive. As I have already stated, Butler reminded us to extend our awareness to the deeply interdependent relationships we must have with the planet and others to survive together.