Palestine and Russia

Across the globe, a mounting consensus has condemned Israeli actions in Gaza as genocide. But this condemnation is not focused on Israel alone. Critics increasingly see the war as evidence of the hypocrisy and illegitimacy of American power. The conflict is accelerating a global realignment in favor of Russia, where Muslims, mobilizing in the name of Palestinian solidarity, are playing a critical role.

On October 29, hundreds of young men stormed an airport in Dagestan, along Russia’s North Caucasus frontier. They descended upon the site after social media warned that a flight from Israel would be landing at Makhachkala. Amid shouts of “God is Great” and anti-Jewish and anti-Israeli slogans, the rioters broke through security barriers seeking Jews to assault. Discovering that no passengers had entered the airport, they stormed the tarmac. They then tried to attack the plane. The authorities eventually regained control and put an end to the violent chaos. The terrorized passengers barely escaped physical harm.

This shocking event evoked memories of the anti-Jewish mob violence that gave the world the fearful Russian word “pogrom.” This event bore dreadful similarities with pogroms in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the tsarist empire and its successor states. But there were also crucial differences.

Historically, pogroms erupted in the western territories of the empire in what is now Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Poland, Lithuania, and southern Russia. But not in the North Caucasus, where Jewish communities had traditionally been spared (until very recently) such recurrent violence. Elsewhere, pogromists had accused Jews of “killing Christ” or “stealing” Christian children for their rites. In this instance, the assailants in Makhachkala instead pledged solidarity with Palestinians under Israeli siege following the Hamas attack of October 7.

Everything about this incident was unprecedented in the Russian context: the attackers risked police repression; they selected as their targets Israelis and Jews; and, crucially, they justified their actions as a defense of suffering Palestinians.

The Makhachkala pogrom brought to the surface a type of anti-Semitic mobilization that had not previously been very visible in this corner of the North Caucasus. At the same time, it exposed a broader shift in the way the Palestinian cause resonates as a global political commitment, including for Russia’s Muslims.

Though unexpected and exceptional in many ways, this episode can serve as a guide to forces that have been been churning below the surface of events in Russia—with crucial implications both for Russian politics and the emerging contours of a post-American global order.

The Israeli destruction of Gaza has proved a godsend for the Kremlin. Shifting attention from Russia’s own atrocities in Ukraine, it has also set the stage for the assertion of Russian leadership in the Middle East and beyond. For Russia’s Muslim leaders, intensifying global outrage at the killing of Palestinians by Israeli forces with American weapons has given leverage to expand their influence in Russian politics—and in the world.

Remembering Palestine, Forgetting Chechnya

It is tempting to interpret the Makhachkala pogrom as a sign of Moscow’s weakness. This view has a certain appeal given the turbulent history of the North Caucasus, where Russia has fought two wars since the collapse of the USSR to retain control.

But the opposite may be the case: a closer look at the Kremlin’s engagement with Muslim elites reveals how Russian authorities have successfully adapted the Palestinian cause to their own purposes. The war has emerged an opportunity to demonstrate that Russia stands on the side of the world’s Muslims against a hypocritical West.

In encouraging solidarity with Palestinians, Russian authorities were quick to redirect responsibility from local actors. Officials in the North Caucasus pointed to “provocateurs” working from abroad to incite this violence, while celebrity mixed martial arts fighters from the region such as ex-UFC champion Khabib Nurmagomedov spoke up in their defense. Similarly, Moscow blamed “interference from outside,” pointing to “efforts by the West to use events in the Middle East to cause a schism in Russian society.” Speaking at a gathering of his National Security Council on October 30th, Vladimir Putin directly accused Ukraine “of trying to inspire pogroms in Russia at the direction of its Western protectors.”

Yet a growing commitment to the Palestinian cause has not been a top-down process dictated by Moscow. Interest in Palestine has been uneven among citizens of Russia. But for Russia’s twenty-million-plus Muslims, in the Caucasus and beyond, the plight of the Palestinians has attracted more and more attention over the last decade.

As the Muslim scholar Zilia Aliautdinova emphasized to Russian-language followers on her Instagram account just days into the war, “Events in Gaza and southern Israel are our pain and sadness.” “Be the voice of Palestine,” urged another Russia-based female expert on Islamic law, Ustaza Iman, on her Instagram page.

Importantly, much of this engagement has taken shape within Islamic institutions that enjoy state support. For the Kremlin and Muslim elites alike, these organizations are important because they not only manage Muslim clerical personnel and mosques—they also sustain contacts with Muslims abroad. This is no small proposition for Muslim communities that must still contend with the legacy of nearly seven decades of Soviet atheism and relative isolation from foreign Muslims in the twentieth century.

There has been no single response to the war in Israel/Palestine from the Muslim communities that dot the Russian landscape from St. Petersburg and Moscow to the Far North and Siberia. The young men who attacked the Makhachkala airport clearly occupy one radical end of a complex spectrum of reactions. Viewed as a whole, though, Muslim opinion in Russia reflects increased identification with Palestinian suffering—and a growing expectation that their religious and political leaders should act on the global stage to address the crisis, not just for Palestinians, but for Muslims everywhere, and, more abstractly, for a global vision of justice.

None of this began only with the October 7 Hamas-led attack on Israel. For Russian leaders seeking influence among the world’s Muslims, Palestinian advocacy is not a new issue. Their efforts build upon a lengthy history in which Russian elites have positioned themselves as both exemplary Orthodox Christians and allies in the anti-imperial and anti-colonial struggles of Muslims. At the same time, Russian elites—including the heads of the Russian Orthodox Church—have long claimed the right to have a say on the future of the Holy Land.

In leading the brutal effort to pacify and reintegrate Chechnya in 1999 and the early 2000s, Russian media followed the Kremlin in demonizing Russian Muslims’ foreign connections. This rhetoric was especially critical when such contacts drew young men to the teachings of Arab Salafis, who advocate a “return” to what they see as the more authentic ways of the early Islamic community. For the last decade, however, Putin has drawn a sharp contrast between Russia’s relations with Muslims, including Muslims who are citizens (and/or migrant residents) of Russia, and their treatment in the West.

A shift was apparent already in 2013, when Putin declared, “Russia is not only not interested in the splintering of the Muslim world, but, on the contrary, pursues a firm and consistent policy of strengthening its unity.”

As in earlier periods of history, Moscow has found allies in Muslim clerics who have sought to guide the religious lives of the faithful—and make themselves useful in the state’s campaign to utilize clerical networks to conduct diplomacy with Muslim-led governments.

Crucially, influential Islamic scholars in Russia have validated, before domestic and international audiences alike, the most consequential—and controversial—decisions of Putin’s rule to date, including the annexation of the Crimea, the intervention in Syria, and the invasion of Ukraine. While advancing the Kremlin’s policies at home and abroad, Russia’s state-backed Islamic institutions have also tried to direct the evolution of Russia’s Muslim communities and manage their selective integration with co-religionists elsewhere.

The fate of Palestine has grown in importance for Russia’s Muslims as they have gained greater access over the last three decades to the global conversations and exchanges that have sustained—and frequently fractured—a global community.

Official Islamic institutions have steadily charted a path that has integrated Palestine into avenues of religious and, importantly, political engagement. These avenues mostly align with state policy, even if the Makhachkala pogrom was a clear example of an overstepping of these boundaries. For instance, following the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Russia’s Muslims began celebrating Quds Day, an annual occasion inaugurated by the Iranian revolutionary Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini for the world’s Muslims to express solidarity with Palestinians.

In recent years, Quds Day has featured more prominently in the diplomatic activities of Muslim clerics in Russia. During a 2017 sermon at the central Moscow mosque attended by diplomats representing more than a dozen Muslim majority states including Palestine, Mufti Ravil Gainutdin, the head of one of Russia’s most powerful Islamic institutions, called for “Our prayers for the independence of Palestine and for this state to be recognized by the United Nations. And for Russia’s signficant role in the achievement of this.” He went on to state that, “The position of our state and the people of Russia have remained unchanged since the time of the Soviet Union: Palestine should be recognized by the international community as an independent state with its capital in Jerusalem.”

Figures such as Gainutdin have also marked Quds Day by meeting with Hamas representatives. At a 2022 gathering, the mufti explained the context for that year’s celebration: “For more than 30 years Quds Day has been commemorated within the walls of the Moscow Cathedral Mosque. On the last Friday of the month of Ramadan we spent this day with great sorrow against the backdrop of another aggression and an escalation of violence on the part of Israelis against Palestinians as well as violation of the sanctity of the al-Aqsa mosque and Dome of the Rock.”

State-backed clerics have utilized Quds Day and related occasions to publicize shared Palestinian sympathies and to bolster Russia’s reputation as a great power with a uniquely benevolent relationship with the world’s Muslims. In interactions with Islamic scholars and Muslim officials from Africa, the Middle East, and South and Southeast Asia, Russia’s Muslim leaders have cast Moscow as a principled counterweight to the United States, NATO, and their legacy of more than two decades of war waged in Muslim countries across the planet.

To be sure, this advocacy glosses over the Soviet legacy of atheism. It also ignores or distorts the history of the Moscow’s brutal wars in Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Syria from 1979 to the present. Nonetheless, this stance has gained traction in an era when the circulation of images of Muslim civilian victims of American violence, and of children in particular, have become a way of illustrating how power—and injustice—operate across the globe.

Palestine has emerged as the focus of concerns that at once connect Russia’s Muslims to their co-religionists globally—and that hold a mirror to all that is false, critics contend, in a world in which Washington unjustly wages war against Muslims everywhere, all while claiming to champion human rights, democracy, and a rules-based international order.

Since October 7, Muslim clerics have joined Russian officials in championing Russian mediation. In an October 17 interview, Gainutdin argued that Moscow could play a pivotal role in resolving the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, because “Russia, with its balanced policies could be useful in a peace settlement, especially given its enormous authority in the Islamic world.”

Even more significantly, Gainutdin and others have placed primary blame for the suffering of Palestinians on the U.S. Linking the war in Gaza to American policies elsewhere, including in Ukraine, the mufti has emphasized that Russians and Palestinians essentially share the same enemies. In this view, the war in Gaza is an extension of the West’s war in Ukraine:

What’s stopping the creation of a sovereign, independent Palestinian state? The Western world, the United States, and Israel who have not agreed to implement the U.N. resolutions on the creation of an independent Palestinian state … The Western world, which thinks that the war [in Ukraine] should continue to the last Ukrainian, has seen that Russia is strong, that it can’t be beaten down, that Russia is headed for victory. They have to save face and find an exit from Ukraine. It’s possible that, as a backer of Israel, they want to decide the Palestinian question with their own hands and, by so doing, offer everything to Israel, and not to Ukraine.

While predicting the collapse of American support for Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, the mufti insisted that “Only with recognition of the rights of Palestinians can peace be established in the land of Israel.”

A Leader for the World?

Nowhere has the adaptation of the Palestinian cause to reframe Muslim piety in Russia been been more striking than in Chechnya. This once restive republic in the North Caucasus has since 2007 become the personal fiefdom of Ramzan Kadyrov, the son of a religious cleric who during the war for Chechen independence shifted his allegiance from the Chechen rebels to the Kremlin. Kadyrov is a key figure in Russian national politics.

He demonstrates fidelity to Putin as a zealous Chechen patriot. Boasting ties to Mixed Martial Arts celebrity fighters from the North Caucasus, Kadyrov cultivates the image of a strong man in every sense of the word. He is also a Muslim traditionalist, a proud Russian nationalist, and fierce backer of the war in Ukraine. Crucially, he manages this territory for Moscow and his personal coterie through a ruthless network of security organs, mirroring and reinforcing Putin’s personal autocracy.

Kadyrov has also offered himself as an exemplary leader for Muslim men everywhere—even if he lacks clerical credentials. He has emerged as perhaps the most important voice agitating for a spiritual mobilization in Russia on behalf of Palestine.

Within two days of the Hamas attack, Kadyrov took to his Telegram channel to declare support for the Palestinians. He warned against bombing “civilians on the pretext of destroying fighters,” even offering Chechen troops as “peacekeeping forces.” On the 11th, he praised Putin’s comments affirming the importance of Palestine for the world’s Muslims and acknowleding that the “Palestinian problem” resides in the “heart of everyone who professes Islam.”

In the days that followed, Kadyrov emphasized a recurrent theme in his political rhetoric: nefarious forces were targeting Islam in Russia and across the globe. In this instance, he highlighted the case of Nikita Zhuravel’, a nineteen-year-old man from Volgograd who filmed himself burning the Quran near a mosque. Local authorities arrested Zhuravel’ for “offending the feelings” of Muslims—and in a bizarre twist to the case, transferred him to Chechnya for prosecution. This was clearly to allow Kadyrov the opportunity to publicize the case as part of a wider anti-Muslim conspiracy. Kadyrov accused Zhuravel’ of working for Ukainian intelligence with the aim of creating religious strife within Russian society.

When the defendant repented and asked permission to convert to Islam, Kadyrov rejected his offer as the work of “a true shaytan” (a “demon” or “evil spirit”). “We are aware of Western methods,” Kadyrov declared.

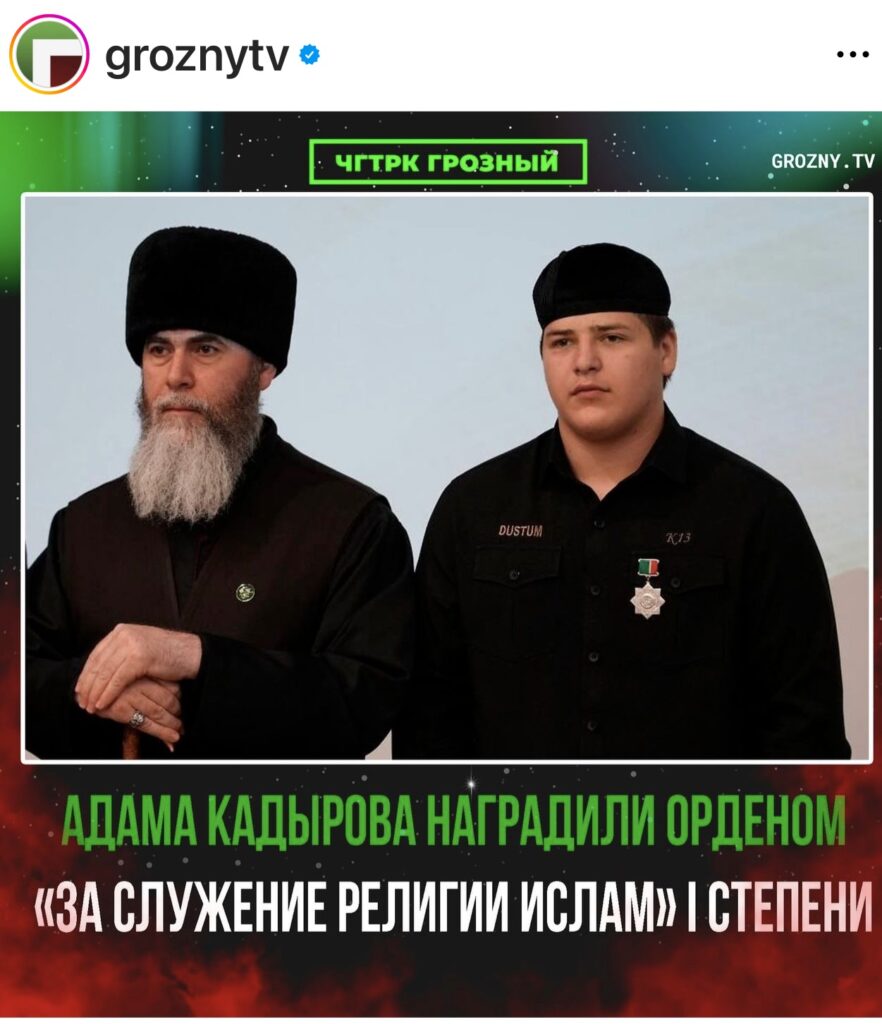

A few days later, Kadyrov’s Telegram channel circulated video footage of Kadyrov’s fifteen-year-old son Adam beating Zhuravel’ in prison, for which the young Kadyrov would soon be awarded a medal in a much publicized ceremony celebrating his service to religion and the nation.

All of this was mean to show that in the Russia of Putin and Kadyrov, Islam is protected by the state, while the West only displays its hypocrisy by carrying out the genocide of Palestinians.

Kadyrov issued calls for all Muslims in Chechnya to gather in mosques for evening prayers for Palestine and for the “special military operation” that Russian forces were waging in Ukraine. More and more of the world was united, Kadyrov asserted, in condemning “the open genocide of Muslim Palestinianians.” Its perpretataors had “turned nearly the whole world against themselves with the exception of the same criminals and hypocrites among Western states,” who, he added, “were exactly those who support the Satanists and Nazis in Ukraine.” At the same time, Kadyrov was careful to condemn the Makhachkala pogrom of October 29th, directing his co-religionists to devote themselves to prayer—and to do their part to ensure the defeat of this enemy in Ukraine. The faithful were in no doubt, Kadyrov emphasized, that God would punish these crimes in this life and the eternal one to follow.

Russia as the New Center of Global Islam?

The chilling numbers of killed—at least 17,000 civilian deaths in the two months that the IDF has laid siege to Gaza—and graphic images of dead children pulled from the rubble have turned global attention toward Palestine and Israel and away from Ukraine and Russia’s war crimes there. The Kremlin has clearly welcomed this shift—and has tried to navigate a path that would position Russia on the side of Palestinian allies. Russian spokesmen have called for a political process leading to a return to Israel’s 1967 borders. At the United Nations, Russia has backed a resolution for an “immediate, durable and sustained humanitarian truce leading to a cessation of hostilities.”

The Israeli war has, however, forced Moscow to reconcile competing impulses. Focused on winning his war in Ukraine, Putin has tried to avoid directly antagonizing the Israeli government, which has not joined in on sanctions imposed on Russia after its invasion of Ukraine. Moreover, as many commentators have noted, Russian and Israeli societies have been for decades interconnected in numerous ways. Attempts by Ukrainian President Zelensky to link the Ukrainian and Israeli wars in the international arena have complicated matters further, as have Putin’s own recent asides about Zelensky in which he casually used anti-Semitic language that had become taboo in public speech in recent years in Russia.

Most importantly, the Russian leader has not given oxygen to U.S. President Joe Biden’s opportunistic efforts to morph Hamas and Russia into a common enemy, alleging “the assault on Israel echoes nearly 20 months of war, tragedy, and brutality inflicted on the people of Ukraine,” adding “Hamas and Putin represent different threats, but they share this in common: They both want to completely annihilate a neighboring democracy — completely annihilate it.”

Despite such assertions from the White House, Israel’s mass killing of Palestinian civilians has strengthened Russia’s standing by presenting Moscow with an opportunity to chip away at its isolation and stand side by side with critics of U.S.-Israeli policies. The U.N. vote of October 26 was a telling snapshot of this shift: the only countries that sided with Israel and the U.S. were Austria, Croatia, Czechia, Fiji, Guatemala, Hungary, Micronesia, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Tonga, Marshall Islands, and Nauru. Although there were 45 abstentions, mostly by countries in Europe and East Asia, 120 countries, including Russia, China, and almost all Muslim-majority countries, voted for the resolution calling for a truce and cessation of hostilities.

And by highlighting the propagandistic rhetoric of American and Israeli spokespeople and the media that reproduce their justifications for the destruction of Gaza, the war has provided Russian authorities many more opportunities. They now claim the upper hand in moral terms by portraying—and condemning—a reality that conforms more closely to the what television audiences can see with their own eyes than that offered by Western officials and establishment media allied with them.

The war may also be narrowing the gap between the Putin government and public opinion in key areas of the Russian Federation at a moment when opinion is clearly divided about offering sons and husbands as cannon fodder for the war in Ukraine. Once again, Muslim clerics seem to be acting as intermediaries.

In a statement issued the day after the attack on the airport, Muslim clerics in the North Caucasus were quick to reaffirm their support for Palestine while reiterating their view that the United States and the West were to blame: “the main reason for this conflict is the lengthy stagnation in the process of arriving at a Middle Eastern settlement and in the destructive actions of the U.S.A. and a number of so-called Western states that constantly, baselessly, and even criminally block this process.”

In contrast, they pointed out, Russia has always stood for an independent Palestinian state that would live in peace with Israel and called for an end to the bloodshed. The recent “provocations” in Makhachkala, as well as in Cherkessk (where a group of mostly female protestors had demanded the expulsion of Jews), were the work of those who wanted to destroy interreligious harmony in the North Caucasus. Pursuing their own interests, these “destructive forces” were trying “to call Muslims to come out in the streets against all Jews, including those who have lived for centuries on our territory, Jews who are citizens of the Russian Federation, who have no connection to the genocide of Palestinians committed by Israel, the U.S.A. and their minions.” “Antisemitism,” they insisted, “has no place in the multinational North Caucasus.”

“We can’t let our enemies use us as an instrument in the incitement of interconfessional and international discord in our land. The Muslims of the North Caucasus, just as our religion commands, can’t be on the side of hatred and intolerance toward other peoples and religions and can’t give into false calls to violence.”

What is notable here, beyond the accusation of genocide perpetrated by Israelis, Americans, and their allies, is the explicit condemnation of anti-Semitism and its identification with Western conspirators.

In the North Caucasus, the pro-Palestinian activities of Muslim clerics, now extending from prayers and sermons to charity fundraising drives and the hosting of newly arrived Palestinian refugees, has yet another dimension. In agitating for Palestine, they are directing a reimagining of Muslim piety. But they also appear to be reacting to popular pressures from below and from abroad.

Some seem to be working to channel popular anger, heightened by the circulation of images of wounded and dead Palestinian children and of the mounds of rubble left by American bombs where apartment blocks once stood, into more acceptable forms of protest such as collective prayer and the collection of donations for Gaza. While asking for prayers for Palestine, Muslim leaders have cautioned that sinister forces seek to poison relations between different religious groups within Russia. (It’s important to note, too, that Russian security organs in Moscow and elsewhere had been placed on alert as early as October 19th in anticipation of possible protests following Palestinian solidarity marches across the Middle East and Europe.)

To complicate matters further, in the North Caucasus in particular, Muslims have access to rival perspectives in the form of exiles from Dagestan, Chechnya, and elsewhere who relay their sermons, legal opinions, and commentary from Turkey and various Arab countries via social media to eager audiences back home. Given geographic proximity and the persistence of Arabic-language networks of scholarship and pilgrimage, the North Caucasus has long been fertile ground for new ways of engaging with the Islamic tradition. Exiles from the region have circulated throughout the Middle East from the nineteenth century. Varieties of Salafism are both well-established and evolving, creating a dynamic and pluralistic landscape of competition and potential mobilization.

Recent waves of emigres have fled repression at the hands of Russian federal as well as local authorities such as Kadyrov and his allies. The Islamic State may have attracted as many as 7,000 recruits from the region.

Solidarity with Palestine is now part of this mix. Oppositional figures based based in Middle Eastern countries such as the dissident Islamic scholar Abdullakh Kostekskii (originally from Dagestan) have used Russian-language social media platforms to critique Muslim leaders and Russian politicians and to oppose Muslim participation in Russia’s war in Ukraine. In a recent video (apparently viewed more than a million times), Kostekskii harshly criticized the head of Dagestan for denigrating the Makhachkala airport attackers. At the same time, Kostekskii equated Israel’s attack on Gaza with that of Russia on Ukraine.

It is not clear how Muslim audiences in Russia are responding to such messages. It seems likely, however, that a shared position in support of Palestine has blunted some of the arguments made against Islamic authorities aligned with the Russian state.

In fact, the same young men consuming electronic sermons from abroad that have been warning them against joining the Russian military to fight in Ukraine seem to have been willing to act as they did in Makhachkala (and not against the military mobilization per se) both because they felt more passionately about the Palestine cause and, crucially, they may have thought the authorities were on their side.

Since Muslim clerics backed by the Russian state had been calling for support for Palestinians since the Israeli invasion of Gaza began, the attackers in Makhachkala may have assumed, in keeping with historical patterns that have marked pogroms in the past, that they enjoyed official approval. Muslim clerics in the region have had to navigate a crowded terrain of “experts” explaining Islam to an eager young audience watching events unfold in Israel/Palestine.

State-backed clerics have been compelled to stay attuned to critical views from abroad and to stay one step ahead of men with an agenda devoted to critiquing Russian rule in the Caucasus. For his part, Kadyrov has tried to defang the diaspora by claiming it as his own: in one of his recent Telegram messages, he praised a member of the Chechen diaspora in Jordan for supposedly joining the Palestinian “uprising.”

But it is is important to recall that Palestine is not a cause that appeals just to angry, radical young men in the North Caucasus. Amid an increasingly crowded Russian-language mediascape of Muslim legal experts, psychologists, theologians, even female Muslim “influencers” like Amina Hanum, who usually focuses on Muslim fashion trends, have used their platforms to frame the suffering of Palestinians as a pressing concern for all Muslims.

Depopulating Gaza, Reordering the Globe

The war in Gaza has elevated the profile and importance of Muslim clerical and temporal elites in Russia—and placed Moscow in an advantageous position to offer its leadership as a counterweight to a Washington much diminished by its positions in proxy wars in Israel/Palestine and Ukraine. Putin has skillfully activated diplomatic channels to solidify relationships based on a critique of American and Israeli policies.

Within a three-day period in early December alone, the Russian president, accompanied by Kadyrov, met with the leaders of the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia and hosted Iranian President Raisi in Moscow. Ostensibly focused primarily on resolving the Gaza crisis, these conversations will also affect a long list of political, financial, and military issues, including Russia’s capacity to influence oil and gas prices, work around economic sanctions, and import sophisticated weapons systems.

A direct consequence of Israel’s merciless campaign against Palestinians, this emergent constellation of forces around Russia (and across its domestic political landscape) reveals how far the Hamas attack and Israeli response have thrown global politics into confusion—just a few months after most of the American political establishment was certain that Moscow’s isolation and defeat were imminent—and that regions such as Chechnya could lead Russia’s inevitable “disintegration.”

Meanwhile, Russia is now aligned with publics across the globe who see the war as a devastating indictment of Washington’s “rules-based international order” and the notion that we can divide the world neatly into a struggle between “democracies versus autocrats.” The war against civilians, most of them children, in Gaza has had nothing to do with rules or democracy. In holding a mirror to violence shorn of all legitimacy, the genocide of Palestinians is hastening a reordering of global power and the consolidation of a post-American political moment.

The tragedy of the Palestinians has served as a catalyst for this realignment, but it has been long in the making. The post-9/11 wars and the ongoing intervention of American forces in clandestine theaters across the globe laid the foundations of a deep skepticism that have cut across the ostensible “democracy/autocracy” borders delineated by so many Western officials and their allied figures in the media and academia.

Joined by their allies in Europe, most American and Israeli politicians remain immune to moral arguments about Gaza’s destruction. From targeting civilian populations to rolling back international migration law, their nihilism may satisfy domestic electorates for now—but its long-term effect will be to discredit institutions and ideas devised in the wake of the Second World War to contain violence and protect civilians. Palestinians in Gaza are bearing this horrific burden now. But the wholesale abandonment of such principles will reverberate around the planet, ushering in an era of even greater chaos and suffering.

Robert D. Crews is Professor of History at Stanford University and author of For Prophet and Tsar: Islam and Empire in Russia and Central Asia.