Perceived White Loss Postpones Black Futures

“Most of the “brethren” think that education should equip them with the proper instruments of exploitation so that they can forever trample over the masses. Still others think that education should furnish them with noble ends rather than means to an end.”

Martin Luther King Jr., “The Purpose of Education,” January 1, 1947 to February 28, 1947

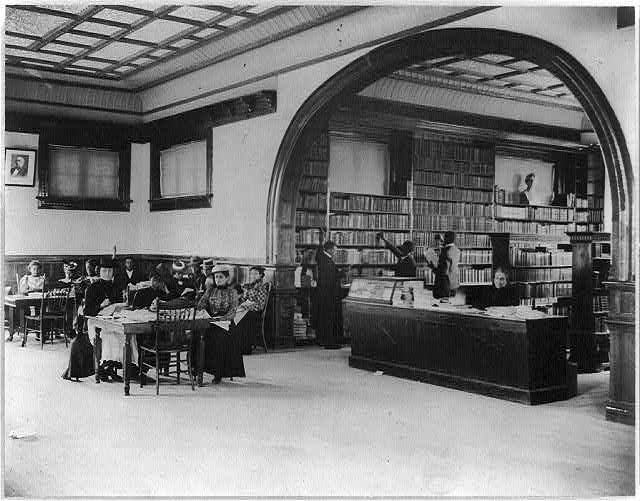

On June 29, 2023 Christine King Farris, the sister of Martin Luther King Jr., who taught at Spelman College for over 50 years, died. The news of Farris’ death at 95 years old was overshadowed by the decision on Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard with SFFA v. UNC by the Supreme Court. Born in 1928, Christine Farris was a member of the Silent generation; as a native of Georgia she grew up under Jim and Jane Crow laws, lived under legal segregation, and yet still believed in the power of an education. Her extended service as instructor and educator at Spelman College, a women’s historically Black college (HBCU) in Atlanta, GA, is our proof. As the older sister of a martyr for civil rights, she understood the role education played in forcefully requiring America to look at herself through the life and death of her younger brother. Her death on this day draws America back to her historic mirror; the reflection forces us to ask questions about the structure of our democracy and the meaning of education that allows us to maintain this democracy.

The Supreme Court has the country questioning the noble ends of higher education. Western education has long prided itself in teaching democracy, meritocracy, and egalitarianism and promoting the idea of social equality. Studies show that education is the most effective means to end generational poverty, which in turn allows for economic mobility and results in social capital.

The power of this narrative has spoken to Black women, making them the most educated group in America. Yet the Court’s decisions in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, Students for Fair Admissios v. UNC, and Biden v. Nebraska threaten the noble cause of education in the collegiate realm and enforce the idea that higher education is just a means to an end. Therefore, the decisions of the Court concerning college admissions and student loan forgiveness should be understood as a thinly veiled attempt to halt diversity efforts while solidifying debt amongst racially diverse communities.

The Founding of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court was established as a reaction to the actions initiated by the legislative and executive branches. Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist 78, “independence of the judges is equally requisite to guard the Constitution and the rights of individuals from the effects of those ill humors.” Although created to be reactionary in nature, politics and political ideology have always shaped the nature and thus the potential outcomes of the Court (Irons, 2006). Such thinking about the role and nature of a federalist government was tested in Marbury v Madison (1803). This case established judicial review, which has been a mainstay in the Court’s current functioning. Such authority allows the Court to determine the constitutionality of federal and state law and the constitutionality of executive orders. This authority was used in Biden v. Nebraska. The Biden Administration’s interpretation of the Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students Act of 2003 (HEROES Act) allowed for a student loan forgiveness program that would cancel about $430 billion in debt. The Court disagreed, stating that Biden’s interpretation resulted in an overreach affecting states’ higher education funding models. The Court believed its prevailing opinion aligned with the spirit that animated the founding of the Supreme Court.

However, the Court’s ability to define the parameters of the possible in places of ideological stalemate in our present moment is tenuous at best. Her noble aims concerning the question of race has America at an inflection point.

Today’s political climate is not one America has not seen before. Consequently, the Supreme Court is needed “to say what the law is” in this present moment (Irons, 2006). Yet moments are fleeting and fragile much like the rule of law, which is a hallmark of American democracy. It’s fragility is represented by Benjamin Franklin when approached by citizens asking about their government’s formation 20 years prior to Marbury v Madison. His response highlighted the fragility of the political system: “A republic, if you can keep it.” The balance struck in the Constitutional Convention was thus for the cohesion of the union in its historical political climate—a situation known to change requiring maintenance and vigilance from one generation to the next. Yet, the viability of the mechanism designed to ensure cohesion is in question today.

The history of the court shows that it has always struggled with the issue of race. Legal scholar Derrick Bell asserts that social change for minority groups occurs when their interests align with those of the majority, and such shared interests often lead to the creation of new laws and policies (Bell, 1980). Such a theoretical framework and its use in a collegiate environment is only a result of formal education, which is used in this instance to achieve a noble end: racial equality. The ability to theorize and best understand the nature of the law and the federal courts’ use of the law, leads us to the Court’s desire for the law to be color blind: to serve not as a racial ally but as a tool to justify cohesion of the union.

The Supreme Court’s Racial Pivot

The Supreme Court of the modern age has long operated on the premise that it could operate in a color blind manner. This phenomenon starts with Brown vs. Board of Education I (1954) and Brown v. Board of Education II (1955), which focused on the 14th Amendment of the Constitution (Maltz, 1998).

Such an approach seemed necessary when it supported the American foreign policy interests of democracy and equality on the heels of World War II. These historical cases allowed Blacks to demand equal treatment under the law, resetting how the Supreme Court previously dealt with questions of race.

Before these cases, states were not adhering to the spirit of the Constitutional amendments that codified the rights of Blacks, which were necessary due to historical concerns about the civil, social, and political rights of Blacks throughout the country after the Civil War (Nelson, 2022). Ratified between 1865 and 1870, Reconstruction Amendments included the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. These Amendments did three specific things: outlawed slavery unless convicted of a crime (13th Amendment); established citizenship for formally enslaved Africans (14th Amendment), and the right to vote for Black males (15th Amendment). Black women would have to wait for the 19th Amendment.

However, federal courts still provided legal justification for states not abiding by the terms of these amendments. Black codes, Jim and Jane Crow laws, and voting intimidation continued to place restrictions on Black civil, social, and political rights throughout the country.

On July 26, 1948 President Harry S. Truman desegregated the United States Armed Forces and the federal workforce with Executive Orders 9981 and 9980. Integration advanced the larger foreign policy interests of the United States. But, importantly, it also limited White political prowess. For Whites, policies aiming at integration delivered the first loss at the hand of the federal government since Reconstruction. Integration at this massive scale meant Blacks could achieve the same economic, social, and political standing as Whites, most of whom found this proposition untenable.

Brown vs. Board of Education challenged a precedent established by Plessy v. Ferguson (1895), the case that established the “separate yet equal doctrine.” Plessy had allowed for legal segregation establishing dejure racism, which inherently disadvantaged Blacks and subsequently provided social advantages for Whites. This social hierarchy was pervasive in the southern states as it cemented White political power. Thus, in defining the possible, the Court codified in Brown a permanent loss in the eyes of much of White America.

In elevating educational opportunities for Black people, this perceived loss of social standing prompted willful defiance. State governors refused to integrate public schools, which resulted in the deployment of the National Guard. The resulting confrontations around integration produced historical figures like the Little Rock 9, who integrated Little Rock Central High in 1957; Ruby Bridges, who integrated William Frantz Elementary School in in New Orleans in 1960; and James Meredith, who integrated the University of Mississippi in 1962. This integration promoted fear amongst Whites because the social standing established in Plessy v. Ferguson had offered blanket protection for White economic, social, and political power. With Brown, the Court’s role in maintaining the cohesion of the union shifted in that it partially withdrew backing for White superiority.

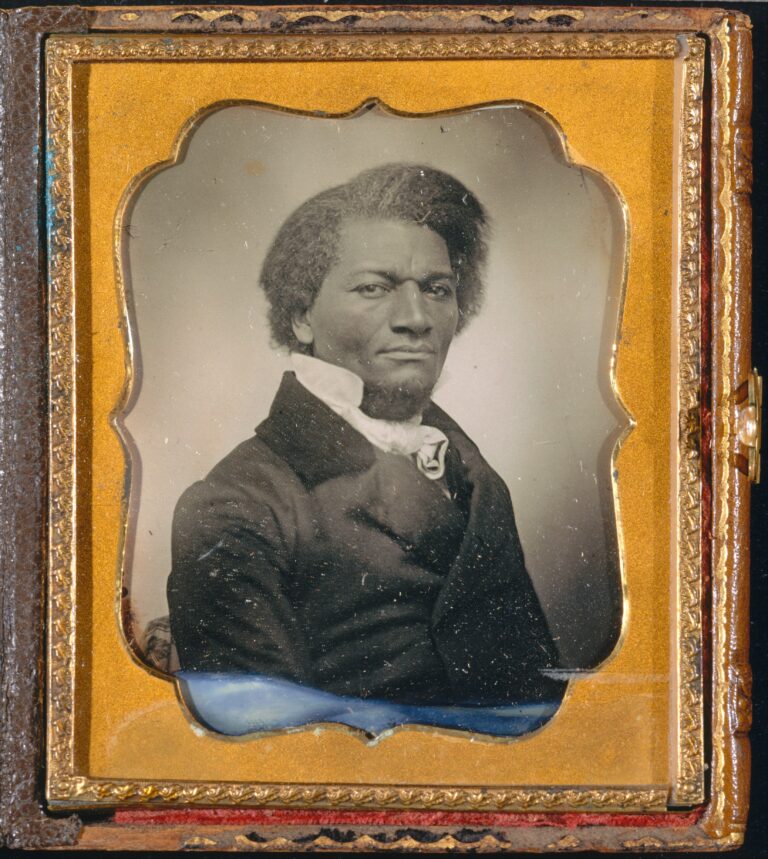

Brown v. Board cases acknowledged changes in American interests and the subsequent need for racial redress (Kluger, 2004). From the 1960s, such acknowledgement of inherent disadvantage for Blacks prompted colleges and universities to establish affirmative action programs across the country with a goal to increase racial diversity: especially via the admission of Black students. The influx of Black students fueled the perception among more and more Whites that they were losing out due to the rulings of the Court. As an index of the controversies surrounding affirmative action in higher education, the example of Barack Obama stands out. Of course, the 44th president graduated from not one but two Ivy League institutions: Columbia as a transfer student and Harvard Law.

Obama the Beneficiary Phenom

Perhaps no single figure encapsulates this anxiety about the loss of exclusivity in higher education more than President Barack Obama. Whatever the original intentions of U.S. policies aimed at integration, Obama’s story serves as a symbol of what a great education—and affirmative action—can provide. The election of Barack Obama as the first Black man to lead the United States has been reviewed, discussed, and analyzed by scholars, journalist and ordinary world citizens. Yet the common thread in a majority of these commentaries is the role of race. His presidency, in significant measure because of his rise through the educated halls afforded him through affirmative action, has become a symbol of loss.

Obama graduated from Columbia with a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science in 1983; only five years after the Supreme Court decided racial quotas were unconstitutional in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke. In 1990, Obama was elected as the first Black president of the Harvard Law Review.

A recent New York Times article reviewed Supreme Court clerkships and revealed a diploma from Harvard, Yale or Princeton results in a higher chance of placement in these coveted spots. Clerking for a Supreme Court justice requires some mastery of the Constitution. Although Obama did not clerk for the Supreme Court, his election amongst his peers trained to be constitutional experts speaks to his own mastery of the constitution. His superior acumen was noticed by his majority White peers at an institution only available to him through affirmative action.

Obama’s constitutional understanding and the federalist relationship established by the document was placed on full display during his presidency. He understood the country was not race blind and subsequently used race strategically to engage with and win the loyalty of voters, which resulted in two presidential terms (Price, 2016). His strategic use of race was tied to his wielding of the federalist relationship to target issues affecting Black communities in numerous and dramatic ways.

This is seen in his stance on marijuana in the Cole Memo, which stated that the Justice Department would not enforce federal marijuana prohibition in states that legalized marijuana in some form and “implemented strong and effective regulatory and enforcement systems to control the cultivation, distribution, sale, and possession of marijuana.” Obama’s use of the federalist structure in concert with state rights changed the narrative and consequences for Blacks who were far more likely to be criminalized in their relationship with the plant categorized as a drug.

His strategy to cement change through the use of the federalist structure is also seen in education. The Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act of 2009 (CARD Act) and the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (HCER Act) directly affected Blacks’ interaction with the fiduciary responsibility of education. The CARD Act is a consumer protection law enacted to protect consumers from unfair practices by credit card issuers. The provision, which does not allow young adults to open credit cards without a cosigner until the age of 21, directly impacted Black students on college campuses who were far more likely to have large credit card debt upon graduation. Furthermore, the HCER Act provides the bases for the student loan forgiveness plan recently struck down by the Supreme Court in Biden v. Nebraska.

The Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act ended the subsidies to private banks giving federally insured loans in higher education. Instead, these loans are now administered directly by the Department of Education. The Act also increased the Pell Grant scholarship award, which is the cornerstone of Blacks’ higher education. It provides more than $4 billion to African-American college students each year. The Act goes on to permanently change the structure allowing new borrowers who qualify to cap the amount they must spend on loan repayment each month to 10% of their discretionary income (instead of 15%). These changes disproportionately help Blacks as their typical household has 12.7% of the wealth of the typical White household.

Although bright and capable, Barack Obama’s trajectory, as the former leader of the free world, is at the center of the fear that has gripped the Western world. Many are asking this question in a variety of ways: what does racial diversity and unfettered access to legacy institutions mean for the current social and political order? The answer to this ultimate question causes the elites of Western societies to grapple with the idea of loss: real or perceived.

Such a loss is jarring for those who once exclusively decided the meaning of noble ends. This reorientation promotes fear for some and disillusionment for others. These emotions are at the heart of the cases recently decided on by the Court, which has now adjudicated the legalities of racism making race an elusive intangible. For all of the attention that the Supreme Court has devoted to these cases, our present political moment—and our understanding of what the law actually is—remains shrouded in fear of the unknown.

The Trump Era and the Federal Courts

The election of Donald Trump was a response by American Whites who believed they had lost the value of their Whiteness. This is seen in his campaign slogan “Make America Great Again,” a rejection of perceived racial progress coupled with resentment over access to elite education. A review of his campaign and subsequent nomination in the 2016 Republican primaries will show that he only gained a plurality. In a crowded political landscape, he rose the victor due to partisan cohesion around holding the power of the presidency and not due to ideological convergence. Yet the fear and the question of what has been actually lost galvanized a public with grievances about the future.

Subsequently, Whites went to the voting booth in 2016 willing to defend the social, political, and economic standing of their communities (Abramowitz & McCoy, 2018). Negative reactions within White communities to the potential acquisition of new power and or new status by Blacks prompted legislation and legal cases with high media visibility. This caused a media frenzy forcing the American populace to consume alternative facts and democratic backsliding, while normalizing bigoted political behavior. All of these forces ultimately upset the ideological balance of the Supreme Court.

With a shrinking political landscape and increased political polarization, the apolitical facade of the federal judiciary was upended. Its ostensible color blindness faded, driven by anxieties about racial progress and nervousness about conservatives’ ability to control the legislative and executive branches in the future. A 2021 New York Times piece shows that White college graduates are now a firmly Democratic bloc, and those without degrees, by contrast, have flocked to the Republican Party. Therefore political parity, or perhaps domination by the Republican Party, can only be achieved with the color blind doctrine that champions White supremacy within the federal judiciary.

In his four years, Trump appointed a total of 226 federal judges, 174 district judges and 54 appellate judges among them. The sheer number of judges is striking, especially when Obama only appointed 55 appellate judges in is eight years. Trump’s federal appointees have operated on extremely conservative ideologies about the rule and function of the federal court, which has eroded popular trust in the American judicial system. To make matters even more severe, more than a quarter of active federal judges are Trump appointees. Their life appointments mean that their color blind approach will result in ignoring a racial history that places us in our current political climate.

This Supreme Court mirrors this ideological reality. The presence of Trump’s conservative appointees Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett have been immediately felt in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, in concert with SFFA v. UNC, and Biden v. Nebraska. The concept of educational equality through affirmative action was deemed unconstitutional in cases involving two institutions with racialized histories connected to slavery. Access to a private education at the oldest higher education institution in the nation, Harvard, is reserved for those whose privilege allows them to attend. This sentiment is mirrored in that same decision concerning the oldest public university in the nation: the University of North Carolina. Access to elite White institutions has the potential to produce non-Whites with similar elite access. Non-Whites access to elite education has produced a subversion to White Supremacy. Non-Whites who are granted access to elite spaces often use this education to the more nobler end of racial equality.

Biden v. Nebraska pushes this denial of access and subsequent opportunity even further. A mapping of student loan debt by zip code in America was done by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth in 2016. The findings were clear; there was a strong relationship between a zip code’s minority population and its delinquency rate among minority student loan borrowers at both the city and national level. A more detailed look will show that the zip codes with the poorest populations are more likely to be Black and have high student loan delinquency rates. The Court’s majority opinion of presidential overreach in regards to student loan debt disproportionately hurts Blacks. The Constitutionality of the issue is wrapped inside the issue of judicial review but is implicitly aimed at trying to offset White loss and counter the progression of Blacks.

What Does the Future Hold?

There are many questions about the way forward with fear of racial rewind in a country whose achilles’ heel has always been the issue of race. Instead of conjecture, let’s focus on what we know about the nature of racism and its subsequent effects. Racial exclusion is based in the fear that equality disadvantages those who should be superior. The myth of White supremacy has licensed particular institutions, with the luxury of turning a blind eye to their parasitic pasts, with the ability to exploit the masses through the telling of their own story. This story must continually be debunked in historical institutions bold enough to tell the truth about the nature of color blindness. In an educational framework, Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) have been at the vanguard in pointing to the hard truths about the nature of racism and have actively worked against its advancement (Favors, 2019).

Policy proposed by the legislative branch and implemented by the executive branch is always subjected to the ideological whims of those in power. Anti-Black policies are a mainstay in an American polity that relies on the judiciary to prescribe what manner of color blindness will result in union cohesion. This is the ultimate function of the Supreme Court: only to serve as a racial ally in the interest of maintaining the union. Justices review the constitutionality of policies. Yet they are just one tool of exploitation, which continually perpetuates the myth of superiority. Such a pervasive narrative is all but guaranteed with the ideological imbalance of the federal courts. This is a direct result of White fragility, which requires maintaining a color blind doctrine to further White interests. The need to remain in power is fueled by the idea that racial equality could result in the oppression of Whites.

This is directly seen in the Court’s decision about affirmative action and student loan debt in relationship to Black women. Their intersections of race and gender drew them to education as their only chance at equality. This is best understood through misogynoir, a specific hatred, dislike, distrust, and prejudice directed toward Black women. Their educational status as a group serves as proof of the loss Whites feel at the hand of the Courts, which these decisions have targeted.

The education of a racially diverse public will continue in America. But the Court’s decisions lead us back to the question about the meaning of education. Is education an instrument for exploitation or the training to reach for noble ends? The Court’s decision has cemented the answer for our current political moment: if education is the instrument used to achieve noble ends, it means a narrow and expensive path for Blacks in America.

Dr. Sherice J. Nelson is an Assistant Professor at Southern University and A&M College.

References

Abramowitz, Alan, and Jennifer McCoy. “United States: Racial Resentment, Negative Partisanship, and Polarization in Trump’s America.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 681, no. 1 (2018): 137–56.

Bell, Derrick A. “Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma.” Harvard Law Review 93, no. 3 (1980): 518–33.

Favors, Jelani M. Shelter in a Time of Storm: How Black Colleges Fostered Generations of Leadership and Activism. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Eskridge, William N., and Sanford Levinson eds., Constitutional Stupidities, Constitutional Tragedies. NYU Press, 1998.

Irons, Peter. A People’s History of the Supreme Court: The Men and Women Whose Cases and Decisions Have Shaped our Constitution. New York: Penguin, 2006.

Kluger, Richard. Simple Justice: The Jistory of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality. New York: Vintage Books, 2004.

Nelson, Sherice Janaye. The Congressional Black Caucus: Fifty Years of Fighting for Equality. Bloomington, IN: Archway Publishing, 2022.

Price, Melanye T. The Race Whisperer: Barack Obama and the Political Uses of Race. New York: New York U.P., 2016.