Sonic Narratives of Resistance and Cultural Memory in Afghanistan

Despite severe restrictions and punishments, Afghanistan’s musical artists are emerging as some of the fiercest resisters against the Taliban.

It has been two years since the Taliban’s usurpation of power, and music has been among the first casualties of their systematic oppression. There has been an ongoing campaign of violence against musicians, musical instruments, and the public performance of music, forcing many to flee the country and live in exile. This follows a host of initiatives to restrict, suppress, and control nearly 40 million citizens resulting in conditions experts have condemned as ‘gender apartheid.’ Taliban decrees not only curb fundamental rights for all citizens, they also target various forms of cultural expression for destruction. The destinies of countless artists and musicians, within the country and in exile, represent the fragile threads of Afghanistan’s musical heritage. What comes to the fore is thus the urgency of cultural preservation despite attempts to erase or diminish the existence of musical sound and performance.

For the Taliban, music is deemed to be against public morality and contrary to the teachings of Islam. Since August 2021, they have reinstituted censorship of music and musicians, much as they had done between 1996 and 2001. This outlook, however, is disconnected from the country’s cultural heritage, breaking from “a rich intellectual tradition; from spiritual symphonies in poetry, music, art, and culture; and from a sensitivity to changes in society and the world” (Salim 2021). Despite restrictions and punishments, and stories of loss and destruction, musicians, poets, and artists from Afghanistan are some of the fiercest actors resisting the oppressive order. Not only do musicians and artists resist through the act of performing music and poetry, but in the content of their lyrics and their power to keep alive music rich in regional, historical, and folkloric significance. This defiance, resistance, and the reworking of cultural memory is what we center in this essay and what is too often lost in studies of the crisis in Afghanistan.

Communities that have disproportionately suffered from the Taliban have been particularly active in mounting musical resistance. Consider the music and poetry emerging from the women’s protest movement. One such group, Akhareen Mash’al (The Last Light), started performing protest songs in August 2021 that address the state of women in the country. Hazara musicians have utilized music and instrumentation as tactical media to escape state censorship (Karimi 2017); women from north and north-eastern Afghanistan use songs to share their stories of hardship, oppression, and resilience (Niroo 2022); and young people are turning to classical Persianate poets to cope with the current tyranny of the Taliban (Shahrani 2023). Meanwhile, outside the country, live performances from some of Afghanistan’s most famous musicians in the diaspora have dedicated concert tours to protest Taliban rule.

Resistance music can take a myriad forms, from rap, pop, folk music, to protest songs. It is a means of struggle against social and political oppression, which also rallies, inspires, and mobilizes its audience in the fight for social change. Over the course of the past two years, music, and poetry from the Persian-speaking regions of north and north-eastern Afghanistan, largely communities that identify as Tajik, has proliferated across social media platforms and has gained a wide listenership both within the country and among the global diasporas. It has also circulated among resisters (muqawumatgaran) who are currently on the battleground fighting against the Taliban in organized resistance groups, such as the National Resistance Front.

These songs distill how communities in Afghanistan establish their sense of belonging to the land, which is often defined through common cultural values and language. For both the performers and listeners, this music maps out a clear distinction between the local and the indigenous, and the external and imposed. It serves as a mode of authenticating the value of preserving the existing culture (indigenous and familiar) versus the imposition of foreign beliefs and ideologies (the alien, transplanted, and unfamiliar).

Resistance Music and Poetry in Persian Language and Literature

One of the most potent ways musicians and artists are resisting is with literature and language that resonates deeply within the rich tapestry of Afghanistan’s historical and cultural legacy. In a recent exploration of the language and literary dimensions of the resistance movement, Ahmad Rashid Salim highlights the resurgence of classical Persianate texts and thinkers, cast as “paragons of possibilities and purveyors of perennial wisdom” who align with the natural continuum of the identity (huwwiyat) of the people (2022).

However, beyond identity, this also encapsulates an intellectual reality connected to a deeper past where Persian literature served as a syncretic language that allowed for pluralism in society. In their deliberate deployment of this literary heritage today, notably through the prism of the Shahnamah, the revered Persian epic penned by Abul Qasim Ferdowsi, cultural producers including musicians and poets carve out a distinct space beyond the reach of Taliban ideology and, by extension, from ethno-linguistic hegemony in shaping the nation’s political and linguistic landscape. This engagement is not just an exercise in nostalgia; it is intended to galvanize and engender novel contributions to the realms of literature and language.

Take the viral video released in September 2021 as an example. With over 1 million views on YouTube, Tahir Shabab, sings the chorus “death to enemies” and “long live Afghanistan” in Persian and Pashto. Wearing military clothing, the video starts with him taking the flag of the fallen Republic and draping it over a stand. The song titled the Valley of Lions (Dara-ye shiran), Shabab connects the people, the resisters, and the nation to Rustam and Sohrab who are rooted in the land described as free (azad) and alive (zinda), with the enemies, referring to the Taliban, as foreign (begana/ajnabe).

Similarly, in local and regional music, in the spring of 2022, a video clip circulated across various social media platforms featuring Karim Andarabi singing while playing the ghichak, a traditional bowed string instrument currently outlawed by the Taliban regime. The video featured Andarabi, a musician as well as a resistance fighter, amid the picturesque mountains of Khair Dara in the Andarab region of Baghlan province, where a group of men had convened, engrossed by the enchanting melodies. Beside them lay Kalashnikovs and walkie-talkies, emblematic of their military affiliations within the ongoing conflict.

Come my countryman, let’s sit together

Among the gatherings of flowers, let’s sit together

The youth of this nation are buried or dead

Lets sit on one of their graves

May I never see you troubled, o homeland

May I never see the flowers of regret in your lap, o homeland

This striking tableau, coupled with the poignant lyrics and the evocative strains of the ghichak, struck a profound chord with numerous denizens of social media users. It rapidly achieved viral status. Viewers’ comments celebrated Andarabi’s performance as an affirmation of the power of traditional cultural forms to combat the Taliban: “at a time when music is forbidden, we consider music to be part of our culture and the trenches,” and “only in the anti-Taliban trenches is music permissible.”

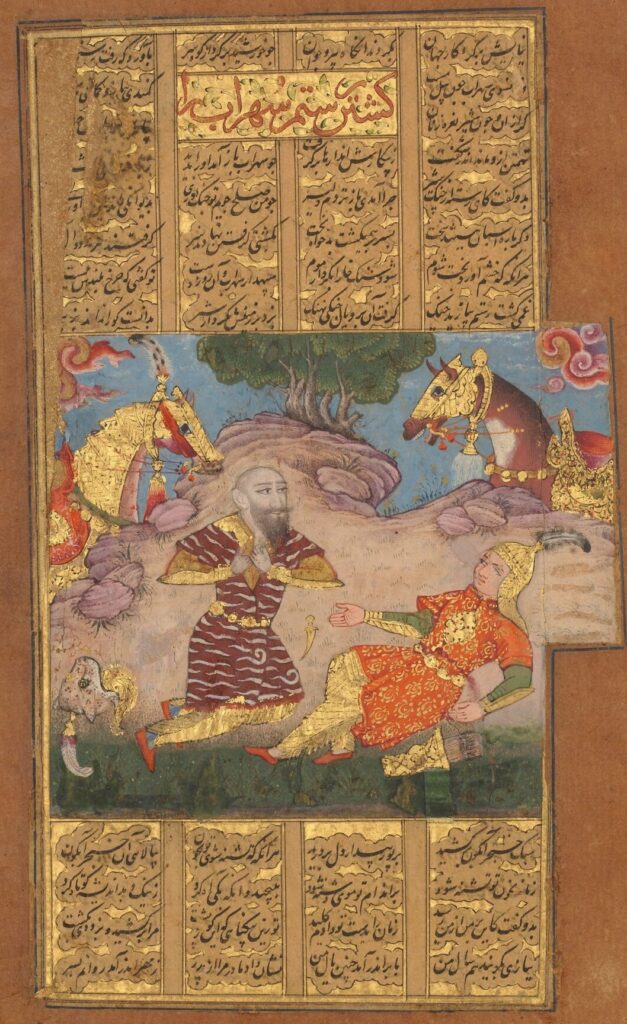

Among this gathering were individuals who had previously served as soldiers in the former Afghanistan National Defense and Security Forces. One notable figure among them was Haji Abdul Rahman, a resistance Commandant in the Andarab region, who also bears the distinction of being the father of the combatant, Mohammad Zaman, who was killed by the Taliban in Andarab in August 2022. Subsequent to the loss of his 23-year-old son, images of Haji Rahman, his countenance marked by profound solemnity, circulated widely across social media platforms. Many online users drew parallels between this image and the tragic narrative of Rustam and Sohrab, the iconic father-son duo immortalized in the Shahnamah (see Figure 1).

This evocative depiction resonated so profoundly within the ranks of resistance supporters that it was bestowed with the title of the ‘symbol of resistance’ against the Taliban. Notably, Ahmad Massoud, the leader of the National Resistance Front, prominently featured an illustration of this image on his Twitter profile (see Figure 2). This coupling of the aural (song) with the visual (images of martyrs) serves as a dual-pronged mechanism not only for disseminating multimedia content effectively across social media but also for enshrining the events and individuals affiliated with the resistance movement. In essence, the music’s political effect is co-produced by the visual aides and contributes to distill an overarching message and meaning.

Another example of this can be found in the song “Gulolah ha”: Panjshir wa Andarab (Bullets: Panjshir and Andarab), performed by vocalist Shafaq Siaposh and released during the summer of 2022. The composition commences with a voice message from Haji Rahman recounting the sacrifice of his son and Commandant Shahwali along with fellow resistance fighters who confronted the Taliban for a span of one day and one night. The video then adeptly integrates an illustrative depiction of Rustam and Sohrab, invoking familiar figures from classical Persian literature to symbolize concepts of justice, duty, and epic tragedy. These songs serve as manifestations of this creative and generative process. Specifically, Karim Andarabi’s aforementioned musical composition, accompanied by his virtuoso performance on the ghichak, artfully merges a well-known poem entitled “watan” with his interpretation. Within the lyrical tapestry of this composition, themes of martyrdom, homeland, freedom, and the prevailing climate of violence in the nation converge, resonating with, and encapsulating, the collective sentiments, and grievances of many.

Karim Andarabi’s melodic rendition in the featured clip also evokes memories of Fawad Andarabi, a local musician from Baghlan, who also played the ghichak and met a tragic end when he was abducted and fatally shot by the Taliban in late August 2021. In both instances, the poetic and performative elements of these songs symbolize acts of resistance against the backdrop of political violence, displacement, and dispossession. Furthermore, they stand as staunch expressions of solidarity with the local resistance fighters, who, in turn, assert their belonging to the land and homeland through sharing and disseminating this audiovisual material. Collectively, this fusion of music and poetry serves as a poignant embodiment of what Zuzanna Olszewska describes as the “many-layered histories and memories of past events, whether atrocities or moments of glory, and in some cases intertextual allusions to classical poetry and other literary or historical works” (Olszewska 2023).

Transitioning from our exploration of these evocative songs and their roles in representing resistance, we pivot to a poignant episode from Spring 2023 when the Taliban killed the young Commandant Akmal Amir, a former Commander of the Republic’s Special Forces. In response, the prolific Herati poet, Shiba Rahimi, who routinely disseminates her poetry on social media, shared a poem with her large Facebook audience. Accompanied by images of Commandant Amir engaged in combat, Rahimi’s words encapsulated the sentiments of thousands of social media users who expressed grief over his death.

This face has been taken over by the glory of martyrdom

Look at its glory in his stature

The tall Hindu Kush kisses your feet

Surely the enemy has taken fright by your name

From the pure soil of the homeland with much pain and regret

The dark soil has been united with your beauty

The heart is set on fire and what smoke trails behind

As this is how your absence has been created

Yes, o sleeping guerilla in blood because of the homeland

Know that the homeland has taken glory in your blood

In this poetic composition, Rahimi pays tribute to Commandant Amir’s resolute commitment on behalf of the people, venerating his unwavering loyalty to the homeland, even in his demise through combat. Analogous to other forms of resistance music and poetry, this literary expression situates the individual within a framework of communal mourning and collective struggle, aimed at ending the dominion of the adversary (ishghalgar) and promoting self-determination. Rahimi’s characterization of Amir as embodying the “glory of martyrdom” in battle signifies a sacrifice encompassing multiple facets, such as devotion to a divine cause, the pursuit of honor, the defense of one’s homeland, and more. Unlike the martyrdom proclaimed by the Taliban with immediate compulsion with death or dying through suicide bombing, martyrdom here puts more emphasis on struggling to seek victory and doing everything to avoid death, but death as an end to this struggle would be an ultimate prize (Seyed-Gohrab 2021). For these communities, martyrdom is deeply connected to mystical poetry and Sufism in achieving self-annihilation to gain unity with the beloved (Seyed-Gohrab 2021). Part commemorative, part rallying call, such poetry and song express the will of the collective to survive and reiterate its values.

The Past and the Present

A cadre of emerging young artists, such as Sufi Shaheen, Sufi Shoaib, Mullah Waheed, Shakib Azizi, Pahlawan Rafi, to name a few, are actively engaged in the creation of resistance music. These artists contribute to the musical landscape by composing and distributing their music through popular social platforms such as YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram. This contemporary media environment represents a transformative paradigm, as it has introduced innovative means for both the production and consumption of music. Notably, platforms like YouTube have dismantled traditional constraints of time and space, affording unprecedented opportunities for songs to achieve instantaneous global dissemination upon their release.

One of the most popular voices of this emerging genre of post-2021 resistance music is Sufi Shoaib. A 28-year-old from Panjshir province who has lived in exile since 2021, Sufi Shoaib tells us that he adopted Sufi as part of his name from Sufi Majid Panjshiri, the popular local artist of the anti-Soviet resistance in northern Afghanistan. He recalls listening to his music as a child when the Taliban had taken power in the mid-1990s, and his home province was under the control of the internationally recognized government at the time. Sufi Majid’s songs were resurrected from the time of the Soviet-Afghan war, to encourage the resistance against the Taliban in the 1990s. “I loved revolutionary poetry, and those that are for the freedom of the country,” said Sufi Shoaib. Inspired by Sufi Majid’s style and substance, Sufi Shoaib reflects these thematic and sonic influences in his music that serves as a response to the current Taliban occupation and, in his words, “capture the pain of millions.” Aside from a mass audience of primarily Persian speakers within and beyond Afghanistan, Sufi Shoaib counts as his audience resistance fighters with whom he is in direct contact, including the famed Commandant Khalid Amiri.

When asked about the themes of his songs, and why he sings resistance music, Sufi Shoaib spoke of “love, and especially love for God, and those who are lovers of freedom” as his main motivations. His primary inspiration for the lyrics of his ballads come from the writings of late master poets who are pivotal figures in the Sufi traditions of Afghanistan such as Abdul-Qadir Bidel and Haidari Wujudi, as well as the contemporary poet, Najib Barwar. During an event to commemorate the life and death of the late resistance commander, Ahmad Shah Massoud and other martyrs of Afghanistan in September of 2022, Sufi Shoaib performed an acapella song with the chorus that repeats, “may the soldiers of the resistance be victorious and hold their heads high.”

In the sway of the wind, the forces of the resistance

Victorious and proud, the forces of the resistance

Freedom is the lesson and message of the resistance

Bringing life to the country is the motto of resistance

This uprising is against foreigners

My lord, give durability to the resistance

Lovers of freedom do not submit to oppression

They sacrifice their lives, not the honor of the country

These songs, which are commonly performed in local spaces where resistance is both memorialized and encouraged, employ alternative media (in this case YouTube, Facebook, Instagram) to get their message across without falling prey to state censorship or the gatekeeping practices of Taliban establishment media. It is this tactical media that deploys a certain do-it-yourself activism made possible by digital technology and the internet (Karimi 2017). Moreover, digital technologies have helped communities in flux (whether recent migrants or refugees) stay connected with their origins. Websites such as YouTube have lifted barriers of time and space and have given opportunities for resistance music to circulate within minutes. In the past, the audiocassette served as the main medium to distribute these songs (Massoumi 2022). Today YouTube is the global medium for many marginalized music makers who are invested in disseminating their music and digitally preserving their cultural heritage.

Similar to Sufi Shoaib, Pahlawan Rafi, a noted folk musician and vocalist from the Shamali Plains of Afghanistan, recorded a song in the Spring of 2022:

Begin the cry of takbir (repetition of ‘God is Great’) with a beautiful voice

Be a revolutionary, take up arms and fight the enemy

Living in captivity is not our principle.

Put an end to the shackles, restriction, and shame

There is no God but God

The chorus of the song echoes the Muslim shahada (profession of faith), “there is no God but God,” and it is also a nod to an earlier version of the same song produced three decades ago in the 1980s by Sufi Majid Panjsheri. At that time, this song served as a rallying call for the opposition against Soviet forces and its client regime in Kabul. In 2022, it served as an anti-Taliban anthem. In both iterations of the song, Islam remains a central theme with an emphasis on distinguishing it from foreign interpretations, be it from the Soviets of the past, or the Taliban of today. This song then becomes a living, performative archive that captures the sentiments and sounds of past conflicts and feeds into the battles of the current moment.

The relationship between religion and music has often been complementary in musical performances. Lorraine Sakata, an ethnomusicologist who has written extensively on musical practices in Afghanistan and other Muslim societies, concludes that “Islam is so integral to the lives of the Afghans that virtually every activity is tinged with religious meaning; musical activity provides no exceptions” (Sakata 1986). While her study of Afghanistan’s music dates to fieldwork conducted in the 1960s and 1970s, the association between Islam and music has remained over time. When Pahlawan Rafi melodiously utters “there is no God but God” he is seeking divine protection from tyranny while also blessing the efforts of the ‘revolutionaries’ who will risk their lives to defeat oppression. The added layer of meaning is the certainty that the Taliban do not represent an accurate or sound understanding of Islam, so much so that the invocation of the sacred shahada – that when recited with conviction asserts one as a Muslim – is used to divinely announce that distinction between the faithful believers of Islam and those who misrepresent it.

Conclusion

In Afghanistan, music and poetry serve as windows into a world where despite ongoing oppression, one can understand the intricate ways individuals navigate their grievances, create solidarity against a common adversary, and foster collective resistance. In this brief essay, we have provided a sampling of resistance music and how this genre has taken flight in the current moment where the very act of musical performance is forbidden and subject to punitive measures. Taking risk to create music and circulate it widely throughout the world, these examples showcase how these artists are invested in preserving traditional cultural practices of reciting and singing classical Persian poetry while also imbuing it with newfound significance.

Although resistance music and poetry have historical precedence in Afghanistan, especially in the resistance poetry of the 1980s in Afghanistan, today’s artistic output represents more than a revival or repurposing of earlier music and poetry. Instead, it signifies the genesis of a distinct musical genre that has a much broader reach through the usage of social media. The new wave of mass internal and external migration of the people of Afghanistan has meant that the production of this audiovisual and textual material connects people to each other across borders, as well as within them. Resistance music fundamentally mirrors a society entangled in conflict, yearning for the cultivation of its distinct cultural identity and development. This multifaceted artistic expression serves as a formidable instrument, enabling communities to inspire, resist, and preserve.

Munazza Ebtikar is a doctoral student at St. John’s College, University of Oxford, where she is completing her thesis on war and memory in Afghanistan.

Dr. Mejgan Massoumi is a lecturer and fellow in the Civic, Liberal, and Global Education Program at Stanford University.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the American Institute for Afghanistan Studies for providing a seed grant for this project and Wali Ahmadi and Nazif Shahrani for their support of this research. We also thank Omar Sadr for his insights. We especially thank Robert Crews for his insightful suggestions, meticulous editorial guidance, and encouragement throughout.

Works Cited

Karimi, Ali. (2017). “Medium of the Oppressed: Folk Music, Forced Migration, and Tactical Media,” in Communication, Culture and Critique, Vol. 10, Issue 4, pgs. 729-745.

Wolayat Tabasum Niroo. (2021). “Nurturing Masculinity, Resisting Patriarchy: An Ethnographic Account of Four Women’s Folk Songs from Northeastern Afghanistan.” Afghanistan 4 (October): pgs. 170–92.

Salim, Ahmad Rashid. (2022). “Tongue-Tied and Heart-Bound: the Lines of Language, Literature, and Religion in the Resistance,” Afghanistan in Global Perspective Symposium presented by the Center for Global Studies, Penn State University.

Salim, Ahmad Rashid. (2021). “The Taliban vs. Global Islam: Politics, Power, and the Public in Afghanistan,” in Islam, Politics, and the Future of Afghanistan, Georgetown University Berkley Forum, Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs.

Massoumi, Mejgan. (2022) “Soundwaves of Dissent: Resistance Through Persianate Cultural Production in Afghanistan,” Iranian Studies, 55, pgs. 697-718.

Olszewska, Zuzanna. (2023) “If we do not write poetry, we will die: Afghan Diasporic Social Media Poetry for the Fall of Kabul.” The Routledge Handbook of Refugee Narratives, pgs. 140–152, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003131458-15.

Sakata, Hiromi Lorraine. (1986). “The Complementary Opposition of Music and Religion in Afghanistan.” The World of Music 28, no. 3: 33–41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43561103.

Seyed-Gohrab, Ali A. (2021). Martyrdom, Mysticism and Dissent the Poetry of the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988). De Gruyter.

Shahrani, M. Nazif. (2023). “Passive politics and poetics of spiritual resistance in Taliban Afghanistan.” Üsküdar Üniversitesi Tasavvuf Araştırmaları Enstitüsü Dergisi, pgs. 137–152, https://doi.org/10.32739/ustad.2023.3.44.