The Collective Punishment of Palestinian Refugees Continues

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) recently ruled that it would not throw out South Africa’s case accusing Israel of genocide. It imposed provisional measures on Israel to ensure that it doesn’t commit genocide and allows humanitarian aid to Gaza. Israel called the ICJ antisemitic. Shortly after that, Israel alleged that 12 workers from the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) were complicit in the October 7 Hamas attacks in Israel. Israel’s western backers heard the call to action. Major powers (including the U.S., UK, Canada, Germany, Italy, and Finland), all “appalled,” have decided to freeze funding to UNRWA pending further investigation of the allegations. All expressed disappointment with the ICJ ruling, registering “serious reservations” about the Hague court’s supposed errors of judgment.

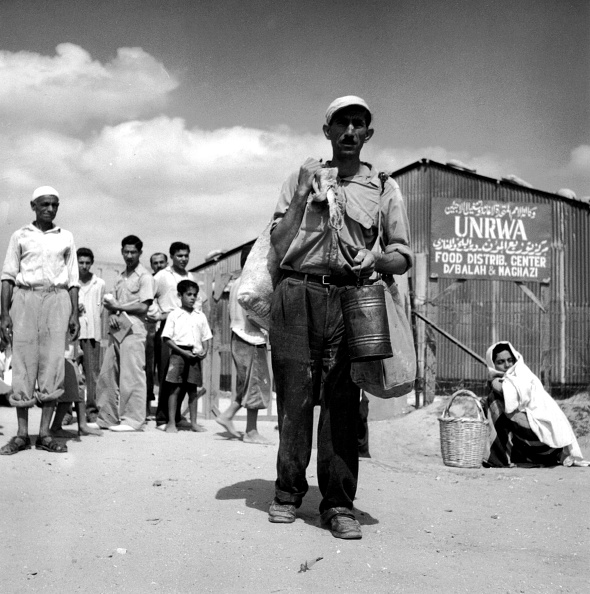

UNRWA is the agency solely responsible for Palestinian refugees. It provides and administers protection and services, such as health care, food, and education. Even with the now suspended funding, UNRWA says it can provide neither international protection nor services in Gaza. 85% of Gaza’s population of around two million is internally displaced as a result of the unrelentless Israeli shelling, murder of civilians, and mass-destruction of civilian buildings following October 7.

Israel has ordained that even tent poles and insulin pens can be used for military purposes. Israeli authorities have been prohibiting their entry into the Gaza strip and destroying them within the strip. However, within the logic of genocidal siege, some things are allowed, and so Israel graces Gaza with the continued flow of plastic body bags, which toddlers have been using as winter jackets. These children, and these are our children, have been surreally forced to clothe their play, their laughs, their words, the present and future of their precious lives in this cheap garment of death. Welcome to the world of Israeli necropolitics for minors.

This, apparently, is not “appalling” to Washington and Berlin. This is clothed in the language of horrific silence or a sociopathic “neutral” moral terminology—a terminology cast in neutral white, like the body bags.

UNRWA chief Philippe Lazzarini and UN head Antonio Guterres have rightly called the suspension of aid collective punishment of the Palestinians. Suspending the only source of vital humanitarian assistance to Gaza based on thus far unproven allegations, issued by a state whose key political and military leaders repeatedly show and act on genocidal intent, sends a message to the world: here we are beyond good and evil, beyond international law, here we allow, as we always have, an exception, here body bags are glossy winter coats that won’t keep you warm.

As morally twisted as it is, this specific form of collective punishment doesn’t mark a fundamental shift in the role of Palestinians in the politics of refugeehood. Palestinians have always occupied an anomalous position in the modern refugee regime. Bizarrely, Palestinians are unpersecuted according to the very definition of Palestinian refugee, with no right to return, trapped and unprotected under an occupation, and perpetually vulnerable to the whims of Israel and its backers in the U.S. and EU.

Palestinians are trapped by a special and bizarre refugee category

Around 5.9 million Palestinians are refugees today, following the 1948 proclamation of the State of Israel—including the descendants of those 750,000 who were forced to flee in 1948, according to the UN. The vast majority of the 2.2 million living in Gaza are already refugees from towns and villages now in Israel and in the West Bank.

Jordan hosts the most Palestinian refugees outside of Palestine, 2.4 million to be more precise (three quarters of them are Jordanian citizens). Since the war in Syria, additional tens of thousands of Palestinians have sought safety in the Jordanian camps. Gazans in Jordan, however, are barred from citizenship and rely on UNRWA for assistance. The 489,000 Palestinian refugees who live in Lebanon have no path to Lebanese citizenship. Around half live in camps and receive assistance from UNRWA. Many Palestinians in Lebanon lived in poverty even before the recent deep economic and political crisis struck the country, but since then, a staggering 80 percent are estimated to live below the national poverty line.

Legally speaking, what kind of refugee are Palestinians in Palestine and these neighboring countries? A unique one, with its own Kafkaesque definition. The UN defines Palestinian refugees as “persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict.”

The definition includes, to the chagrin of Israel, the direct descendants of the 1948 refugees, which is why Israel has called for the dissolution of UNRWA for many years. Israel has accused UNRWA of inciting “anti-Israel hatred,” allegedly allowing Hamas to operate tunnels under its buildings, and hindering a “solution” to the “refugee problem” by insisting on the right of return—claims rebutted as preposterous by UNRWA and external observers.

The UNRWA definition stands in stark contrast to the 1951 Refugee Convention, which defines a refugee as a person “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of [their] nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail [themself] of the protection of that country.”

Most notably, the UNRWA definition of Palestinian refugee does not include an element of persecution or persecutor, in any sense of that term. This is an absence, a silence, that speaks volumes. Palestinian refugees are thereby normally excluded from the Convention—decontextualized out of politics and out of the intentional structure of discrimination and violence that ensnares them.

The other noteworthy aspect: while the UNHCR, which oversees refugees under the 1951 Convention, works to provide international protection and a durable solution to refugees, including permanent resettlement to host countries and repatriation to the home country where possible, the UNRWA is strictly limited to providing social services, which effectively means acting like an agency for social work, employment, health, food, and education.

The international refugee regime uniquely treats Palestinians as if no actor is responsible for their displacement

The UNRWA definition follows, unsurprisingly, the politics of the powers that created it, not least UNRWA’s biggest donor, the U.S. These powers, Israel, and Israel’s other state supporters, have, since 1948, kept repeating two statements: 1) Palestinians are refugees without persecutors. 2) The Palestinians themselves are responsible for their victimhood. Meaning: Israel and its allies have nothing to do with it, and thus bear no culpability for the plight of the Palestinians.

A 1948 memo from the newly formed Israeli state to the U.S. government is crystal clear: “The government of Israel must disclaim any responsibility for the creation of this problem. The charge that these Arabs were forcibly driven out by Israeli authorities is wholly false; on the contrary, everything possible was done to prevent the exodus.”

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz must have read the memo and applied what he learned today, going by one of his recent statements: “But there is no doubt that Palestinians in need depend on our help. They too are victims of Hamas and its oppression.”

On the U.S. side, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, not to be outdone in showing blind support for Israel, was “deeply sorry” about the clearly targeted murder of civilian Hamza Dahdouh, son of Al Jazeera Gaza bureau chief Wael Dahdouh, yet didn’t hold the Israeli military accountable in any sense. He then went on to say: “Hamas could have ended this on October 8th by not hiding behind civilians, by putting down its weapons, by surrendering, by releasing the hostages.”

But the prize for best elision of persecution goes to Israeli government advisor Mark Regev, for when asked by journalist Mehdi Hassan about the tens of thousands of children murdered in Gaza, he said: “First of all, you don’t know how those people died, those children.” Winter coats. They died in their white plastic winter coats. Regev may as well have said that.

Isn’t this the language of body bags? Our political leaders are, with a mix of offhandedness and ice-cold calculation, wrapping any public speech that dares blast the truth (that there is a genocide unfolding in real-time with an abundance of evidence) in that crackling white plastic pouch and telling us to zip it up, or they’ll zip it up for us—how many have been suspended on social media? How many lost their jobs? How many have been arrested? Too many. They’re trying hard to kill our ability to speak the truth about the collective punishment. Welcome to the world of western necropolitics for moral language.

Palestinian refugees are physically trapped

Palestinians, in particular Gazans, are effectively banned from leaving Gaza and the West Bank without permission from Israeli authorities. Do Gazans even want to leave? From anecdotal evidence, we know that some do, others don’t, while some worry that if they do leave, they’d be permanently exiled with no chance of returning and exercising their right to political self-determination.

Those who do want to leave face impossible barriers. There are reports of Gazans having to pay bribes to “brokers” of up to $10,000 to help them exit the territory through Egypt, which keeps its one and only border crossing point at Rafah mostly closed. U.S. Citizens trying to leave Gaza are apparently being ghosted by the U.S. Embassy in Jerusalem.

Western and Arab resettlement states are reluctant to grant protection to Palestinians

We can now begin to understand why only 2,000 Palestinians have been resettled to the U.S. in the past 20 years. In 2023 a mere six Palestinians were granted asylum in the U.S., two in Sweden (which is fewer than the number of U.S. Citizens granted asylum in Sweden), 720 in Belgium in 2022. You get the picture. Small numbers.

Couldn’t Gazans be airlifted and paroled in to the U.S. and other countries, like Ukrainians and Afghans, and given some form of, at the very least, special temporary protection?

Yes, in theory, but Washington has said that it has no intention of pursuing this option. But even if it did, I wonder if it wouldn’t end up similar to the temporary visa scheme Canada has created for Palestinians with Canadian extended family members or private sponsors, a “humanitarian pathway” for up to 1,000 people for one year, “whichever comes first.” Note that over 200,000 Ukrainians were welcomed in Canada after the February 2022 Russian invasion.

How can you get such a visa? You have to show your detailed employment history since the age of 16, links to all social media accounts and those of your in-laws, and details about any scars or injuries you have, how you sustained them, and if they need medical care. Canadian attorneys have explained that such excessively detailed information isn’t typically required and seems cruel in its invasiveness.

What about the neighboring Arab states? Couldn’t Palestinians flee there? No. Egypt and Jordan have explicitly said that they will not accept large numbers of Palestinians out of lack of reception capacity, “security” concerns, and political positions, chiefly that it would undermine a two-state solution and bar Palestinians from returning to their homeland.

What comes next? How about: what came before?

I’ve heard several major newspaper editors, pundits, and Israeli government spokespeople say that there can be no context for October 7. And UNRWA, with the most recent allegations, is now part of October 7.

Israel and its allies want to gut context out of public and legal discourse for obvious reasons. Without context, they can justify any atrocity and still remain a victim only engaging in self-defense against “human animals,” “two million Nazis,” “genocidal Hamas.”

“What can we say to make it look like Israel is not committing war crimes?” Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte asked his staffers. I keep coming back to the body bags, and the kids, and the adults. I hear Rutte think, “could we say we’ve been sending those thin winter coats to the children?” By cutting aid to UNRWA, western countries have found yet another way to participate in the genocide unfolding before our eyes.

And of course, that’s precisely why context needs to prevail. Israel’s genocidal campaign following October 7, and its allegations against UNRWA, fit a pattern that’s over 80 years old. A crucial part of that context is the long history of legal, symbolic, and physical collective punishment of Palestinians sketched here imperfectly, but described in superb detail elsewhere, by the likes of Edward Said, Hannah Arendt, Ilan Pappe, Gideon Levy, Fady Joudah, Hosam Maarouf, and so many others.

What can we do to show that Israel is committing a genocide and get our leaders to act on it? We can join and support an already broad movement that’s demanding an end to the genocide, an end to the illegal occupation and settlements, an end to the collective punishment of Palestinians and Palestinian refugees, and a fully free Palestinian state that somehow (as hard as that is to imagine now) co-exists with Israel.

This can take many forms: countering decontextualized propaganda with contextualized truth, sending money for desperately needed humanitarian assistance, supporting South Africa’s case in the ICJ, exerting massive political pressure on our government officials, protesting on the streets, helping Palestinians who are trying to get to a safe country, speaking up in public, in the media, on social media, and supporting political parties that take a clear stance on this issue.

I just know we can’t stay silent. This concerns all of us.