Why HBCUs Matter in the Twenty-First Century

Dear Eva J. and Raila K.,

As I sat down at our dining room table during the summer of 2023–one of the hottest, if not the hottest, summers recorded–to begin writing this, my mind drifted back to the days when I was your age, I was born in Cairo, Georgia, and raised in the Sixteens, a rural southwest Georgia farming community, home to both black and white independent farmers and small factory workers. I recall fondly the days of running up and down the red clay roads from our house to our cousin’s home and spending the better part of a day playing football on Uncle Roosevelt’s well-manicured centipede grass until sundown. Shortly after 6 p.m., my cousins and I could hear cars three miles away as they turned off the highway onto the long, winding dirt road that eventually intersected into Ellis Lane. Nearly eight minutes later, we would see a small four-door white Toyota Corolla–now painted with red dust from the road–making a left turn onto Ellis Lane. A blow of the horn signaled it was time for me to sprint the nearly five hundred yards back home to ensure I made it there before the driver fully disembarked from their car.

Emerging from this compact vehicle was my mother, the person you are partially named for, Eva J.–in her early 30s, tall, slender, and with a deep brown complexion. I was always in awe of my mother because when she left for work every morning, my sister, your aunt, and I would still be asleep, and she never returned home before 6 p.m. Nonetheless, she always returned home adorned in a beautiful dress, gold earrings, neckless, and rings. In my mind, she smelled like what movie stars must have smelt like–the finest of fragrances–even after a long day of work. After exiting her car, she would swiftly walk into our house, take her work clothes off, slide into a nightgown, and begin cooking for her family of four. Shortly after dinner, we would watch TV for a bit and then off to bed for the routine to begin again. However, some of my fondest memories were the days I had doctor’s appointments. Those days were not only pleasant memories because I got to skip school for the entire day, but chiefly because I had the opportunity to go to work with my mother.

Your grandmother worked at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU), the historically black college in Tallahassee, Florida, nearly 40 miles, or roughly forty-five minutes, from our home in southwest Georgia. By the time I was six, she had already been a secretary in the Department of History, Political Science, Geography, Public Administration, and Economics for nearly fifteen years. I remember those car rides very vividly. Leaving home before the sun rose, we had to switch the radio station as we traveled closer to the Georgia/Florida border to ensure a stronger signal from the local black station.

When we arrived in Tallahassee, we came into town via the South Side–never driving past the state capital building, always passing a train depot, a National Guard post, and housing projects. These were among my earliest memories of arriving in one of the largest states in the union. Usually, when we got closer to FAMU, located on one of the highest of seven hills in the city, I could see the building that housed my mother’s office on the horizon. The lights from Bragg Memorial Stadium were also peeking atop the oak and pine trees–an arena where the world-famous Marching 100 band enchanted audiences for generations.

Driving to the campus from the southwestern end of the city was fascinating for this country boy–the way my mother’s Corolla darted through early morning rush hour traffic, into a historic black community, and literally, on the other side of an economically diverse neighborhood was the campus of Florida A&M. Decades earlier, the novelist James Baldwin described the scene of traveling the same route that my mother traveled to campus daily when he visited Tallahassee on February 1, 1960, this way:

“It is a beautiful campus, about a mile outside town, on the highest of Tallahassee’s seven hills. My driver seems very proud of the state of Florida for having brought it into being. He intends to disarm any criticism I may have by his boasts about the dairy farm, the football field, the guesthouse, the science buildings, the dormitories.”1

National Treasures

My earliest memories of this campus are overwhelming–mainly because we left a community of no more than fifty residents just an hour earlier. Now, I was on a college campus, one of the most respected HBCU campuses in the nation, with lecture halls that could comfortably seat the entire community of the Sixteens. Shortly after my mother pulled onto Orr Drive, she drew out a gate card from her purse to gain entrance into the parking lot that would give her quick access to Tucker Hall, the building that housed the College of Arts and Sciences, also named for the founder of Florida A&M, Thomas DeSalle Tucker, a true African Prince.2

HBCUs such as FAMU are not just local bastions. They are national treasures whose legacy is the production of remarkable citizens. These institutions developed leaders–religious, educational, and political, who forced America to deal with what James Baldwin referred to as “the Lie” of black inferiority and white supremacy.3

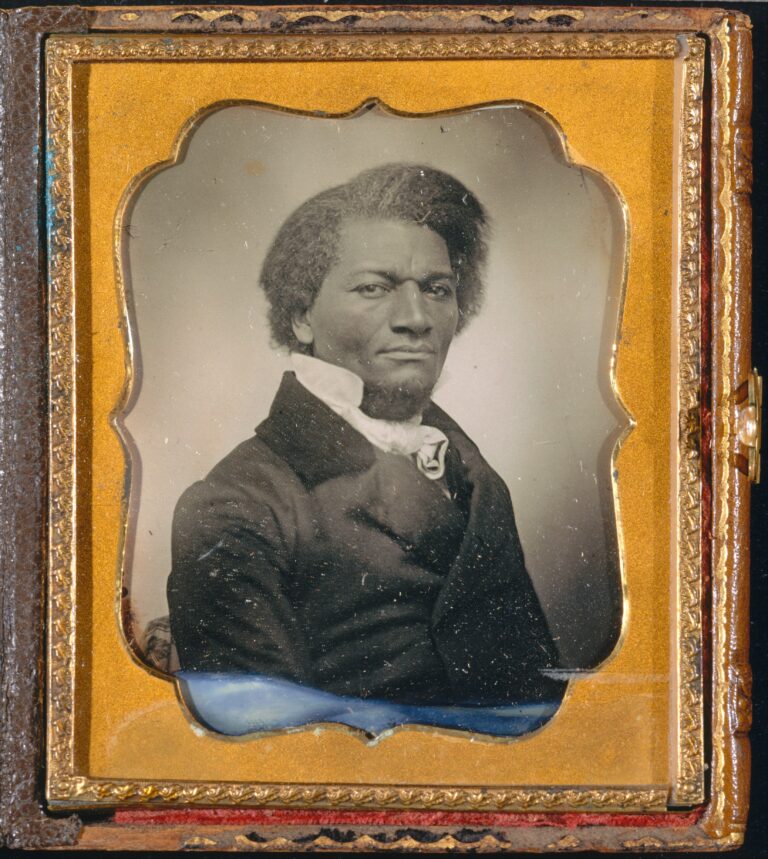

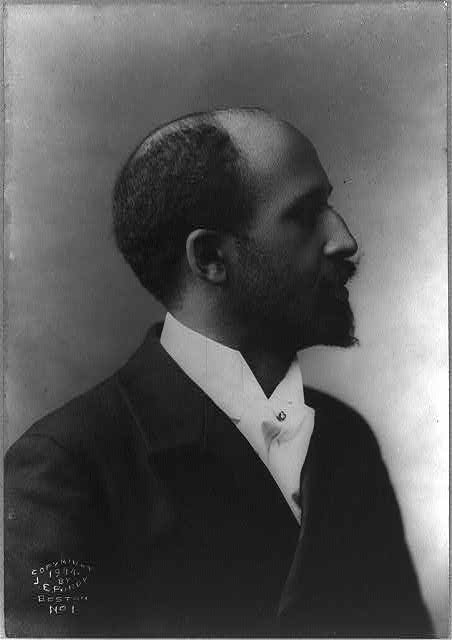

From the Fisk University alumni W.E. B. Du Bois and John Hope Franklin–scholars who informed the world of the history of Africans in America, their civilizations and their culture to the Morehouse Man, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Lincoln University’s own Thurgood Marshall–the civil rights icon who transformed the law to include black people in all aspects of the judiciary, HBCU graduates have forced America to revisit the country’s founding principles and challenged Americans to become what they claimed to be on paper. From their creation, these institutions have offered the black community access into the middle class–providing a gateway to professional careers that have elevated a segment of the black community from intergenerational poverty.4

When taking my voyages to FAMU’s campus with my mother in the early 1980s, there was a sense of purpose from the professors and a deep sense of belonging from the student body. I saw the pride and purpose firsthand, in the manner that my mother went about her job responsibilities. Never arriving late for work, your grandmother always reached campus between 7:45 and 7:50 a.m. to ensure she could have a cup of coffee before the rigors of the day began. Eva J., you wouldn’t know this, but I was terrified of elevators as a child. I would take the stairs, climbing four flights for years to avoid riding them. This phobia developed during one of my excursions to Tucker Hall with my mother. On this fateful visit, we entered the elevator on the first floor–my mother told me to press four, which would take us to the landing where her office was located. Shortly after the elevator’s doors closed, it slowly began its climb before stalling between the third and fourth floors. At first, I remember being calm because my mother was calm. In my mind, if she were cool with this, then everything would be alright. Nearly ten minutes passed, and nothing happened–it felt like we were on this elevator for years. I became frightened when my mother cried out, “We are stuck on the elevator! Press the button if anyone is out there so we can get out!” A few moments later, the elevator began slowly descending and opened on the third floor. When it opened, a well-dressed black man with an afro and full beard greeted us on the other side. My mother said, don’t get on. It’s out again. For years, when I made my visits to campus with my mother, she made me take the elevator up to the fourth floor with her. She often scolded me, “Reginald, you have to get over your fear of elevators because in your life, you will be in buildings that have more than four floors, and you won’t have an option but to take the elevator.”

Notwithstanding my grave fear of elevators, my early memories of my visits to FAMU are pleasant. My mother worked in a large office at the end of the hall–and from my assessment, she was extremely important because everyone who interacted with her referred to her as Ms. Ellis–never Erma, Erma Jean, or Jean–always Ms. Ellis. This was new to me because back home in our community, my mother was only referred to by her first or middle name. The next thing I noticed was how my mother referred to her co-workers. Sitting behind an oversized wooden desk cluttered with a telephone, Tandy typewriter, and stacks of papers, my mother would be busy answering calls, drafting correspondences for the Division Director — the man who eventually became my mentor, fraternity brother, and the individual who in many ways I modeled my career after, Dr. Larry E. Rivers. I remember asking your grandmother, “Mama, are all of the people you work with doctors?” She looked at me and laughed, responding with a grin, “They are not that kind of doctor, Reginald.”

Being relatively familiar with campus and understanding my way around, my mother would often allow me to explore–well, I should not say she permitted me to explore, as sometimes she assumed I only ventured down the hall visiting a few professors I met along the way. I found myself on the quad, watching young black college students sit on the stoop of Colman Library, engaging in post-class conversations–the more extended the talks went on, the larger the group around the diatribes morphed. Watching these young college students debate the day’s issues was riveting for a young country boy.

After walking past the library, I would wander into the Orange Room where food was served for the campus community. On any given day, you encountered students from all over the world–from the Caribbean, West Africa, Chicago, Illinois, or Miami. FAMU, like most HBCUs, was among the world’s most culturally, diasporically diverse micro-communities. In the Orange Room in the early 1980s, there was a short-order cook, a tall, dark-skinned man, who wore a university-issued white uniform with a white hat. As soon as someone walked through the doors, he greeted them with his loud, high-pitched voice–not talking to you, but to the student, faculty, or staff member placing their order. “What’s your order–hurry up; we have a long line now!” Culturally speaking, no one viewed this gentleman’s urging as rude; we all understood him and his quirks. In many ways, he was our uncle–an older cousin or brother. He wasn’t hurrying us to be meanspirited. On occasion, he was teaching the folk he didn’t know how he expected to be treated. To those he did know, however, he was simply talking trash, of which there was always a healthy dose throughout the campus, thus adding to the experience.

Eva J., there was something special about having access to FAMU at that time of my life. You are too young now to understand the significance of the giants I had the privilege of watching from a distance. Once or twice per football season, your grandmother would send me to a football game with my cousin and his dad–we would always arrive at least one hour before the fun began. Uncle BoBo was a real stickler about watching the football team stretch before the game–you understand now why I always leave home at least two hours before a home game begins.

Somebodyness

As we pulled onto campus, we would see a sea of black folk spilling out of the community surrounding FAMU, cars lined up bumper to bumper, snaking through the two-lane street headed to campus. The closer we got to the campus, the louder the music from the road, the more flavorful the smell, and the more raucous the fanbase was–it was a spectacle! Walking to the stadium was always overwhelming, seeing students interact with alumni from generations past, sharing stories with the “new school” about how they used to run the yard. Passing the tailgates and constantly running into someone we knew–being offered a quick meal, and Uncle BoBo being offered a beverage–although he didn’t drink, this sense of community was unparalleled for me at the time.

But two moments occurred during my first FAMU home game that cemented my passion for FAMU in general and HBCUs in particular. Once we made our way inside the stadium and sat in our seats, always near the 50-yard line halfway up, we could hear the rhythmic beat of drums in the distance. A few moments later, nearly two hundred fifty Florida A&M Marching 100 Band members emerged dressed in green and white uniforms and orange capes. That evening, we were playing the Golden Rams of Albany State University–their gridironers proudly representing their Blue and Gold uniforms. This game was already approaching a sellout due to the close geographic proximity of the two universities. I recall their team sprinting off the field into the Gilmore-Powell Field House for final pregame instruction. A few brief moments later, the Mighty Rattlers, wearing orange pants, a kelly green jersey with white numbers, and an orange helmet with a diamondback white rattler logo on the side of the helmet, calmly walk into the field house themselves.

By now, the band was standing at attention, half of the unit on one sideline and the other half on the other. The sun over Bragg Memorial Stadium began setting. Then the voice that became synonymous with the university, a local DJ and announcer of the Marching 100, Joe Bullard, boomed over the public address system, “Welcome Home, Rattlers!!! Your wait is over. From the highest of the seven hills in the capitol city of Florida, introducing what has become most commonly known as America’s band, the incomparably, fabulous, fantastic, number one band in America — Ladies and Gentlemen, the Florida A&M University, Marching Band — first the sound!!!”

This introduction was synced with every movement of the band. As soon as Bullard announced, “first the sound,” the band, now on the field, moments after dazzling the audience with their quick pace marching, began their pregame performance in bloc band formation. Watching over this well-trained ensemble was Dr. William Patrick Foster, adorned in a black band director’s uniform, black hat, and white gloves. What amazed me about the band and Dr. Foster was his command over this group and the respect these young student musicians had for him.

Dr. Foster would begin the pregame show on one sideline; as the band finished one selection, they rattled or marched very quickly into their subsequent formation. Meanwhile, Dr. Foster walked calmly, yet briskly from one sideline, across the field, via the fifty-yard line to the other sideline. While well over 250 band members were racing to their next spot to create their subsequent formation, their director never paused, dodged, or ducked any band member. I remarked to my cousin, “That man is about to get run over,” he responded, “That’s Dr. Foster; they know better!”

With the band in bloc formation, now facing the north endzone, Bullard asked everyone in the stadium to stand and for men to remove their hats for the playing of Lift E’vry Voice and Sing, the Negro National anthem, followed by the Star-Spangled Banner. This was the first time in my life that I heard the tune of Lift E’vry Voice and Sing. What a treat it was. Not only did the band play this so masterfully, but listening to hundreds of college students and thousands of black folk–both FAMU and Albany State fans sing this song in unison created in me a sense of pride and also a sense of shame–shame because this was an anthem that I should have known but had no prior knowledge of.

But perhaps the seminal moment of that evening that imbued a passion in the black college experience happened next. As the band created a tunnel for the football team to run through, Joe Bullard introduced someone who would become one of my many historical mentors, the university president, to provide brief greetings. Unbeknownst to me at the time, I was witnessing the creation of a new tradition- developed by a man who would become an icon. The reason that I desire to become a black college president was born that evening.

Dr. Frederick S. Humphries, comfortably wearing a kelly-green blazer with an orange shield of the university, khaki pants, and a white traveler’s shirt, took the microphone and the audience’s attention simultaneously. “Good evening, Rattlers, and welcome to our friends from Albany, Georgia.” While I don’t recall the buildup to his charge, as Dr. Humphries continued his greetings, the students began to slowly, then more enthusiastically, stump their feet. Dr. Humphries started what became known as the Rattler Charge by taking his cue like a Baptist preacher would from an encouraging deacon. Informing our guests, “We welcome our visitors from Albany, and we have a great relationship with them–but, this is Bragg Memorial Stadium, and we don’t take no crap, in Bragg Memorial Stadium. When the Dark cloud gathers on the horizon, when thunder and lightning pierce the sky, when fate is but a glint in the eyes of a fallen rattler, and hope’s a lost friend, when the sinew of the chest grows weary from the hard-charging linebacker, and the muscles in the legs grows tired from those hard-charging running back of the Rattlers, you must always remember, the Rattlers will Strike, and Strike and Strike again!!!!” As the students, alumni, and fanbase’s right hands transformed into rattler’s heads, striking and hissing with every word of their president, my love affair with HBCUs began.

There was something special about attending a black college game for this country boy, growing up in a post-segregated society that still embraced many of the trappings of the Jim Crow South. As the evening went on, I realized this campus was where I wanted to be. I felt safe here, a sense of pride and belonging–a sense of what Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. often referred to as a sense of somebodyness. I knew that when I returned home, I needed to refocus in school so that one day, I could make it back to FAMU–not as a visitor in my mother’s office or a fan attending one of the ball games, but as a student. After that point, my focus was just that: to graduate high school, go on to FAMU, and one day attend Howard University for a Ph.D. One dream came true. While my journey to the Ph.D. took me a different route, maybe you or Raila will fulfill that dream for me.

Years after my initial visits to FAMU’s campus, I read about and personally witnessed what historian Jelani M. Favors described as communitas on this campus, and how FAMU was indeed A Shelter in a Time of Storm.5

Student activism is in the very DNA of HBCUs in general and FAMU specifically. Just over twenty years prior to my initial visits to campus, student leaders at FAMU took a stance against segregation laws in the state of Florida–an activist legacy that in many ways predates the 1960s.As early as 1923, Florida A&M students protested the brutal beating of a student by a local white business owner simply because she demanded service. During the protest, however, the Interim President, William H. A. Howard was pushed by the superintendent of public instruction, J. T. Diamond to have all protesting students expelled. When Howard attempted to execute those orders, the students went on strike from classes in early October and refused to return to class until Howard was removed from office.

This standoff turned violent, however, as three of the college’s buildings were set on fire in protest against the administration’s lack of support for students’ human and civil rights during the off-campus incident. 6

That spirit continued during my freshman year in 1999. Students at FAMU protested a proposed three-tiered higher educational system in the state of Florida, which would have relegated FAMU to the third tier. Under this system, the only publicly funded HBCU in the state of Florida would have been limited to only offering undergraduate degrees.

After this proposal was announced, hundreds of FAMU students marched less than three miles to the state’s capitol and blocked traffic at the city’s major intersection for several hours. Shortly thereafter, then Governor Jeb Bush agreed to meet with student and university officials and later agreed to amend his One Florida Initiative to allow FAMU the opportunity to continue to offer graduate and professional programs.7

FAMU student activism continued well into the twenty-first century. As recently as 2020, during the nationwide Black Lives Matters protests, our students, joined by our nationally ranked football team, came out on the streets to support the movement.8

The HBCU Family

Raila, this is the spirit that you will inherit as a direct descendant of HBCU graduates. The family bond runs deep within the HBCU community. My days as a lad growing up in the country and on a black college campus were fun. Surrounded by family, I did not particularly have a care in the world. Unfortunately, this carefree life ended abruptly on the evening of July 21, 1988. Nationally, Americans will remember that Thursday evening much differently than our family will. While only eight years old, I remember July 21, 1988, very well, as it is a watershed moment in my life. Months before this hot July evening, a young North Carolina Agriculture and Technical State Institute (NC A&T) alum and civil rights activist, Reverend Jessie Jackson, Sr., barnstormed the nation, making his pitch for the presidency of the United States of America via the Democratic Party primaries. Rev. Jackson fired crowds up for his second presidential run with his campaign slogan, “If my mind can conceive it and my heart can believe it, I know I can achieve it.” During this primary season, one of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s lieutenants won 6.9 million votes, which included 11 contests, encompassing seven primaries in Alabama, the District of Columbia, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Puerto Rico, and Virginia. Reverend Jackson also won four caucuses: Delaware, Michigan, South Carolina, and Vermont.

This HBCU alum fell short of earning the nomination in the fall election of 1988, conceding to Michael Dukakis, Governor of Massachusetts in what was increasingly becoming the sprawling black metropolis of Atlanta, Georgia, and home of three renowned private HBCUs. Jackson wowed the audience with his charisma and call for party unity on Tuesday, July 19, 1988–just two nights before my life changed forever. I don’t remember much from that evening. However, I recall how proud my mother and father were to vote for Rev. Jackson during the primary and how they were even prouder knowing he would deliver a keynote address during the Democratic National Convention in our home state.

While Jackson’s appearance at the convention is fuzzy at best, I remember perfectly the evening that Governor Dukakis accepted the presidential nomination–just two days later. I can almost see that Thursday evening. I was awakened early that morning by your grandfather, John Ira Ellis, as he was preparing to leave home to head off to work. Per usual, your grandmother was already off to work, and your aunt and I were home for summer break. Like clockwork, your grandmother arrived home at 6 p.m. However, your grandfather, who would have typically come home no later than 5:30 p.m., had not returned. In the distance, I saw his green and silver Ford F-150 speed past Ellis Lane and head towards the county seat of Cairo (pronounced Karo). I assumed he was running an errand and would return home shortly after. As the hour approached 8 p.m., a severe thunderstorm rolled in, not uncommon for the dog days of summer in the deep south. Your great-grandmother, Alegria, came to our house as she was gravely afraid of bad weather. Before the storm reached its climax, your great-grandmother, grandmother, aunt, and I sat in front of our TV and watched as Dukakis accepted the nomination. Neil Diamond’s “The Best America,” Dukakis’s theme song for the ’88 campaign, is engrained in my memory — not for the jubilation expressed by the campaign, but due to the tragic news delivered shortly after that.

As the balloons and confetti began dropping from the ceiling of the Omni in Atlanta, we were forced to unplug our television due to the severe lightning and fear of our ungrounded house being struck. Sitting quietly for about an hour waiting for the storm to pass, we received a call at the door, which for this time of night, shortly after a storm passed, was extremely uncommon. My mother and I went to the back door to find Uncle Roosevelt and my cousin Pete. For whatever reason, I did not hear the words of my uncle–I just saw my mother tumble over in deep grief and my grandmother howl in the background, “My baby!!!” With all the commotion, my nerves were so unsettled that I vomited right where I stood. I had just learned that your grandfather was killed in a single-car accident while traveling back home from Cairo. He was only thirty-six years old.

One week later, my father’s funeral services were held at his home church in the Sixteens. My father’s brother, my uncle, and your great uncle, Dr. Rufus Ellis, Jr., helped to plan the arrangements. Uncle Tank, as we affectionally call him, was the first person I knew who earned a Ph.D., a proud member of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc., and an alumnus of Morris Brown College in Atlanta. Rather than choose family friends and associates to serve as pallbearers for my dad, he decided to call on his fraternity brothers. However, my father was neither a college graduate nor a member of the oldest black Greek-lettered fraternity–I was not aware that the brothers served as my father’s pallbearers until I became a fraternity member nearly twenty years later. Ironically, when my mother transitioned in 2012 after a prolonged battle with breast cancer, I was honored that her active pallbearers were my fraternity brothers and local Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. chapter members.

So many people were in attendance at my dad’s services that most of the folks had to wait outside until after the services were over to express their support for our grieving family. As the doors of the church were flung open, slowly walking behind my father’s black casket trimmed in gold, I remember being in a daze. The pallbearers carried my father to his final resting ground, roughly fifty yards from the church–every step my mother was stopped by someone wishing her well, expressing their most profound and sincerest condolences. As we arrived at the gravesite and the final rites were made, one of the first faces that emerged was a face I saw every time I went to work with my mother, Dr. Larry E. River, my mother’s boss. He came over and hugged my mother, asked if she needed anything, and promised her at that moment that he would ensure that I would be okay. Raila, you know Dr. Rivers as Daddy’s mentor and our neighbor, but he is also acutely responsible for me being the professional I am today.

So now, you keenly understand why HBCUs are vital to me and why we, as a family, are proud supporters of them. It was HBCU faculty, staff, students, administrators, and support that imbued a sense of pride, belonging, and somebodyness in me that has molded my life since before I can remember. My story is not unique, however. This story has been told repeatedly by hundreds of thousands of HBCU alums throughout the nation. This, however, is the first time I am sharing it with you. It is why I believe it is vital that you both consider an HBCU as your institution of choice.

Writing this letter has given me the opportunity to reflect on how far I have come. A kid who, for most of my life, grew up in a single-parent home, raised by an office manager in the department of history–later becoming a historian at the same HBCU where my mother worked–but also being elected to serve as a councilor of the American Historical Association and co-chair of the America250 history task force. Honestly, I would have never doubted that I would be where I am today–not because of my ability, but because of what my mentors at my HBCU saw and pulled out of me. The pride Dr. Humphries poured into his students–challenging corporate America to hire more of them and R1 institutions to admit us into their Ph.D. programs, law, and medical schools to ensure we had full access to the American Dream. Because of this training, I never felt the imposter syndrome when I entered spaces where I was one of the few people of color. Conversely, I understand that it’s my responsibility not to merely represent Reggie Ellis nor the Ellis family in these spaces–but the community at large. This is what my HBCU fostered in me throughout my life.

The Nation Owes HBCUs

Today, nearly one hundred-seventy years since the founding of the first black college and after the Sweat v. Painter and Brown v. Board of Education cases, black colleges, while only representing three percent of the total number of higher educational institutions–are still responsible for more than ten percent of the black student body population. 8

Most impressively, black colleges are where graduates earn STEM degrees: forty-six percent of black women who earned degrees in STEM disciplines studied at an HBCU. Meanwhile, black colleges are still producing black scholars and practitioners for the next generation more than any other institutions.My final reflection is where we are as a nation ahead of the 250th anniversary of America. In your lifetime, Eva and Raila, many of the rights and privileges gained before the Bicentennial in 1976 have been eradicated. As young ladies, you have fewer rights over your body than your mother and grandmothers had most of their adult lives with the abolishment of Roe V. Wade. Likewise, the concepts of diversity, equity, and inclusion in higher education via affirmative action can no longer be considered in college admissions–which has already impacted the number of black folks admitted into “prestigious” institutions of higher learning in California and elsewhere. Lastly, white supremacy and hate crimes targeting black folk have exploded since 2016, to the point that even President Joseph Biden was forced to acknowledge in 2023 that white supremacy was a national threat.

Since 1837, at what is now Cheney State University, black college campuses have provided a safe space for young black folk to grow into the holistic people they would eventually become—not unbothered by, but mostly sheltered from the tentacles of white supremacy, if only for a few years. That small window provides time for these young learners the opportunity to grow and develop as analytical thinkers, build networks, and cultivate skills to help push America to become a perfect union. This is why, Eva and Raila, HBCUs will be more important in the twenty-first century than they were in the twentieth century–if we are to help, to borrow a phrase from Langston Hughes, “America be America again.”

Reginald K. Ellis, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of History and African American Studies at Florida A&M University.

footnotes

- 1 James Baldwin, “History is a Weapon: They Can’t Turn Back,” Mademoiselle (February 1, 1960).

- 2 Reginald K. Ellis, “Florida State Normal and Industrial School for Coloreds: Thomas DeSalle Tucker and His Radical Approach to Black Higher Education,” in Repression, Reform, and Revolution: New Studies on the Long Civil Rights Movement (Gainesville: The University Press of Florida, 2018), pp. 10-27. Tucker’s mother was the hereditary princess of Sherbro, Sierra Leon.

- 3 Eddie Glaude, Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and its Urgent Lessons for our Own (New York: Crown, 2020).

- 4 https://uncf.org/wp-content/uploads/Social-Mobility-Report-FINAL.pdf

- 5 Jelani M. Favors, Shelter in a Time of Storm: How Black Colleges Fostered Generations of of Leadership and Activism (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

- 6 https://www.thefamuanonline.com/2012/10/03/the-fires-of-famc/.

- 7 https://www.sun-sentinel.com/2000/02/09/governor-agrees-to-amend-his-one-florida-initiative/.

- 8 On Sweat v. Painter, see https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/339/629/. On Board of Education, see https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/brown-v-board-of-education. Recent data on HBCUs can be found here: https://uncf.org/the-latest/the-numbers-dont-lie-hbcus-are-changing-the-college-landscape.