After the Core

Is the liberal commitment to a core citizenship requirement in higher education the solution to our civic deficit - or the problem?

THIS ESSAY IS PART OF THE SPECIAL ISSUE “AFTER LIFE: IDENTITY AND INDIFFERENCE IN THE TIME OF PLANETARY PERIL.” IT FEATURES PAPERS PRESENTED AT THE INAUGURAL SYMPOSIUM OF THE DEMOCRACY INSTITUTE AT THE AHIMSA CENTER AT CAL POLY POMONA, WHICH WAS CO-SPONSORED BY THE INSTITUTE FOR NEW GLOBAL POLITICS, IN MARCH 2023.

We find ourselves in a moment when debates about the content of, and the context for, a mandatory “core curriculum” is back in the news–in part because of the political rhetoric and legislative efforts of Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. DeSantis’s legislation is meant to “ensure Florida’s public universities and colleges are grounded in the history and philosophy of Western Civilization; prohibit DEI, CRT and other discriminatory programs and barriers to learning; and course correct universities’ missions to align education for citizenship of the constitutional republic and Florida’s existing and emerging workforce needs.”

DeSantis reminds us that discussions of curriculum are not merely “metaphors” for questions of democracy or identity but are constitutive of them. While there has been greater focus on what DeSantis feels must not be taught (critical race theory, DEI), I want to look at the degree to which what he insists must be taught–namely, a core curriculum based on ideas of Western civilization and citizenship–reflects the norm of what has historically constituted the Core. That is to say, I start with Ron DeSantis not because his position represents the extreme (which it does in certain respects) but because his push for Universities taking greater responsibility for their civic duty to the nation and democracy parallels what many University Presidents, faculty administrators, and (increasingly) legislatures are also demanding.

While few Universities are touting the need for a Western Civilization requirement (at least for now), many are recommitting to the need to institute a citizenship or civics core requirement. Taking up the mantle of responsible citizenship helps Universities justify their purpose to increasingly hostile legislatures aghast at the steep price of a four year University education (even as it is the large-scale legislative defunding of education that is largely responsible for this). And yet this call for “civic” or “citizenship” education, steeped in the language of academic freedom and civil discourse, runs the risk of keeping at bay some of the genuinely democratic impulses in the University–the majority of which come neither from faculty nor University bureaucrats but from students themselves.

Because debates over a prescribed curriculum are too important to leave to politicians like DeSantis, it is critical for students and others to remain actively engaged with these questions. Firstly, it allows one of the few opportunities that students have to question what constitutes University-level knowledge and learning. Secondly, and this is something I have heard from students in many different venues, core courses that are organized around not just certain books but questions about citizenship (for instance), require that all students discuss, learn, and engage with these ideas. FLI students and students of color often feel that majority students, within an elective system, navigate their own education in such a way that they do not have to engage with such issues or questions. One student noted that even though she was insulted at the ways some of her classmates discussed questions of social class and education in a frosh core course, she felt it was important that such a conversation was happening in an academic space and that she, as someone who identified as low-income, could be a part of it.

A very promising example of such student-organized dissent is happening at the very institution in which we convened, Cal Poly Pomona. In the “Student Initiative for Justice,” part of the Ahimsa Center, we find a teach-in organized around the crucial question of “Who’s Teaching Us?”

The teach-in was an effort to bring together students and other concerned campus stakeholders to reconsider the California state version of a “core”—the American Ideals and Institutions requirement, which all students enrolled in higher education in California are expected to take. The students’ teach-in asked their peers, and the faculty, to look critically at what has come to constitute the “ideals and institutions” in the syllabi and also who teaches this requirement.

Students holding their institutions accountable for these core requirements is crucial to how we understand what Universities owe to democracy.

The Paradoxes of the “Core” Curriculum

The “core” refers to a prescribed curriculum–sometimes one class, sometimes a series of classes taken during the first or first two years of an undergraduate degree. They are not classes in skills as such (like required writing courses), but emphasize content that is either wholly shared or carefully delimited. Debates over a curricular core are a distinctly American concern since it is American (and American-styled) higher educational institutions that are based on a liberal education model–that is, an equal emphasis on breadth of subject exploration as much as depth in a chosen major. American students (for the most part) do not have to choose a specialization before they begin University or College.

There is a paradoxical relationship between a required core curriculum and ideas of American democracy rooted in the free market. This was pointed out early on by Charles Eliot, the late 19th-century President of Harvard, who saw the highly prescribed curriculum of most American Universities as antithetical to the American nation or the very idea of freedom. The prescribed curriculum itself was the result of the roots of American higher education as a means to train young, white men for the clergy. But alongside the expansion of educational institutions was a similar expansion of those interested in pursuing higher education, and the notion of a set of texts connected to training for the Church gave way to a much broader set of principles.

In light of this, Eliot argued for education defined, not through a single Core curriculum, but through what was called the free elective system. Unlike their European counterparts, American students were far less encumbered by (European/Western) history and culture: “He is absolutely free to choose a way of life for himself and his children; no government leading-strings or social prescriptions guide or limit him in his choice. But freedom is responsibility (Charles Eliot, 1869).” American students could be taught the value of freedom of choice and competition (with one another but also between courses, disciplines, and institutions) that marks the free market.

Those who argued against Eliot for a more prescribed curriculum for students also employed the language of freedom and democracy. Rather than the freedom of the market, they evoked the freedom of the citizen. An education rooted in the Classics, the basis for one kind of “liberal education,” was what was required for the free citizens of Athens and should therefore also be used for the free citizens of the United States. But in the late 19th century, such a Classical curriculum (centered on the study of Greek and Latin) was already being eclipsed (in Britain as much as the United States) by a more Victorian emphasis on knowledge of English-language classics: Shakespeare or Milton.

It is this peculiar amalgam of Classical and English-language “great books” that came to constitute what DeSantis (and others) refer to as the “Western tradition.” In fact, by the later 20th century, there emerged a whole publishing industry around producing “great books” for higher educational institutions offering Western civilization core courses.

Another paradox in the development of core classes is the peculiar relationship between two of the major types of core classes. While courses based on Western civilization foreground a “shared” culture (defined through a set of aesthetic literary choices of various European texts), classes on citizenship usually emphasize US history and the histories of particular civic institutions or texts (the Congress or the Constitution).

The Western tradition curriculum, on the surface, aspires to a certain disinterest in contrast to the more didactic (and usually more openly ideological) curriculum of citizenship courses. Yet defenders of liberal education insist that the various aesthetic (literary) choices are meant to impart a certain set of “liberal” values and create a shared history and culture. By the twentieth century, such (western) civilization courses were seen as surrogates for citizenship courses—“civilization” seemingly used interchangeably with a concept of “citizenship.

But this sleight of hand–civilization and citizenship–was not so easily resolvable and remained a site of tension in the history of the core. Not only were the majority of the “great works” that constitute the western tradition not American, but the very idea of a “great tradition” sat uneasily with the American sentiment against anything that smacks of snobbishness. Any curriculum based in the (European) tradition ran the risk of appearing as a part of the very aristocratic culture against which the American republic defined itself. Judith Shklar draws our attention to this peculiarity of American education, whose roots she notes lay in schooling for citizenship rather than charity schools, but whose curriculum was foundationally beholden to Europe. “Schooling is not unambiguously democratic. History and literature reflect a class-ridden past, wholly unsuitable for the minds of young republicans. That was one of the reasons why “the literary, erudite, intellectual and scientific class” was given to snobbish airs (Shklar, 1984, 112).”

This seeming contradiction was pointed out in one of the most important 20th-century reports on American education called the Higher Education for American Democracy Report (1947) or the Truman Commission Report. It was the first time a President had called for a national report on colleges and Universities. In terms of arguments for (or against) a Core curriculum, the Commission intentionally shifted away from the language of “liberal education” to the language of general education–the term that is used most widely in higher education currently.

The Commission felt that even within the larger framework of an elective system and increasing specialization (especially a post-war shift towards science and technology), Universities were still responsible for teaching students their “common cultural heritage toward a common citizenship,” (again the somewhat awkward integration of culture and politics) and that this should be done through general education–which was not meant to be substantively different than the liberal education based in great books–but which should not appear to be “snobbish” (in Shklar’s language): “General education undertakes to redefine liberal education in terms of life’s problems as men face them . . . General education is liberal education with its matter and method shifted from its original aristocratic intent to the service of democracy (Higher Education for American Democracy, 1947).”

Yet it is not obvious how a general or liberal education can be made to serve the interests of democracy. How or why does reading Aristotle or Shakespeare lead to either an understanding of democracy or, more importantly, the values of republican citizenship? Martha Nussbaum, reflecting a broadly held liberal consensus, suggests one way: “Literature makes many contributions to human life. But the great contribution literature has to make to the life of the citizen is its ability to wrest from our frequently obtuse and blunted imaginations an acknowledgment of those who are other than ourselves, both in concrete circumstances and even in thought and emotion (Nussbaum, 2008, 143).”

Nussbaum shifts the emphasis from arguing for the inherent superiority of Greek and Latin texts to what the study of literature does–not merely teaching us our shared culture but developing in us the ability to empathize. Empathy then becomes the basis of genuine “democratic citizenship.” While “liberal education” is no longer connected to producing clergy, its origins reveal themselves in the almost religious belief in the inherent power of great books to transform the self.

In this case, the power to instill the value (and aptitude) for genuine empathy which will allow us to be better citizens, much as genuine faith would make us better clergy. We might read Nussbaum’s emphasis on empathy as echoing one of the foundational thinkers of education in the context of democracy, John Dewey, for whom democracy “is more than a form of government; it is primarily a mode of associated living, of conjoint communicated experience.” (John Dewey, 1916, 101)

Education for Citizenship

In spite of various efforts to conjoin the efforts of the great books/ liberal education tradition with an education for citizenship, they remained (and remain) quite distinct. In fact, soon after the first World War and parallel to the development of the Western culture or Western civilization requirement, there emerged arguments (and curricula) aimed at shared courses that put (American) civics and citizenship at their center. The goal was expressed in more explicitly political terms: the need (on the one hand) to remind Americans of their shared history of democracy with Europe (and thus justify the need to militarily defend Europe should the need arise) and to educate and integrate immigrants (and their children) into a shared sense of American culture and citizenship.

One example of this was the curricular effort in 1920 by Stanford historian Edgar Robinson to launch a course on the “Problems of Citizenship.” Robinson was explicit about what he saw as the purposes of a course on citizenship: “The purpose of this general course is one of service to the state. In the modern day it is essential that the disciplined and cultured college graduate have a conception of the state, and of his relation to it, not only for his own sake, but also for the sake of the mass of the people. Here at the outset of his opportunity to better prepare himself for life, the emphasis should be upon public, not private, objectives (Robinson, 1920).”

In the current moment, many have taken up Robinson’s call for the University, through its curriculum, to “better prepare” the student for their public (civic) life. For instance, in a recent book, What Universities Owe Democracy, Ron Daniels (the President of Johns Hopkins) insists that higher education must recommit to requiring that its students be provided with an education for citizenship. Daniels and his co-authors feel that with greater knowledge students would learn what defines a liberal democracy and how best to support it. “Our colleges and universities–once the exclusive province of white men from a narrow geographic region–are today among the most diverse institutions in our society. They ought to be on the vanguard of this grand, historic project, modeling what productive citizenship looks like in a world of difference, and yet they have lapsed in this responsibility (Daniels, 2022, 197).”

I see the renewed emphasis on the need for a common “core” and courses on citizenship at this moment as a response to two recent events: the protests after the killing of George Floyd and the January 6th attacks on the US capitol. Students have pushed Universities to consider their role in the larger questions of inequality, justice, and democracy–that is, to be more “active.” The problem for Daniels, is that while there are many individual courses in history or political science or government or the Constitution, these are all elective. Instead, says Daniels, what is needed is to institute “a Democracy Requirement,” into all University curricula.

Among the “alarming trends” that Daniels sees as a threat to democracy (glossed here as productive citizenship in a world of difference) on campuses is “the hyperpolarization and self-segregation that have undercut our ability as educational institutions devoted to expressive freedom to speak to one another in a way that promotes compromise and mutual understanding (Daniels, 2021, 21).” This is echoed again when he discusses the need for curricular citizenship requirements at the University, where (even as he notes that these types of controversies are few and far between) Daniels discusses the efforts of students at Johns Hopkins to “cancel” a talk being given by Tucker Max (a writer of a genre called “fratire”). Although it may initially appear that the purpose of creating a “democracy requirements” is to remind students of the values of liberal democracy and alert them to the threat of authoritarianism (from thwarted coups or efforts to steal elections, for instance), there appears to be another threat that University Presidents fear: the authoritarian tendency of College students themselves.

Sigal Ben-Porath’s book, Cancel Wars, names the threat explicitly–the “cancel culture” of students stands in the way of the University’s civic role in a liberal democracy–namely to educate students in democratic citizenship. Ben-Porath carefully navigates the responsibility of institutions to promote inclusion while also maintaining a commitment to academic freedom. But the title of her book and some of her examples also feeds into a narrative by the right that the “problem” of democracy on campuses are students themselves, particularly (left) activists. While it is often (right) activists on campus (and elsewhere) who invite such intentionally provocative speakers, the campus arguments about “cancel culture” see conservative students as those that need protection since they feel they have to self-censor for fear of being “canceled.” I am unconvinced that the decision of some students to rethink or reconsider what they might say aloud represents the real crisis of democratic norms. Yet, this sentiment is not only repeatedly expressed but linked to partisanship, the decline of civility, and a more general drop in “democratic thinking.”

More troubling is that the fear of individuals that they will be “canceled” because they hold particular political views sets up an equivalence with another dynamic that is widely reported (and documented)–-the multiple ways that first-gen students, students of color, LGBTQ+ students, etc., are excluded through (micro)aggressions and sometimes overt aggression from full participation on campus by faculty, administrators, and their peers. We would never describe such communities as being “canceled” by white supremacy. Instead the “cancel war” is evoked when students dissent, when they refuse to be spoken to in a certain way, or they resist the use of casually racist language in the name of freedom of speech. They are being “uncivil,” not behaving with the kind of decorum expected for a civically virtuous citizen (or nation).

There is another reason that Universities, as much as they would like to claim that theirs is the work of democratic education and engagement, are often stymied in that effort. I do not feel it is because of their need to uphold academic freedom but because of the very undemocratic way in which that academic freedom is imagined. This is explicitly articulated in one of the most important “cancel culture” books of the 20th century, Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind. Saul Bellow, in the introduction, sums up the argument in this manner: “The heart of Professor Bloom’s argument is that the university, in a society ruled by public opinion, was to have been an island of intellectual freedom where all views were investigated without restriction. Liberal democracy in its generosity made this possible, but by consenting to play an active or ‘positive,’ a participatory role in society, the university has become inundated and saturated with the backflow of society’s ‘problems’ (Saul Bellow, 1987, 19).”

For Bloom and Bellow, the utopian possibilities of the University lay in its standing apart from the rest of society, but once the University allowed itself to participate in the very liberal democracy that made it possible, it opened itself to contamination from society’s “problems.” It is worth noting that what is described as “an island of intellectual freedom” has been historically committed to the very undemocratic practice of keeping the vast majority of people out of its hallowed halls–women, the working class students, and ethnic and racial minority students. There is an implication that the absence of such students and their demands that Universities be a part (and not be apart) from society threatens any rigorous intellectual exchange of ideas.

We can see DeSantis’ legislation as beholden to Bloom’s book, which still represents the clearest articulation of a conservative perspective on Universities and intellectual freedom. In contrast, most recent books take great pains to celebrate and insist upon diversity and inclusion as part of the University’s mission, and yet I am concerned that the renewed emphasis on the need to protect academic freedom allows some to imagine (re)creating the kind of University championed by Bloom.

One might see the recent Supreme Court ruling against affirmative action as a part of such a project. Among other things, the judgment sets the stage for Universities, particularly elite institutions, to once again become “islands” of academic freedom with fewer African American or Latine students on campus to dissent or demand that Universities actively participate in democracy. This threat is emphasized in Justice Sotomayor’s dissent in the Students for Fair Admission vs. Harvard University case: “The Court subverts the constitutional guarantee of equal protection by further entrenching racial inequality in education, the very foundation of our democratic government and pluralistic society (Sotomayor, Dissenting opinion, 2).”

Arguments about the Core and the case for affirmative action intersect. The conditions that allow for greater racial equality (and pluralism) also allow for greater epistemological challenges. Both lie at the core of democracy.

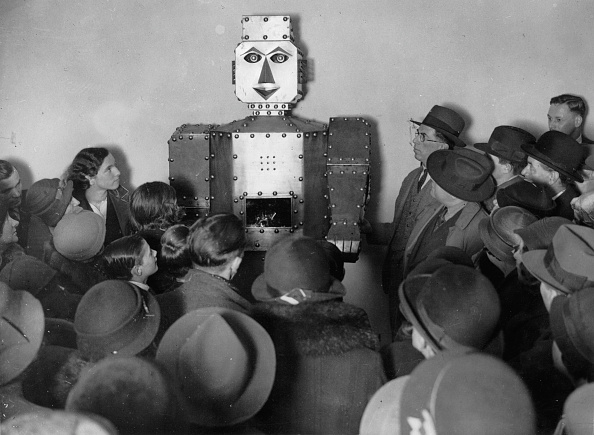

We see this exemplified in the photograph at the top of this essay, an indelible image of Jesse Jackson’s visit to Stanford in 1987 (soon after his Presidential bid), in which he and a “rainbow coalition” of Stanford students protested Stanford’s “Western civilization” core requirement. The banner being held up reads “Marcus Garvey, Kwame Nkrumah, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Samora Machal: A legacy of progressive leadership ignored by Western culture.”

The Western culture is a reference to the core frosh requirement. Jackson is surrounded by a diverse group of students who were invested and committed enough in their own learning that they were willing to protest, not the end of the Core, but its transformation into something that spoke to them. The listing of Black political leaders and thinkers suggest the critical democratic importance of including diverse intellectual and epistemological traditions in anything that is required of all students. In making this demand, the students use the word “legacy.”

The students (and Jackson) are calling out the ways the Western civilization writes out the intellectual legacies which also constitute it–the critically important intellectual traditions of Black dissent against slavery and colonialism. And the presence of these students also challenges another legacy–what is called “legacy admissions” which give (disproportionately) wealthy, white students whose parents were alumni a disproportionately greater chance at admissions. We seem further and further away from the idealistic and democratic promise of the Truman Commission and its efforts to create general education.

Dr. Parna Sengupta is Associate Vice Provost and Senior Director of Stanford Introductory Studies at Stanford University.

Bibliography

Ben-Porath, Sigal. (2023). Cancel Wars: How Universities Can Foster Free Speech, Promote Inclusion, and Renew Democracy. University of Chicago Press.

Bloom, Allan. (1988). Closing of the American Mind. Simon and Schuster.

Daniels, Ronald. (2021). What Universities Owe Democracy. Johns Hopkins Press.

Dewey, John.(1916). Democracy and Education. MacMillan and Company. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/852/852-h/852-h.htm

Eliot, Charles. (February, 1869). “The New Education,” The Atlantic.

Nussbaum, Martha. (April 2008). “Democratic Citizenship and the Narrative Imagination.” Yearbook of the National. 107 (issue 1), 143-157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7984.2008.00138.x

President’s Commission on Higher Education. (1947). Higher Education For American Democracy: A Report of the President’s Commission on Higher Education. https://ia801506.us.archive.org/25/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.89917/2015.89917.Higher-Education-For-American-Democracy-A-Report-Of-The-Presidents-Commission-On-Higher-Education-Vol-I—Vi_text.pdf

Shklar, Judith. (1985). Ordinary Vices. Belknap Press.

Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, 600 U.S., No. 20–1199. (2023) (Sotoymayor, Dissenting opinion). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/20-1199_hgdj.pdf