Redesigning Cities for a World Beyond Cars

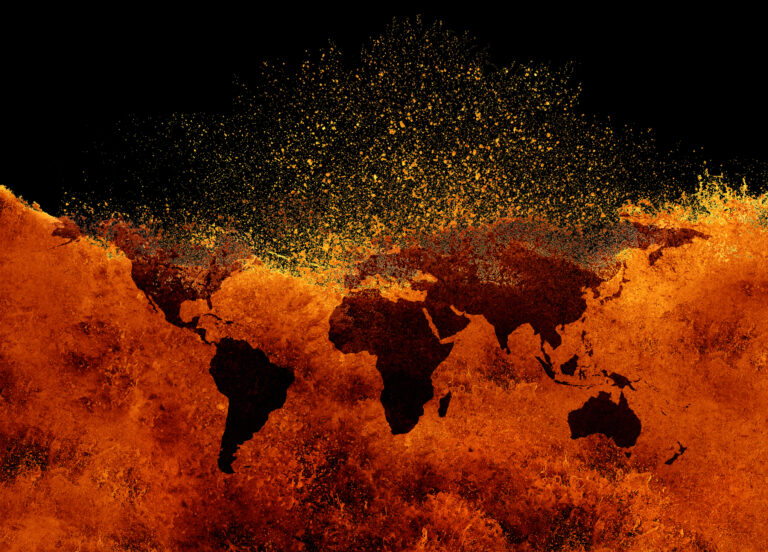

The world is burning. 2023, like most years in the last decade, broke records for heat and extreme weather. We are starting to see those extreme weather events significantly affect crop yields, and those events are increasing in intensity and frequency. The world’s scientists are warning humanity that the window for effective climate action that would forestall a more severe catastrophe is rapidly closing. In short, we don’t have time to waste. How can one read this and not act with all deliberate speed and effort?

In North America and in California, where I live, transportation comprises the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, outstripping agriculture, power generation, and industry. Climate change is a major reason to take transportation issues seriously, both as a problem and a solution. We must think about these issues systemically instead of as a simple matter of switching consumer choice about cars, an approach Paris Marx has thoughtfully critiqued:

Instead of seeing EVs as one piece of a plan for more sustainable transportation, America has focused on using EVs as a one-to-one replacement for gas guzzlers. But this one-size-fits-all solution fails to address our broader transportation problems, meaning emissions targets are likely to be missed and other transportation problems will continue to go unaddressed.

This much is clear: switching to electric cars (especially the behemoths being marketed to consumers in North America), though necessary, is not sufficient to meet carbon reduction targets set by the Paris Climate Accords.

Car Harms

More importantly, electric cars do not address any of the myriad other negative externalities of car dependency. They may even make some worse, by producing more fine particulate pollution, more road deaths, and greater transportation inequity. According to a recent study that surveys the history of the automobile, cars and the systems that have made them so central to modern life—what scholars call “automobility”—may have resulted in the deaths of some 60-80 million people and the serious injury of another 2 billion across the globe.

Inflicting an annual average global death toll of over 1.6 million, cars are one of the deadliest products unleashed on humanity. Yet in the U.S. and many other countries, government policy virtually requires car ownership to access basic needs. Urban land use designed around the automobile reduces the utility and convenience of more sustainable, affordable, equitable, and efficient modes of transportation such as transit, walking and biking.

The primary beneficiaries of these policies have been, of course, the auto, oil, and related industries. What is less obvious is the degradation of public space. We must note too the essential social disfranchisement of those who cannot drive because of age, poverty, or disability, as well as those who choose not to, for ethical or other reasons. The hegemony of the automobile diminishes our social and democratic capacity in innumerable ways. Switching to electric cars won’t change this.

To put it bluntly, we must imagine a future beyond the auto industry’s vision of what our cities should look like. We must create more equitable, affordable, and truly sustainable transportation systems that center people of all ages and abilities in their design. At a moment of climate crisis, it is all the more imperative that access for people walking and those in mobility chairs become the basic unit of transportation design in our cities.

Toward Egalitarian Mobility

Walking is the essence of democratic mobility. The democratic, egalitarian city is one that is designed around people walking or in mobility chairs. Its design must move beyond the prevailing American vision of cities promoted by General Motors in its “Futurama” exhibit at the 1939 World’s Fair: a fantasy of private enjoyment as one moves through public space. A car-first city prioritizes what historian Peter Norton calls “transportation consumerism” over “transportation sufficiency.” It is this paradigm in which the electric car serves as the “sustainable” consumer choice.

A city designed around the private ownership of automobiles is inherently hierarchical, and a city that prioritizes the private automobile is one that prioritizes access according to wealth and power. Andre Gorz, in his classic 1973 essay, noted that private automobility creates a social ideology of individualized, consumerized private mobility that pits each against all, and only worsens as it proliferates. And proliferate it must if the industry that produces it is to be served.

A new vision of urban mobility must not only address transportation emissions, but a whole range of other social issues from housing affordability to equitable access to the life of society. The barriers to reimagine our cities beyond the private automobile are not immutable or merely technological, they are political. Those political barriers are rooted in a 100-year campaign by the auto industry to reshape our built environment and, more importantly, profoundly shape our imaginations about what cities and mobility are supposed to look like.

Breaking Up with Cars

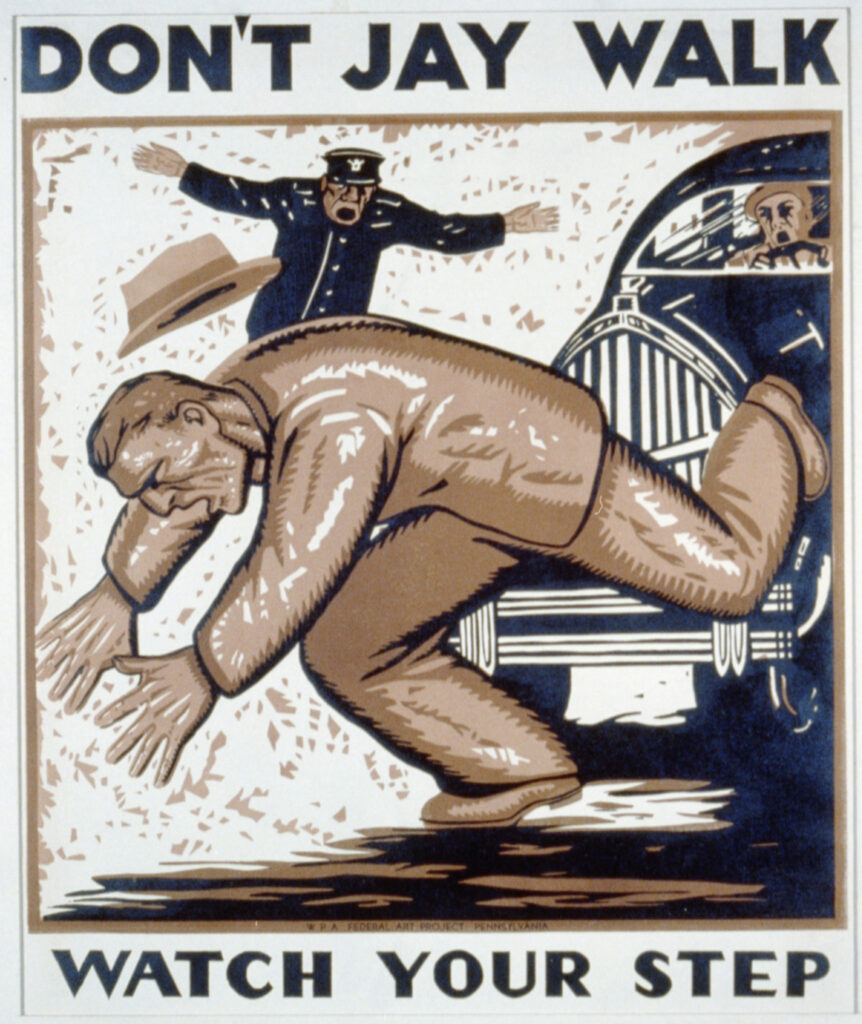

Thanks to the work of Peter Norton and others, we now know that there has always been an underreported resistance to the redesign of cities around the car. The industry used its influence to shape government policy, laws, and cultural norms around the radical reconfiguration of public space and urban geography. In the 1920s, as automobile ownership began to spread in the U.S., city leaders were confronted with a backlash against the rising death toll on city streets, as angry citizens sought to limit the incursion of cars onto streets that had previously been sites of human activity, including play space for children.

Calls to ban cars from certain areas of the city or limit the speed of cars on city streets to 5 or 10 mph alarmed automotive interests, who referred to themselves as “Motordom,” and led to an industry-backed campaign that sought instead to radically restrict the historic right of pedestrians to cross the street. They coined the term “jaywalking” as a pejorative, a “jay,” being a slang term for a rube, a bumkin, an uncouth person, and sought the help of civic groups to shame those who did not defer to the use of the public roadway by machines. Progressive Era engineers sought to bring “order” to the “chaos” of the streets and demarcated “crosswalks” where pedestrians were allowed to cross while the rest of the roadway was to be reserved for the machines and their owners, who were increasingly seen as the avatars of mechanical and industrial progress. Roads and cities weren’t “made for cars,” they were re-made around a vision literally sold by the auto and oil industries.

Understanding the origin of car dependency and what psychologist Ian Walker calls “motonormativity” is critical if we are to change it.

Historians have recently begun to challenge the “love affair” thesis that dominated early histories of the automobile, a thesis that was itself promoted by the auto industry in the early years and too often uncritically accepted by mid-20th century automotive historians.1

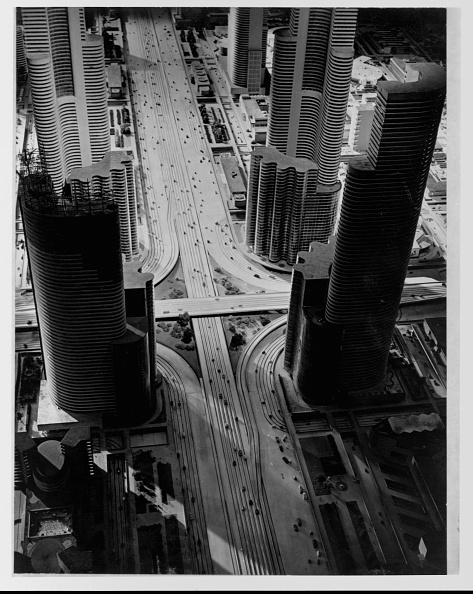

Having established primacy on the public streets by the mid-1930s, American cities were confronted with another side effect of mass automobility: traffic congestion. The problem, a geometric one related to the fact that if each individual needs approximately 200 square feet of road space in which to move through public space, that space will quickly fill up and obstruct the movement of people. A related problem was that people using more spatially efficient modes of transport, such as streetcars or buses, were also caught in the congestion created by car owners. Moreover, where to put all of the cars, which sit empty most of the time when not in use? As new car sales slowed during the Depression years of the 1930s, Shell Oil and General Motors developed an elaborate vision of the “City of Tomorrow,” which was radically redesigned to facilitate the mass ownership of automobiles. This effort began in the mid-1930s, but reached a wide audience at GM’s “Futurama” exhibit.

Implementing the auto industry’s vision of the “City of Tomorrow” involved a complex set of changes to land use and transportation, much of which was shaped by the structural racism embedded in American society in the mid-20th century. Sprawling suburban development designed to accommodate mass automobility exacerbated and reinforced residential segregation. Single family detached housing was often intended to exclude nonwhites, and the federal highway program was part of a broader “urban renewal” agenda that decimated urban communities of color and led to mass displacement. The highways themselves were designed to enable suburban commuters to reach jobs in the city while taking a large portion of the tax base out of the city and leaving “inner city” governments with a shrinking tax base and growing social needs.

Those highways continue to divide communities and leave a legacy of environmental racism with higher levels of pollution, noise, and traffic danger to this day.2

Systems of power are tangled and ubiquitous. In order to understand the magnitude of car dependency, we need to understand the ways in which public policy has virtually mandated car use and punishes those who don’t drive. The auto industry has effectively reshaped society around what one scholar calls “automobile supremacy,” through mundane policies such as zoning, parking mandates, insurance, tax law, traffic regulation, and the massive public subsidy for highways. We often hear the refrain that these policy choices are merely a reflection of market preferences, but the policies have made one choice the only one most people can reasonably make. State-mandated free parking alone provides a massive subsidy to drivers, distorting market choices and tilting the playing field heavily toward driving.

Moreover, there are opportunity costs most drivers do not see. Curb space on many streets, used almost exclusively for parking, could be used instead for transit priority lanes or protected bike lanes that would incentivize those choices. Instead, public policy prioritizes the storage of private property in the public right-of-way, degrading the alternative choices. The inherent efficiency of the bus is undercut by the inefficiency of roads clogged with private automobiles; and people on bicycles are forced to “share the road” with dangerous cars. Given these hidden and overt subsidies for driving, how much of a “choice” is it?

Community over Cars

Our sense of community is also profoundly affected by our transportation choices. Researchers have noted that people who walk, bike, and take public transportation are more connected to their physical and social surroundings by virtue of the variety of sensory experiences, shared space, and diverse social interactions we experience in public space. Rather than an “individualistic and disconnected” experience, mobility is inherently social. When the vast majority of people choose to move through public space in a locked, climate-controlled, soundproofed enclosure, the social disconnection is amplified. Drivers navigate public space in an enclosed private space, isolated from others and in competition with one another for ownership of public street space and car storage space.

When the need to accommodate the mass ownership of private automobiles requires spatial and geographic decentralization, it further diminishes the human connections necessary for a healthy public realm resulting from spatial and geographic dispersion. The solipsism of driving alone is one of its appeals, but when that becomes our primary mode of public interaction it diminishes a sense of shared community and becomes easier to segregate ourselves from diverse social interactions.

Hannah Arendt argues in The Origins of Totalitarianism that the point of totalitarian systems is to make the individual powerless, to render them/her/him moot in the face of the overwhelming nature of the system. We catalogue the death toll, but we are made to feel powerless to change it. Worse, in the U.S., our “traffic safety” messaging puts the onus on the individual, relying on humans in all their messiness, to consistently operate 2-ton, 500-HP machines responsibly at all times and for everyone else—even children–to maintain perfect behavior at all times around them. What could possibly go wrong? When this inevitably fails and “accidents” happen, our media and legal system look to place blame, either on victim or perpetrator, but rarely look at the engineered systems in which these repeated “accidents” take place.

Growing up in suburban Southern California, I took the built environment for granted, yet my experience walking, bicycling, and taking transit forced me to confront the profound way that the design of our urban geography shapes our mobility choices. As a driver, these design policies were largely invisible to me, but on a bicycle or on foot I became conscious of the fact that these spaces were often hostile to my presence, profoundly uncomfortable and at times life-threatening. This led me on the historian’s quest to figure out how it got this way and the activist’s quest to figure out how it could be changed.

The hopeful news is that these systems can be changed with activism, organization, and effort, and change begins at the local level, creating neighborhoods that are walkable, bikeable, and with sufficient housing density to support public transportation. As more people use these modes, it builds a constituency to shift funding from highway expansion to transit expansion and creates a cultural shift that becomes an example for others. Eventually, taking back our public space from private automobiles percolates up to national and international policy levels. Doing so begins to draw down one of the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions that threaten human life itself.

In the mid-20th century, North American cities were redesigned at great expense around the private automobile. We must redesign them again around people. Whether it is supporting open streets, low traffic networks, reduced car parking, reallocation of street space for wider sidewalks, traffic calming, streetcars, bus rapid transit, protected lanes for bikes and other micromobility, compact mixed use urban design, or the like, there are powerful tools at our disposal to remake our urban fabric around people, not cars.

Redesigning cities for people will not be easy, but it can be done. Indeed, it is being done in cities around the world, as communities discover new uses for the massive amount of space consumed by cars. This rethinking of motonormativity in itself won’t solve every social and environmental problem we face, but without a vision beyond the car, we cannot solve these problems. There is much work to be done, but there’s one essential fact I’ve learned: we won’t accomplish this from behind the wheel.

John P. Lloyd is Professor of History and Co-Chair of the Alternative Transportation Committee at Cal Poly Pomona. He also serves on the Executive Board of Foothill Transit.

footnotes

- 1 An early version of the “love affair” thesis was promoted by Charles Kettering, head of research at GM, in the early 1930s. See, Kettering and Allen Orth, The New Necessity: The Culmination of a Century of Progress in Transportation (Baltimore, 1932). For a challenge to the “love affair” thesis, see Christopher Wells, Car Country: An Environmental History (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014). I use the term auto industry here to describe the constellation of industries that have a direct interest in promoting private automobile usage, from the automakers and oil industry (themselves some of the largest and most influential corporations in existence) to auto parts manufacturers, new and used auto dealerships, auto parts and services retailers, auto insurance and finance, automotive marketing, asphalt manufacturers and road building, to name just a few. There are many other industries with an indirect interest in promoting automobility, such as real estate and media and professional sports, who derive much of their revenue streams from the auto industry, but for the purposes of this essay, we shall distinguish between direct and indirect interests. Suffice it to say the social and cultural influence of the industry should not be underestimated.

- 2 See, for example, Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: W.W. Norton, 2017); Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014); Eric Avila, Folklore of the Freeway: Race and Revolt in the Modernist City (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2014); Angie Schmitt, Right of Way: Race, Class, and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America (New York: Island Press, 2020); David Reichmuth, “Inequitable Exposure to Air Pollution from Vehicles in California,” Union of Concerned Scientists Fact Sheet (Feb 2019).