Eight Lessons from the 9/11 Wars

Lesson One: The 9/11 wars aren’t over.

Twenty-two years later, the United States is still fighting a “global war on terror.” Washington abandoned George W. Bush’s “GWOT” slogan more than a decade ago under the Obama administration—and media attention has long turned elsewhere. Still, American forces remain engaged in “counterterrorism” combat across Africa and the Middle East.

In August alone, according to U.S. Central Command, American forces carried out 36 “operations” against ISIS in Iraq and Syria. So far this year, the U.S. has executed more than a dozen airstrikes against al-Shabaab in Somalia.

Fighting terrorism remains Washington’s primary justification for using military force across the globe.

Lesson Two: Their legacy is an open wound across the planet.

Outside of the United States, for hundreds of millions of people across the world, the 9/11 wars endure. The suffering, both physical and psychological, caused by American interventions in dozens of countries in the name of fighting terrorism continues.

Experts at the Costs of War Project at Brown University estimate that “3.6-3.8 million people have died indirectly in post-9/11 war zones, bringing the total death toll to at least 4.5-4.7 million and counting.”

They have also concluded that this fighting directly claimed the lives of over 432,000 civilians. That figure is the equivalent of 144 times the number of those killed on September 11.

This violence has displaced another 38 million people, fueling a global refugee crisis. Yet proponents of militarizing borders in Europe and the U.S.-Mexico frontier have willfully ignored this reality.

Lesson Three: Nobody is being held accountable.

Impunity is the universal standard of counterterrorism. Civilian victims of torture and drone strikes in at least half a dozen countries are still waiting for justice.

The architects of the 9/11 wars have been largely unconstrained by law. Authorities responsible for torture and civilian killings have not only not faced prosecution. In most cases, the most senior officials have parlayed their wartime roles into prestigious and lucrative positions in the corporate, academic, and thinktank worlds.

Ex-CIA chiefs, in particular. have enjoyed a golden escalator ride: George Tenet has served on defense contractor and other boards and is a professor at Georgetown University; Michael Hayden sits on numerous boards, including a Washington-based think tank, and teaches at George Mason University; Leon Panetta has his own institute and serves on various boards, Blue Shield of California and Oracle among them; David Petraeus works for a global investment firm and comments on contemporary affairs—and has recently been named Kissinger Senior Fellow at Yale University’s Jackson School of Global Affairs; John Brennan consults and advises numerous corporate entities and is affiliated with Fordham University and the University of Texas at Austin; and Mike Pompeo founded a political action committee and works for a DC thinktank.

Meanwhile, to mention just one example from America’s “longest war,” the family targeted by an American drone strike during the withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021 is still waiting for the compensation the Pentagon promised them after killing 10 family members, including 7 children. Unsurprisingly, U.S. authorities chose not to punish the drone crew responsible for confusing Zemari Ahmadi and his relatives with ISIS operatives.

But this is not just a Pentagon or CIA problem. The U.S.-led 9/11 wars globalized impunity under the cover of counterterrorism.

The people of Northern Ireland, for example, know this only too well. New legislation approved in London—but opposed by all major political parties in Northern Ireland, by the European Union, and human rights organizations, will shield British soldiers from prosecution for murder and torture during the Troubles and keep secret information about the British government’s actions in Northern Ireland.

Lesson Four: The “terrorist” label is a magic wand.

British and American politicians are not the only ones to justify all kinds of actions in the name of fighting terror. Almost from its origins, the term has been used to delegitimize political opponents.

But it took on a new life across the planet after 9/11, animated by George W. Bush’s “with us or against us” rhetoric and driven by the juggernaut of American military power. From the Philippines to Saudi Arabia and Nigeria and beyond, security officials have been emboldened to suppress dissent (real and imagined) in anti-terror campaigns.

Arrests and extrajudicial killings often boost approval ratings. Fighting terrorism is also lucrative. American taxpayers have paid some $8 trillion to fund the 9/11 wars. Defense contractors have enjoyed a bonanza.

Military elites across the planet have been keen to get in on the Pentagon action as well. The U.S. security state and its private contractors train and equip security forces the world over. Counterterrorism is good for budgets. And for achieving power. As Nick Turse and his colleagues at The Intercept have shown, graduates of American counterterrorism training programs in Africa have launched at least 9 coups since 2008.

Drawing legitimacy from the post-9/11 universalization of the counterterrorist state, persecuting one’s enemies as “terrorists” has become an essential foundation of the political and social order in numerous countries.

A few illustrations from different world regions reveal a distinct pattern:

In 2020 in El Salvador, President Nayib Bukele began rounding up tens of thousands of suspected gang members. Much of the international coverage focused on these arrests as an anti-crime measure targeting the transnational criminal group MS-13. However, it is crucial to note that the Salvadoran president emphasized that those he jailed were “terrorists.”

According to Salvadoran authorities, there are currently over 69,000 “terrorists” locked up in the “Terrorism Confinement Center” (Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo) and other prisons. Human rights groups have roundly condemned the arrests and the abuse of those held at the “mega-prison.”

Yet Washington’s response is complicated by the fact that it has also charged alleged MS-13 members with providing “material support to terrorists, and narco-terrorism.”

Consider, too, Narendra Modi’s India, where official rhetoric has empowered Hindu nationalist supremacy and vilified Muslims by making blanket accusations of terrorist involvement, among other accusations. Police have used anti-terror laws to crush protests against anti-Muslim discrimination and have given license to radical groups who carry out their own brutalization and murder of Muslims. Stigmatized as “terrorists,” “traitors,” and “infiltrators,” Muslims face daily violence from the authorities as well as from everyday people who imagine themselves advancing Modi’s project by murdering his opponents.

The added magic of this particular anti-terror regime is that it wins votes—and not just in India, and not just on the right. Led by Ro Khanna (D-CA), in June the U.S. Congress rolled out the red carpet for Modi; and President Joe Biden courted the Indian prime minister during a visit in Delhi, where G20 leaders met in September. Votes, campaign donations, and geopolitical alliances all outweigh any human rights concerns about India’s 220 million Muslims.

In China, the authorities have used terrorism charges to justify the mass internment of Uyghurs and other members of Muslim Turkic communities in Xinjiang. Beginning in 2014, Beijing’s “Strike Hard Campaign against Violent Terrorism” has targeted these groups for mass arrest and confinement in camps where, according to human rights groups, security officials have subjected internees to torture, forced labor, and other forms of abuse.

Similarly, In Myanmar, from 2017, the military attempted to rationalize its genocidal campaign of murder, rape, and expulsion against the Muslim Rohingya minority as a necessary use of force against terrorists.

Examples of the use of the terrorism label to validate various forms of state violence abound. The ubiquity and persistence of this practice offers further proof of the emptiness of claims about “a rules-based international order” or of a global contest between “democracy” and “autocracy” in our world today.

Lesson Five: Counterterrorism is about religion.

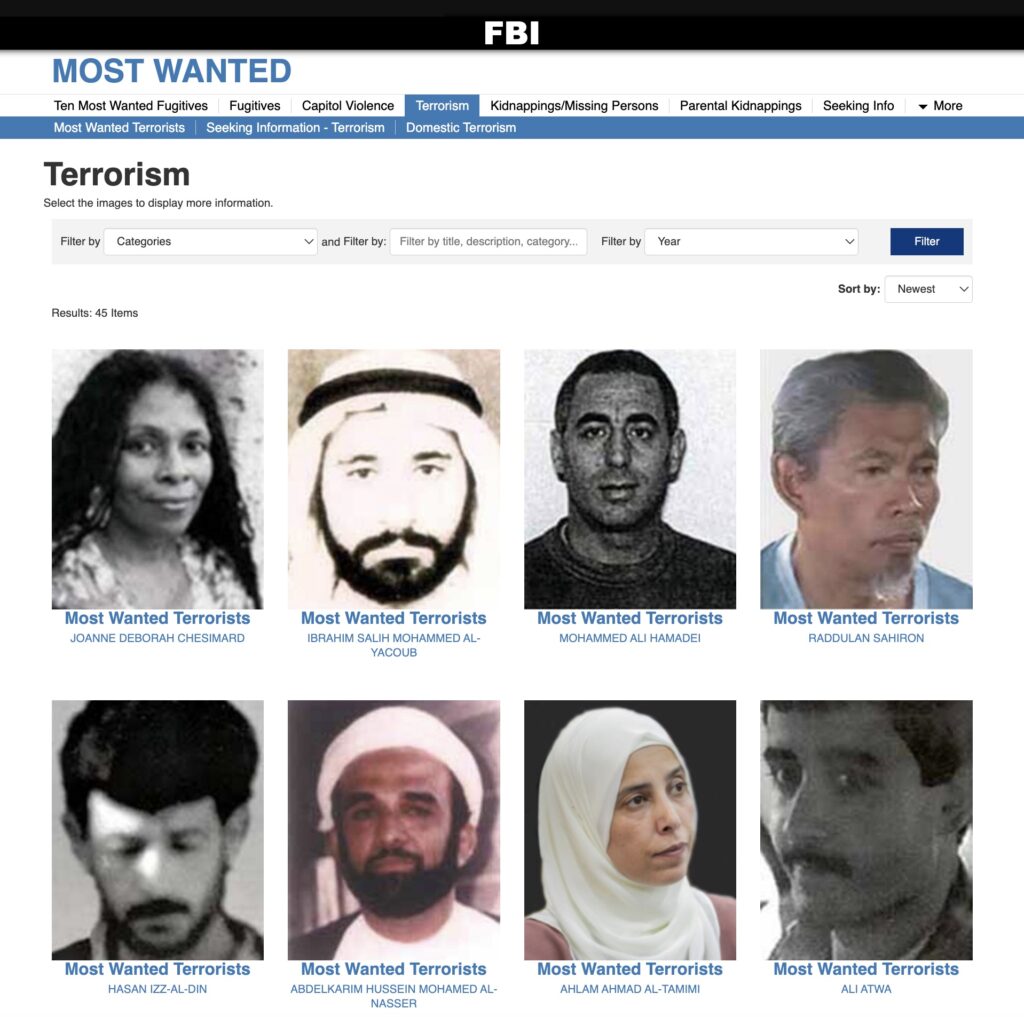

The Chinese, Indian, Myanmar, and American anti-terror regimes share a common target: Muslims. From right to left, American politicians have debated euphemisms, shuffling “terrorism” and “violent extremism” in various combinations with and without reference to Islam.

But the overarching reality is that conceptualizing terrorism is an act of imagination. And for the American security state, the terrorist they imagine is, first and foremost, a Muslim. Indeed, the idea that the Muslim is a perennial security threat to the modern nation-state has become a global idea (even in some Muslim-majority states).

Long after the reversal of President Donald Trump’s “Muslim Ban,” Muslim Americans and foreign Muslims alike are still singled out for excessive scrutiny upon entry to the U.S., and Muslim asylum-seekers are disproportionately prosecuted. The prison at Guantánamo Bay has never held a non-Muslim.

A glance at the FBI’s Most Wanted page for “terrorists” doesn’t lie:

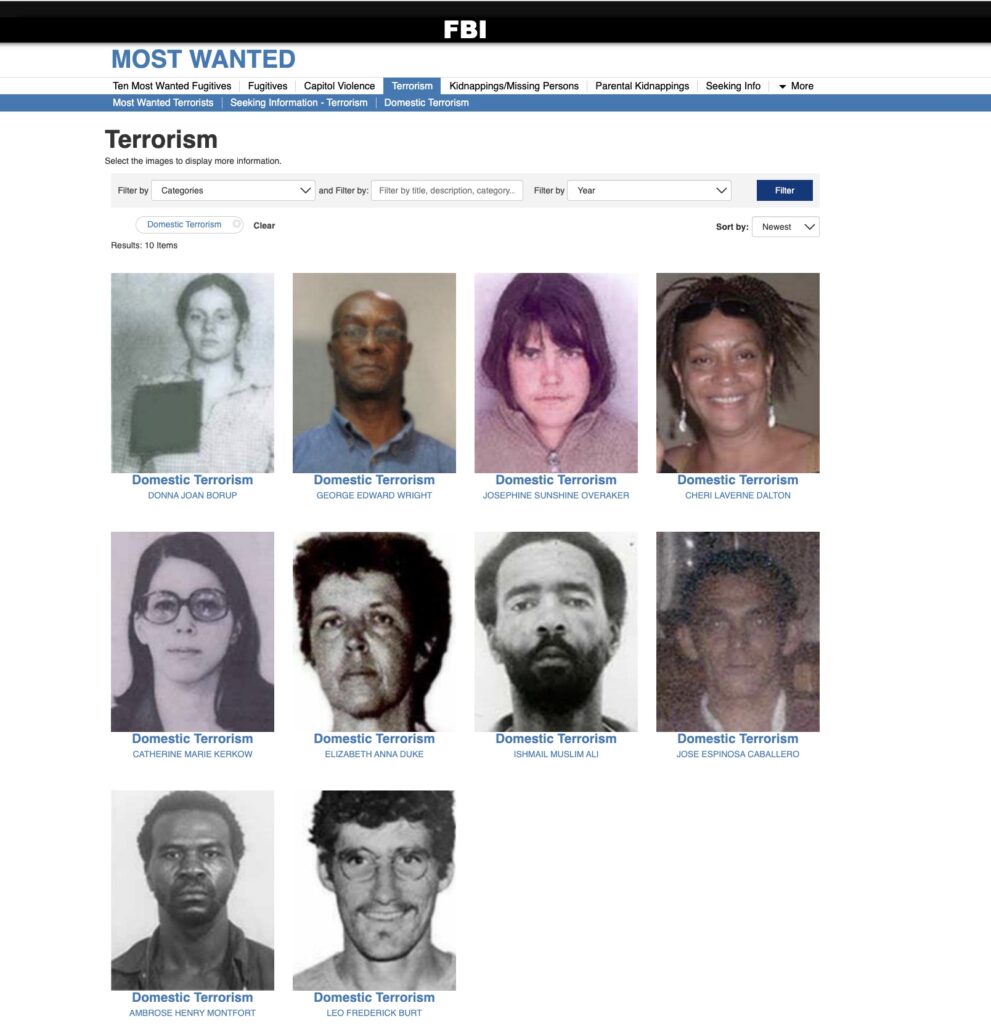

Lesson Six: … it’s also about race. But they’re looking in the wrong direction.

This is was the FBI thinks “domestic terrorists” look like:

It was only in May 2021 that the heads of U.S. Homeland Security and the Justice Department announced a “new approach” by recognizing white supremacists as the greatest challenge for American counterterrorism, though Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas and Attorney General Merrick Garland were careful to refer to “racially or ethnically motivated violent extremists”—not “terrorists.”

In this way of imagining American society, whites never terrorized enslaved Africans, Free Blacks, or Native Americans. And good white people always exercised their Second Amendment right to bear arms just to prevent tyrannical government and safeguard the domestic hearth that “Manifest Destiny” had owed them.

Thus it was not a surprise when the head of the National Counterterrorism Center, Christine Abizaid, offered a survey of the terrorism threat the U.S. confronted as of January 2023:

“In the homeland, we remain concerned about al-Qaeda and ISIS but assess that the threat they pose here is less acute than at any other time since 9/11 … In fact, the most likely threat in the United States is from lone actors, including those inspired by foreign terrorist organizations and foreign racially and ethnically motivated violent extremists (REMVEs).”

While acknowledging 17 attacks committed by white supremacists, she categorized them as “lone actors,” adding that many “were inspired by foreign REMVE attackers and their manifestos.” It is striking that the director placed the accent here on the supposedly foreign inspiration for this violence, as if the Ku Klux Klan, Proud Boys, Patriot Front and other white supremacist organizations were not homegrown political movements.

The January 6, 2021 attack on the Capitol may have been a turning point for some American elites. But the judicial system has stuck to its roots. Prosecutors have not gone after the Proud Boys and other groups that planned, organized, and carried out the assault on the Capital as “terrorists.” (An occasional terrorism-related enhancement provision added during sentencing hasn’t disrupted this pattern.)

Similarly, the mainstream conversation around white supremacist shooters continues to be about gun rights and mental health—and less about a network of men and women willing to kill and be killed in the name of a cohesive ideological program and as part of an organizational scheme that is designed to appear to be diffuse. Commentators can agree that their aim is to terrorize Black people, Latinos, Jews and others they hope to use to ignite a giant racial conflagration in the U.S. In general, though, the authorities do not formally treat them as “terrorists.”

Lesson Seven: The Counterterrorist Security State is not going to shrink itself.

Just as the Guantánamo prison has survived four U.S. presidents, the zombie-like security state isn’t going anywhere. What the U.S. spends on what it calls defense continues to rise. As Stephen Semler points out, “Donald Trump ballooned annual U.S. military spending by 20 percent in nominal terms over four years; Biden has already boosted it by 15 percent in real terms in just two.” The Department of Defense budget is soaring toward a trillion (real) dollars. The many intelligence agencies in Washington will claim nearly $100 million more.

The Transportation Security Administration (TSA) is a telling illustration of this phenomenon. Unlike special operations forces or a drone strike team, the TSA is something Americans encounter all the time. It is part of the fabric of everyday life in the U.S.—and, given the catastrophic failure of airplane security on the fateful morning of September 11, 2001, it is on the “frontlines” of fighting terrorism. Its actual capacity to detect weapons is a closely held secret, but reports of a failure rate of roughly 80% have circulated in recent years. Nonetheless, TSA workers have been tasked with rolling out an astoundingly ambitious facial recognition program in airports across the country.

Along with vast budgets, the anti-terror state vacuums up information, bulldozing privacy and civil liberties concerns in the process, in ways that only pre-2001 science fiction writers may have imagined. The nexus between Washington and Silicon Valley further risks the permanent hard-wiring of more and more invasive modes of surveillance technology.

Lesson Eight: The “terrorism” label has become a global vehicle for wielding state violence beyond any legal limits.

To invoke terrorism is to wield something magical—and mercurial. The maxim that “one man’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter” remains as true as ever, as students in any introductory class about terrorism quickly grasp. But there are other murky questions. Why should violence committed by people not wearing uniforms move us more than when a general orders a “shock and awe” bombing campaign in a gigantic city filled with civilians? When does “counterterrorism” quietly morph into “state terror?” Who decides?

In the 9/11 wars, what’s striking is the way that the invocation of terrorism has given moral license for an extraordinary range of acts of violence without accountability, compassion, or remorse on a scale that only large states can manage.

Since 9/11, counterterrorism has also had a spiraling effect: wars against terrorism in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya spawned more of the phenomenon the Americans and their allies were fighting. The war in Afghanistan dispersed the Taliban but ultimately shepherded them back to power after twenty years. The war in Iraq “succeeded” in regime change but fueled the emergence of militants across the region. ISIS was but one effect of the intervention.

Similarly, the American, French, and British war against Qaddafi removed the dictator. However, its long-term effect was to shatter Libyan society, unleash more than a decade of chaos, and scatter militants deep into African countries south and west of Libya—the same fighters later targeted as “terrorists” in operations led by the U.S., France, their African allies and, most recently, Russia.

Building upon its lethal anti-terror operations and mass killing of civilians in Syria, Moscow, too, has planted its flag as a counterterrorism force in Africa. Speaking at a United Nations conference in 2002, the head of Russia’s “National Anti-Terrorism Committee” observed that the Sahel and Maghreb “are becoming the epicenter of the Islamist terrorist threat, with the armed terrorist groups expanding their influence, and we see the danger of ISIS being reincarnated as an African caliphate.” In July of this year Russian President Vladimir Putin and the heads of 17 African states issued a declaration pledging cooperation on combating terrorism.

This last development offers another fundamental lesson about the 9/11 wars: states learn from one another, and once the language and practice of counterterrorism is in circulation, governments readily adapt.

The “terrorism” label has become a global vehicle for wielding state violence beyond any legal limits. What works for the U.S. can work for states like China, Russia, and Syria, too. For states that imagine themselves as great powers—or even regional players, there are few spatial limits either.

Moreover, fighting terrorists is popular, which is useful in places where people vote and where they do not. From Hollywood to the Hague, the figure of the terrorist as universal villain has retained broad public appeal as a target for the forces of “law and order.” In turn, politicians of various ideologies share an understanding of the utilility of “terrorism” to open up new vistas to project power.

Despite the many failures of U.S. policy since 2001, the sun hasn’t set on the manipulation of terrorism language to point American military power in new directions. For instance, recent calls to designate Mexican cartels as “foreign terrorist organizations” could pave the way for the U.S. to extend the 9/11 wars into Mexico. The counterterrorism script is, if anything, adaptable, as Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC) clearly understood when he and several Republican allies recently proposed the “Ending the Notorious, Aggressive, and Remorseless Criminal Organizations and Syndicates (NARCOS) Act”:

“They are making billions of dollars sending fentanyl and illicit drugs into the United States where it is killing our citizens by the thousands. Designating these cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations will be a game-changer. We will put the cartels in our crosshairs and go after those who provide material support to them, including the Chinese entities who send them chemicals to produce these poisons. The designation of Mexican drug cartels as FTOs is a first step in the major policy changes we need to combat this evil.”

Although these criminal organizations profit from American demand for drugs, are armed with American weapons, and are intertwined in complex ways with Mexican state institutions and politicians, Graham’s bill promises an easy fix by making fighting terrorism the “one size fits all” foreign policy weapon. At the same time, his language is a nod to the heady days after 9/11 when the American political climate was enfused with self-righteous nationalism, xenophobia, and calls for violent revenge.

But voters should not be fooled by this nostalgic smokescreen. Seeing all conflict through the lens of terrorism and counterterrorism has been a formula for spreading chaos, destruction, and misery across the planet. We should finally see through these labels to understand them as a vocabulary that legitimizes state violence everywhere—and serves the project of American global hegemony.

Robert D. Crews is Professor of History at Stanford University.