Is Civic Violence Escalating Out of Control?

Incidents of civic violence fill the headlines almost every day now. They range from school board members receiving death threats to passengers punching flight attendants to voters being intimidated at ballot drop boxes.

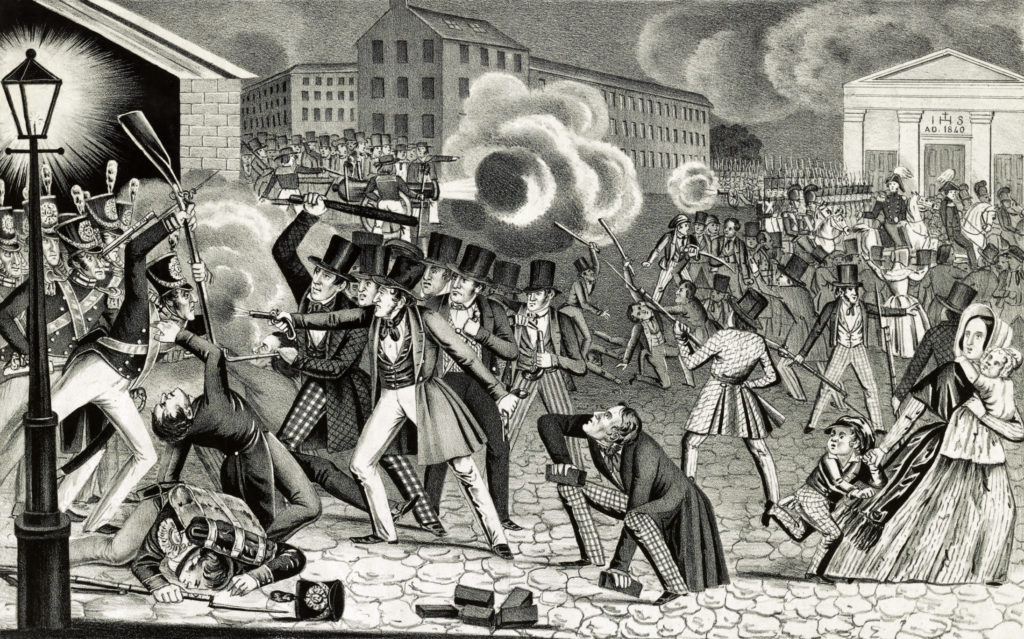

Recent articles claim that these incidents, our growing desensitization to them, and our increasing polarization and mistrust of institutionsa are tipping us toward ever more violence. Possibly civil war.

Having lived in war zones as an aid worker, I see the same trajectory. Once violence starts, people don’t just have skin in the game. They have blood. And they have lots of anger and fear, with little rationality. Conflict left unaddressed tends to escalate. More, it can be escalated unintentionally as we react to these situations without thinking. We start yelling, using derogatory language, refusing to listen to the other side.

While many people are analyzing this escalating situation, few are offering ideas of how to route ourselves away from violence and towards productive conversation. Fortunately, mechanisms already exist which we can join and promote.

Understanding the conflict escalation dynamics we’re facing

But first, we must be able to spot escalating conflict dynamics as they happen — the earlier the better. Two scenarios help demonstrate these dynamics. First is a low-level interpersonal conflict, and second a more intense political conflict.

In the first scenario, John is late meeting Tim for coffee. After 10 minutes, Tim texts John: “Are you almost here? I only have about 45 minutes.” He hears nothing. After another 10 minutes, John finally arrives, sits down, and launches into a story about his run that morning. He doesn’t apologize or explain his tardiness.

Tim starts to fume quietly, recalling similar situations. John is often late. And he often doesn’t return Tim’s calls. Now that he thinks about it, John hasn’t picked up a check in a while, either. Really, John’s being downright disrespectful, Tim thinks, as he makes mental plans to tell their mutual friend Mary that it might be time to stop seeing “Slacker John” so much. John, for his part, is embarrassed that he was late. He feels inane describing his run, but doesn’t want to talk about how his job has been threatened by an impending round of layoffs. He fears Tim will give him a lot of unsolicited advice and doesn’t have bandwidth to hear it.

In the second scenario, a diverse crowd of protesters gathers in a city square the day after a local police officer shot an unarmed man. They’re shocked and angry, carrying signs and shouting slogans – even some very anti-police slogans – but they are being non-violent. The crowd grows. Police start to form a tight line across the street. Protesters note this change, and feel the police are constricting their space. “Pigs!” they start to yell. The police call for backup.

As in both of these scenarios, conflicts start off about one issue or incident, such as someone being late to a meeting, or people objecting to a specific event. As conflict begins to escalate, intertwining dynamics take shape:

· Entrenched perceptions. We become increasingly convinced that we are right, and less able to see how our own behaviors create a response in the other. Tim starts thinking about how disrespectful John is, and John about Tim’s officiousness. The protesters see the police as impinging on their rights; the police fear violence from the growing crowd.

· Emotions take over. We start to lose the ability to think rationally. We tend to fall back on default stress behaviors we learned as children – which for most of us are not particularly constructive. Tim starts to fume. The protesters resort to name-calling, particularly dehumanizing language.

· Communication decreases. This also provokes a refusal to think – let alone converse – about how the other person or side is thinking about the situation. We do not know, nor care about, what is causing their reaction, even though that may be the key to de-escalating and possibly resolving the situation. Tim doesn’t ask John why he was late. Police may not offer assurances that they uphold the protesters’ right to peaceful protest.

· Bones of contention and parties proliferate. What started out as a conflict around one issue metastasizes to include others. We pull in allies, increasing the number of people involved. Tim enlists Mary. Police on site involve more officers or other agencies.

· Parties start to change structurally. As one side starts to use stronger tactics, the other side may actually change structurally in response. The other side may change how it thinks, how it communicates, or how it organizes. A recent example is the recent U.S. military training course that referred to protesters and journalists as “adversaries,” a departure from previous, less conflictual, terminology. Protesters treated as “adversaries” may feel pushed to respond as such, taking up stronger tactics themselves.

Happily, once we understand how conflict sparks, flares, and then rages, we can determine how to bring it under control to have constructive conversations worthy of a democracy. Doing this involves changes in our own behavior, our community relations, and national systems.

How to change our own behavior

· Train ourselves to ask “what is another story that could be told about this incident? How would the other side say we arrived at this situation?” In a pluralistic, democratic society, we must develop the skill of listening to and understanding – though not necessarily accepting – other points of view.

· Actively seek out different sources of information, as well as the backstories of events. This doesn’t need to be across the political divide, but can be with people from different professions, parts of the country, age groups. The point is to practice developing a more complicated, nuanced view of the world.

· Commit to not posting inflammatory material on social media. We all enjoy liking a tweet or post that expresses how we see the situation, and often the stronger the terms the better. But beware confirmation bias – our built-in tendency to accept information that confirms how we already see the world and ignore challenging information. This hardwiring often prompts us to accept and spread hyperbolic soundbites or even disinformation which worsen the situation.

· Uphold norms of nonviolence. We should not condone the use of violence or calls for civilians to use arms. Nor should we condone language that incites to violence. This includes terms that dehumanize, like labeling of opponents as cockroaches (deemed inciting hate speech in the Rwandan genocide) or animals (ditto in the former Yugoslavia).

How to change our communities

· Seek out groups that are diverse. In conflict zones, when violence hits, the ones who are able to avert crises are the professional associations and formalized social groups such as sports or theater clubs that have representatives of all sides of a conflict. They have the credibility and contacts to learn the facts behind a murky situation, share them publicly, and foster nonviolent solutions.

· Create space for broad, well-moderated civic dialogue. Talking across divides is difficult and requires skill but is necessary. Mayors, church leaders, universities, and others can convene town halls around community issues with a cross-section of respected speakers from different sides of a conflict. However, it is important to have experienced facilitators direct conversation in ways that create constructive dialogue rather than a frenzy of opinions and attacks.

· Promote mechanisms that enable entire communities to resolve their problems, and to do so at early stages before attitudes harden. Community mediation centers offer one such mechanism, helping to resolve a variety of issues. These range from assisting clashing neighbors to talk, to fostering mutually agreed solutions between juvenile offenders and victims which keep young people from prison for minor offenses, to preventing evictions by mediating between landlords and tenants around phased payment of rent and other options.

How to change the systems around us

· Invest in a variety of ways to address conflict. For example, most community mediation centers are run on shoestring budgets and powered by volunteers, while budgets for police departments have soared, particularly with the purchase of military equipment. Multiple studies have shown this trend reduces crime but increases use of force by police against citizens. Press for investment in community peacebuilding programs that take a holistic, relationship-building approach to conflicts.

· Create mobile crisis response units that include not just law enforcement, but also social workers, mediators, and people trained in de-escalation techniques. The Rochester NY case of a mentally ill man killed by police prompted the mayor to increase the engagement of mental health professionals in policing issues. More recently, Dayton Ohio set up a now highly-successful Mediation Response Unit to send trained mediators, rather than police, to handle neighbor and community disputes.

· Use our democratic institutions. These are the ultimate form of nonviolent conflict resolution. Enable and protect peaceful protest, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and above all enfranchisement – easy voter registration and safe, accessible voting. This year more than ever, it means not taking matters into our own hands by civilians bringing arms to a tense situation.

The good news is that none of this needs to be invented. We have much to build on. Unlike other places I’ve worked, the U.S. has an unusually strong civic spirit. We are permeated with the belief that citizens can and should play a substantive role in our democracy. As conflict intensifies in our country, hundreds of grassroots initiatives have sprung up to tackle it, from Red-Blue dialogue forums to voter education campaigns.

We have many tools. We need to use all of them.