Is Russia the Last Empire?

What we call Russia may seem remote from the innumerable challenges of day-to-day existence for millions of Ukrainians. Having endured more than a year of cruel attacks on hospitals, schools, and power stations, they are focused on surviving under the constant threat of being terrorized and murdered by an invading army. According to the UN, the Russian invasion has already claimed the lives of at least 8,000 Ukrainians and displaced some 14 million more.

Whatever label we apply to Russia’s political system, it may bring little comfort to the families of loved ones slaughtered by Russian soldiers and discarded in mass graves in Bucha, Izium, and many other places.

Still, empire has emerged as a crucial keyword in competing narratives crafted to make sense of Russia’s aggression. For Washington and Brussels, it has become an emotive reference point to explain to a divided American public and a reluctant Europe why they must confront Russia in Ukraine.

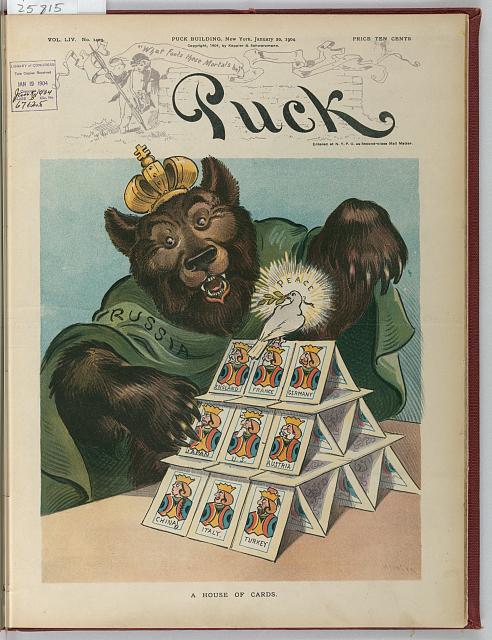

Ronald Reagan popularized the idea of the USSR as an “evil empire” in 1983 in a speech to American Evangelicals. However, today, in Kyiv, Washington, and the capitals of Europe, pundits and politicians have expanded its meaning.

Seen through this lens of empire, Russia is not merely to be condemned for its actions in Ukraine. Standing outside of the international order, it can only be defeated, or in the view of several influential observers, destroyed.

Crucially, this framing of Russia as empire assigns “the West” the task of countering any Russian imperial project. Since Russia’s invasion of February 2022, numerous commentators have reworked the idea that Russia is the last empire on the planet to mobilize support in the U.S. and Europe for a struggle that extends beyond Ukraine.

Whose Messianic Mission?

For the Yale historian Tim Snyder, Ukrainians are doing far more than waging a war of self-defense. In Foreign Affairs, Snyder argued that Ukrainians are heroically waging a war against the universal idea of empire in defense of the values of freedom and national self-determination: “Ukrainian resistance reminds us that democracy is about human risk and human principles, and a Ukrainian victory would give democracy a fresh wind.” Western officials have argued along similar lines, insisting that the Ukrainians are, in the end, advancing American and European strategic interests and values by defeating Russia. Anne Appelbaum has put her own spin on the moment, concluding “the empire must die” (drawing on the title of a recent book by the Russian writer Mikhail Zygar).

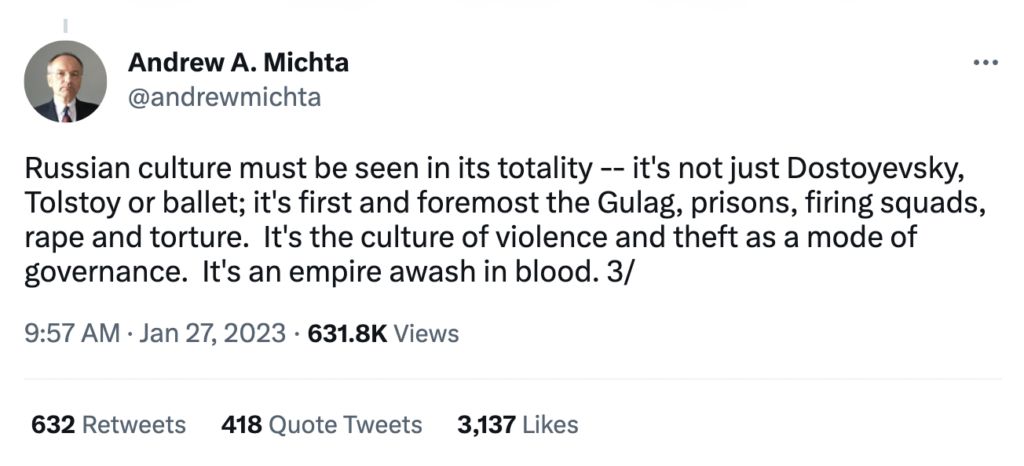

The idea that Russia is destined, by history, tradition, culture and, for some commentators, by its very genetic makeup, to menace its neighbors with imperial aggression carries important implications for considering how the world should respond. In one extreme, but not unrepresentative, formulation, Andrew A. Michta, a fellow of the influential Atlantic Council, declared that “Russian culture” is “an empire awash in blood.”

If Russia is irredeemably imperialist and despotic for now and forever, it follows that the actions of other states—whether the U.S., NATO, or Ukraine—are irrelevant in considering the path to conflict. In a January 2023 Washington Post essay rejecting negotiations and calling for “a dramatic increase” in military aid, Condoleezza Rice and Robert M. Gates claimed that Putin “believes it is his historical destiny — his messianic mission — to reestablish the Russian Empire and, as Zbigniew Brzezinski observed years ago, there can be no Russian Empire without Ukraine.”

And if Putin is driven by a “messianic mission,” we don’t need to ask why he chose to invade Ukraine in 2022, and not earlier in his twenty-plus years in power. Any serious efforts Kyiv or Washington could have pursued to avoid the war in 2021 by dealing with Moscow would have been senseless. This would include, for instance, the implementation of the French-brokered Minsk protocols whose purpose was to regulate the conflict between the Ukrainian government and Russian-supported separatists and opponents in eastern Ukraine. From a strategic point of view, there would appear to be no room for compromise with an imperialistic foe hardwired to subjugate its neighbors. Negotiations would be pointless, even foolish.

There is confusion among proponents of this position about whether Russia is currently an empire or one in-the-making. But the policy recommendations remain the same. Meanwhile, a confident air of inevitability is another essential feature of this notion: “Empires fall: The Russian empire fell, the Soviet empire fell, and sooner or later Putin’s new Russian empire will fall too.” The claim has become a social media trope.

Framing Russia as the last empire, one that must be destroyed, has created a powerful narrative. The U.S. Congress has provided Ukraine with more than $113 billion in aid since Moscow began the war. But that’s not all. The Pentagon has also shared sensitive intelligence that has allowed Kyiv to hit Russian targets, including lethal strikes on senior commanders. Moreover in early February, the Washington Post reported on a Defense Department plan that would direct U.S. Special Operations forces, presumably on Ukrainian territory or nearby, to employ Ukrainian “surrogates” against Russian targets.

Charging Russia with the offense of empire is one way to express solidarity with Ukrainians under fire—and Russia certainly fits the criteria of some of the more useful scholarly definitions of the concept. To paraphrase the historian Dominic Lieven, Russia is a “very great power” with the ambition and capacity to project power beyond its borders and influence international politics. Russia’s intervention in Syria, which began in 2015, surely distinguishes it as a kind of imperial power. Furthermore, Russia is a complex state ruling over a diverse population through varied administrative means, and its government is authoritarian.

But the framing of the conflict as simply a war of imperial conquest distorts more than it reveals about Russian—and global—politics. One can—and must—condemn Russian aggression in Ukraine. But zeroing in on Russia as the last remaining empire compromises the analytical value of the term and risks becoming just a rhetorical gesture by denying the persistence of empire as an enduring and universal state form.

A Post-Imperial World?

Crucially, the notion that Russia is a fundamentally different kind of state—an imperial anomaly in a post-imperial world—hinges on the idea of American exceptionalism. By this logic, though American power extends across the globe with no military equal on the horizon, it remains fundamentally benign, even anti-imperial in the context of Eastern Europe.

As the public conversation about the twenty-year anniversary of the American invasion and destruction of Iraq shows, the contention that Washington’s global aspirations are innately well-intentioned, and thus beyond reproach, remains a pillar of mainstream American foreign policy thinking. The denial that the U.S., too, might act as a kind of empire remains an establishment doctrine. This neglect has blinded policymakers to a more nuanced and better-informed understanding of the conduct of states such as Russia and China. Russian violence against Ukrainians is by any measure amoral and wrong, but ignoring the actual state of global politics will not hasten a Ukrainian victory or bring peace.

Russia can be fruitfully understood and critiqued as an empire. But we’ll never understand the actions of the Kremlin by treating it as the last empire operating as a rogue state outside of a “rules-based international order.” Russia is not a world apart; and the horrible violence that Russian forces have visited upon Ukraine have not taken place in a geopolitical vacuum.

It is part of an interactive global system in which states learn from and react to one another.

Consider the tragedy of Chechnya. The Russian subjugation of Chechnya—and the pitiless destruction of Grozny in particular—have appeared again and again in commentary portraying Putin as hell-bent on restoring the tsarist empire and offering proof of a uniquely Russian way of war. However, consideration of the context in which Moscow acted in Chechnya complicates this interpretation. It bears emphasizing that Russian leaders committed atrocities there with the knowledge that they had the tacit support of the international system and its most important pillar in the United States.

What is often forgotten today in the context of Russia’s assault on Ukraine is that in December 1994 when Boris Yeltsin sent troops to quash the Chechen separatist movement, he enjoyed significant international sympathy. Within days of the invasion, which ended a four-year period of the Kremlin mostly ignoring the autonomous republic, the New York Times editorial page was quick to conclude that “Mr. Yeltsin is justified in using military force to suppress the rebellion.” The editorial argued that “Chechens have an unsavory reputation” among Russians, adding “some of it the result of Russian racism, some of it deserved.” The NYT editors concluded, moreover, that the head of the Chechen separatist movement, Dzhokhar Dudaev, was little more than a “tinhorn kleptocrat that wrested leadership from genuine Chechen nationalists and is now seizing the spoils.”

The Clinton administration downplayed Russian atrocities in Chechnya at a moment when the U.S. had extraordinary financial and diplomatic leverage over Yeltsin. As recently declassified documents show, Clinton’s focus was on securing the Soviet nuclear stockpile and pushing “market reforms.” The White House also tried to force Yeltsin to accept NATO expansion over his protests about Russian “humiliation” and a lopsided post-Cold War world in which the East Bloc was gone, but NATO remained. Visiting Moscow in 1995 for a World War II Victory Day celebration and talks with the Russian president, Clinton did not raise Chechnya as an obstacle to Russian-American cooperation; and in a private meeting with opposition leaders at the U.S. embassy who critiqued Yeltsin’s approach to Chechnya, Clinton offered no response.

None of these details are meant to minimize Russia’s crimes in Chechnya or to diminish the suffering of civilians there. Rather, it is to remind us that the U.S. and Europe largely accepted the Kremlin’s framing of the conflict. In elevating the language of national sovereignty and justifying brute military force, numerous parties created an ideological framework justifying the massacre of civilians.

Russian brutality in Syria followed an analogous logic. Following September 11, 2001, American policy created a far-reaching precedent that has shaped the course of global history over the past twenty years. Washington’s insistence that states can legitimately wage their own “war on terror” against particular populations across the planet—and without any legal restraints—gave cover for other states to pursue similar policies.

The policies of Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama went beyond affording the Kremlin latitude both in the North Caucasus and in Syria. Backed by expanding technologies of state surveillance and bolstered by compliant media and entertainment institutions, counter-terrorism policies became highly mobile and adaptive frameworks for detention, rendition, the suspension of human rights and civil liberties, torture, and assassination, among other forms of state violence.

In 2015, Putin’s justification for intervention in Syria drew directly from the script that Bush and Obama had applied in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Speaking at the Valdai Conference in October 2015, Putin asserted that Russian forces were in Syria on legitimate and legal grounds at the request of the Syrian government: to defeat “terrorists,” in defense of Syrians and Russians alike.

Importantly, Putin identified “counter-terrorism” as an arena in which Moscow and Washington had interests in common. Proposing closer cooperation, he expressed regret that previous efforts in the early 2000s had not yielded greater results. Yet Putin also complained that “over the past quarter century the threshold for the use of force has been lowered considerably” and that Western sanctions policies capriciously treated some states as “vassals.” Moreover, he accused Washington of hypocrisy in Syria, pointing to its support for anti-Assad resistance groups linked to al-Qaida. The Americans, he charged, were “announcing a fight with terrorists and simultaneously trying to use some of them to arrange figures on a Middle Eastern chess board in their own interests.” “It’s wholly impossible to achieve victory over terrorism,” Putin cautioned, “if you use some of the tеrrorists as a battering ram to bring down regimes you don’t like.”

After annexing Crimea in 2014, Putin had offered similar warnings. Russia’s interests must be considered and respected, he insisted, adding that the West had crossed a line in Ukraine:

Our Western partners led by the United States of America prefer to be led in their actual politics not by international law but by the law of the strongest. They believe in their chosenness and exceptionalism, that they’re permitted to decide the fate of the world, that only they can be right.

When commenting on Ukraine, Putin’s speeches have frequently included references to his belief in the idea that Ukrainians and Russians are “one people;” however, he has also repeatedly stressed that the U.S. had dictated terms to the rest of the world for too long. As he emphasized in his post-Crimean speech, “Everything has its limits.”

The Fiction of a “Rules-Based International Order”

We can no longer assume that Russian elites operate in a closed system, one effectively bounded by the territories of the tsarist empire and Soviet Union. Moscow notices how other powers operate. They have drawn their own conclusions from the “global war on terror” and the steady march of U.S. military bases and weapons towards its borders. They are aware that the most powerful country in the world has over the past three decades steadily eroded and degraded the status of international law. Despite the recent issuing of an International Criminal Court arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin, Russian authorities have no real fear of the Hague, where only the citizens of small states are ever put on trial for war crimes. The writ of the ICC does not extend to Moscow or Washington. This, too, is the deceptively named “rules-based international order” of the early twenty-first century.

Russian elites have taken note that the difference between a “war of aggression” and a “preventive war” is in the eyes of the beholder in today’s world. To their defenders, the invasions of Iraq in March 2003 and Ukraine in February 2022 were both necessary actions taken for “national security” and “self-defense.”

Amid the horrors of Russian actions in Ukraine, it has become too easy to lose site of the wider context in which states have unleashed violence across the globe in the twenty-first century. Washington’s post-9/11 wars claimed the lives of nearly a million people (by a conservative estimate) and displaced some 38 million people across several continents. The Pentagon and CIA have carried out “counterterrorism” operations in some 85 countries, as the Brown University Costs of War Project has shown. Between 2001 and 2022, the U.S. Treasury spent (and commited to future spending) roughly $8 trillion dollars on wars in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

Twenty years after the launching of the U.S.’s preemptive war against Iraq, its architects have been prominent in casting Russia’s invasion as an unprecedented violation of international norms. In calling for a massive increase in military aid to Ukraine, Condoleezza Rice and Robert Gates have insisted that American security is at stake: “the United States has learned the hard way—in 1914, 1941 and 2001—that unprovoked aggression and attacks on the rule of law and the international order cannot be ignored.” For Rice and other advocates of the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq and the still ongoing “war on terror,” the “international order” is in peril only when states other than the U.S. or its allies wage war.

The notion that all other states must bend to American interests is a central feature of this conception of exceptionalism. Russian alarm about American defense spending tends to be discounted as delusional in Western media. Moscow stubbornly and irrationally refuses to see NATO as a “defensive” alliance, we hear again and again—even as the Pentagon lays claim to the entire planet as its realm of “responsibility” via its various “commands” that blanket every continent.

Meanwhile, far from being prosecuted, those responsible for the U.S. attack on Iraq “failed up,” graduating to prestigious positions at universities, think-tanks, and corporations. Neither they nor leaders of other major powers are in danger of being sent to the Hague for trial.

How Americans have framed their security have made others less secure, eroding the principles and institutions that would afford them some protection. Foundational texts guaranteeing the rights of displaced people and asylum-seekers, namely the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, lie in tatters along the southern borderlands of the European Union and the United States. The prison at Guantánamo Bay is more than twenty-one years old. Across the globe, the practice of torture has flourished and even expanded. As of March 2023, American forces are still fighting in “counter-terrorism” operations in Somalia, Iraq, and Syria, to name just the locales about which we have some unclassified information.

In his speech of February 24, 2022, Putin himself cited American “disregard for international law” as justification for his invasion: “wherever the West seeks to establish its order the results are bloody, unhealed wounds and sores breeding international terrorism and extremism.” And in asserting its power across the globe and expanding NATO against Russia despite promises to the contrary, the U.S., Putin charged, had become a hypocritical “empire of lies.”

Putin’s argument has proved unconvincing in Europe and much of North America. However, it resonates across the Global South, where numerous leaders have resisted pressures to get in line with U.S. and E.U. positions on Russia.

Empire Rules

Taking this grim landscape into account does not offer a moral figleaf for Putin’s horrific war or diminish the immense suffering of Ukrainians. But it does pose an alternative to seeing the war as wholly exceptional or as an unprecedented aberration. Invoking Neville Chamberlin and 1938 or recycling claims that this is the “worst violence in Europe since 1945” are efforts to foster amnesia about Europe’s recent past—whether in the wars that erupted with the collapse of Yugoslavia in the late 1980s or its extra-European military theaters since 1991.

Russia’s actions are indefensible, but it is essential to try to understand their logic, which our contemporary global conjuncture has done more to shape than ancient imperial legacies. Empire is part of the picture, but not in the way most commentators claim today.

Whereas Americans tend to deny their imperial identity, Western pundits who identify Russia as an empire would find broad agreement among most citizens of the Russian Federation that their history is that of an empire. In the early eighteenth century, Peter the Great embraced the term imperiia to characterize—and celebrate—his kingdom. His successors continued the practice in a variety of ways. But most Russians today would reject the notion that this imperial legacy is a bad thing. In what is now a very defensive reaction to ongoing critiques of empire, many Russians will reply that their empire was more benign than the rest.

This mythology shapes Russian popular support for Putin’s insistence on Russia’s great power status and his claims on Crimea and other parts of Ukraine. But it’s important to note, too, that this self-conception of a distinctive imperial benevolence is a sentiment shared in common with publics in the United Kingdom, Belgium, France, Germany, Holland, Denmark, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, and, of course, the United States. Battles over statues, textbooks, and the historic legacies of famines and climate change are part of a global reckoning with the contemporary legacies of empire.

In this context, the adventures of Russian Wagner group mercenaries in Libya, Mali, and elsewhere in Africa are broadly understood in Russia as Russians taking their rightful place in the sun, the plucky underdog rejoining a geopolitical game long dominated by the U.S. (and in much of Africa, France). At the same time, Russian authorities and a Russian public alike understand that the U.S. and NATO have long sought to deny Russia the capacity to project power beyond its borders—to act as a great power. And they resent Washington’s post-1991 refusal to recalibrate the U.S.-Russia relationship on a more equal footing. American generals refer to Latin America as “our ‘neighborhood’” and warn of Russian, Chinese, and Iranian interference while simultaneously denying the legitimacy of any analogous or reciprocal standing for Russia along its borders.

This observation does not imply that a Russian “sphere of influence” is morally legitimate. Ukrainians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Estonians, Poles, Finns, Swedes, and other neighboring peoples should enjoy their own sovereignty and security. The point is that the imbalance created by a single hegemon claimings its exclusive spheres of influence is a danger to all.

In this connection, the question of Ukraine’s international standing is particularly sensitive, not just for the oft-cited historical connections that Putin and other Russian nationalists have drawn, but also because Ukraine was at the center of previous efforts to weaken Russia. In both world wars, Berlin saw German-backed Ukrainian statehood as a means to break up a Russian empire. Today, Western talk of “ending” Russia has raised the stakes of the war far beyond Ukraine.

Similarly, treating Ukraine as a proving ground for American global influence risks hardening Russian intransigence. Former U.S. ambassador to Moscow and Stanford professor Michael McFaul has argued that defeating Russia would not just “send a powerful deterrent message as Chinese leader Xi Jinping calculates the costs of invading Taiwan.” It could also mean that “countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Middle East watching this war from the sidelines right now would lean more toward the U.S., not China and Russia, after a victory in Ukraine.” But it would be wrong, morally and strategically, to continue to use Ukraine as a showcase for American power while claiming the war is between empire and democracy.

What bears emphasizing in this brief historical sketch is that great powers have repeatedly placed Ukraine at the center of efforts to contain Russia and repel it from Europe. Zbigniew Brzezinski’s oft-quoted claim that there can be no Russian empire without Ukraine has had as its corollary a tragic legacy: it seems there can be no Ukraine without great powers seeking to instrumentalize it against Russia.

For now, Ukraine is trapped between Russian and American aspirations of hegemony. Ukraine’s misfortune is to be caught once again in a contest between imperial states. Ukrainians are compelled to participate in a zero-sum game in which only Russia or Ukraine can flourish.

In the absence of any clear military predominance, what remains ahead is instead the difficult project of reviving the universally binding effects of international law and institutions. Peace likely lies in difficult negotiations and in the forging of new zones of integration, rather than in the creation of exclusive clubs and dominant blocs. Accountability for war crimes should be a universal priority.

Restoring a truly rules-based international order will mean giving up on American unilateralism and the compulsion to dominate by force, impulses at the historic heart of empires across time and space. Decolonization, if it is to mean anything at all, is a more extensive project than its recent advocates have tended to acknowledge when directing their critique against Russia alone. The tragedy of Ukraine shows how American hegemony is simultaneously a source of insecurity. Mounting an aggressive military alliance over thirty years against Moscow steadily increased the likelihood of conflict and ultimately failed to contain Russia or deter it from attacking its neighbor. It’s time to try something different before an unjust and unnecessary war claims even more innocent lives.