Shattering the Russian Colossus

Should the West "Decolonize" Russia?

Horrific images of the Russian destruction of Ukrainian cities and villages have been broadcast across the globe for over a year. Stunning photographs and video have documented freshly dug mounds of earth bearing the collective remains of Ukrainians executed by Russian soldiers. Blood stains and children’s remains scattered on city sidewalks have offered grotesque testimony to the brutality of the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Despite this vivid imagery, managing public perception of the war has been a priority for all sides. The Kremlin has offered a jumble of justifications for the invasion. Russian soldiers are supposedly “denazifying” Ukraine. Moscow also insists that Russians are fighting Ukrainians because the latter won’t admit that they are actually Russians (living on “Russian soil” at that).

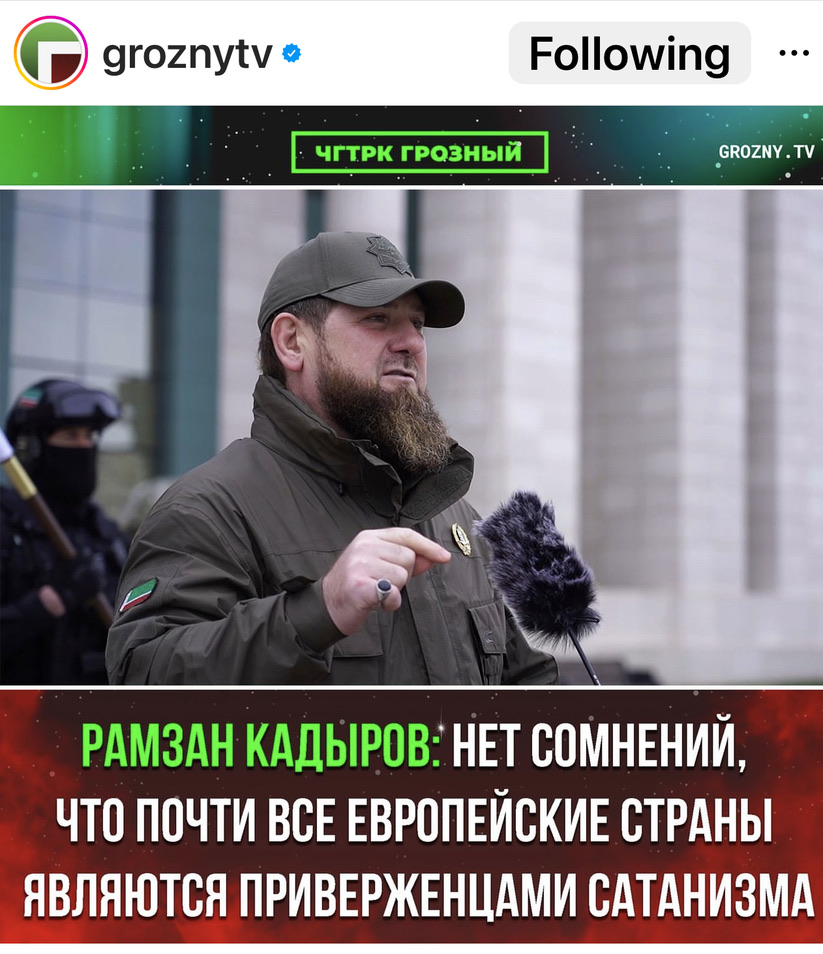

At the same time, Moscow contends, Russian missile strikes on civilian infrastructure in Kyiv and elsewhere are defending the Fatherland from NATO expansionism. And if one listens to Putin’s many surrogates, Russians are locked in existential combat with Satanists, atheists, homosexuals, and other supposed deviants who seek to corrupt pure Russian values. The war is a struggle to unify a single Slavic “people” under the Orthodox cross—and simultaneously, one learns from the senior official Muslim cleric of Chechnya, a “jihad.”

In Kyiv and the West, the Ukrainian government and its allies have offered more disciplined messaging. Ukrainians are defending their country from naked aggression. By many accounts, they are also on the frontlines of a global war for democracy and freedom—and against the tyranny of empire. In draining Russia and the forces of autocracy, they are advancing the strategic interests and values of “the West.”

An extension of such thinking is that Russia’s status as an empire must itself be confronted. Writing in The Atlantic in May 2022, Casey Michel called for the “decolonization” of Russia and the liberation of its non-Russian ethnic groups. “Once Ukraine staves off Russia’s attempt to recolonize it,” Michel urged, “the West must support full freedom for Russia’s imperial subjects.”

Despite not spelling out what such a project would look like in practical terms—or offering any evidence that these populations would welcome “liberation,” the article generated tremendous enthusiasm on social media. Activists and foreign policy commentators took up its call to decolonize Russia. The Association for Slavic, East European, & Eurasian Studies, the largest U.S.-based professional organization of scholars of the region, even decided to dedicate its next conference to the theme. Others, like Anne Applebaum, have declared that “the empire must die.”

Dismantling the Russian Empire

The idea that Russia should be not just defeated in Ukraine but destroyed as an imperial power has emerged as an influential critique of Russia’s war in Ukraine. But the aspiration long predates this conflict. Advocates of dismantling Russia have revived the notion that the country is, to quote the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin’s early twentieth-century formulation, a “prison-house of peoples.” Of course, this was the view of many a nineteenth-century nationalist. Some intellectuals in the Russian empire embraced the idea that they represented the vanguard of a distinctive nation. They struggled to realize alternatives to the empire, ranging from federation to separatism. Ukrainian nationalists, for example, mapped out various political projects envisioning a future outside the bounds of Russian autocracy and independent of other nations.

Crucially, one of the common threads unifying these aspirations across the twentieth century was their intersection with the ambitions of great powers and their plans for extinguishing the Russian empire and, later, the USSR. Today’s calls for “decolonizing” or “ending” Russia are echoes of this refrain. They were first voiced in the American context by President Woodrow Wilson, who advocated the destruction of the Russian empire and other imperial foes in the First World War. Allied empires were in practice exempt from his anti-imperialism.

The notion that Russia’s rivals could instrumentalize the grievances of non-Russian populations to bring about its disintegration found an especially eager audience in early twentieth-century Berlin. As European elites imagined how the war that erupted in 1914 might be won, imperial German authorities dreamed of “shattering the Russian colossus,” among other war aims (Fischer, 109).

Hoping to spark rebellions against the tsarist order, the German Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg commissioned leaflets for the front promising “liberation and security for the peoples subjugated by Russia.” They called for “Russian despotism to be thrown back on Moscow.” The kaiser’s generals even tried to assemble an army from among non-Russian prisoners of war held in Germany, including Muslim Tatars, to be dispatched to fight against Russia.

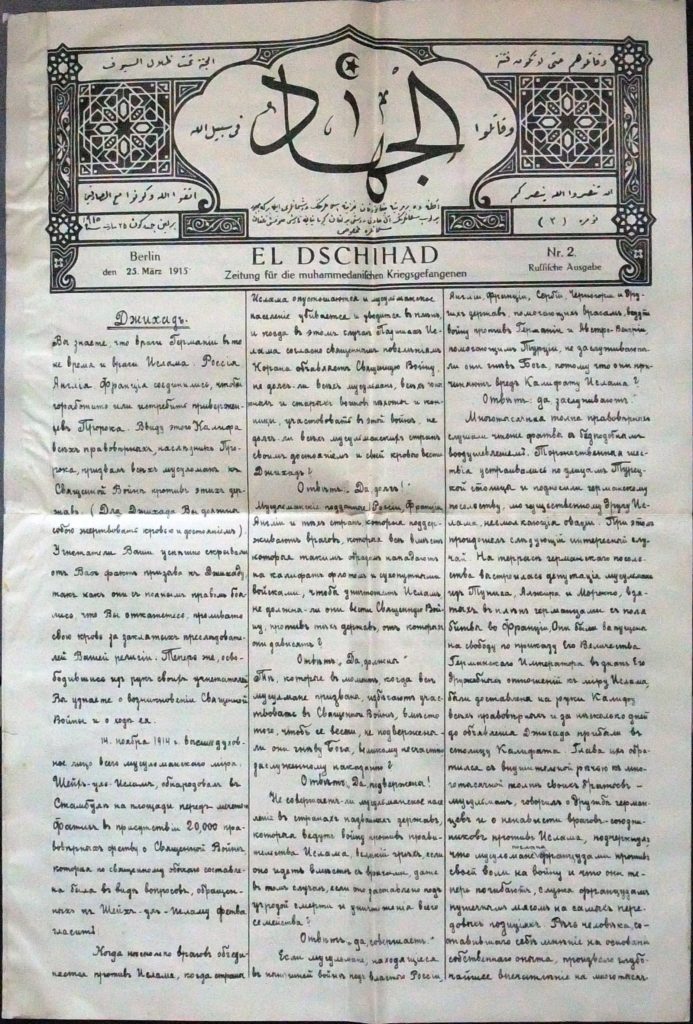

As an ally of the Ottoman sultan who had, under German pressure, declared the war a jihad, the Reich sought to turn Muslim subjects of the Russian and allied empires against their rulers. A German newspaper, Jihad (El Dschihad), translated into the many languages of the POWs, declared Russia, along with England and France, the enemy of Islam.

Beyond inciting Muslims and others to rebel, the German plan was to detach Poland, the Caucasus, and the Baltics. The establishment of an independent Ukraine was a crucial component of Berlin’s vision for the future of a German-dominated Europe.

Nations out of Empire

When German armies occupied the Western borderlands of the Russian empire, they created a space for competing groups to lay the foundations of an independent Ukrainian republic in provinces that had not recognized Ukrainian nationality as an organizing principle. Although the Germans dealt a fateful blow to the tsarist empire, Ukrainian political actors had their own, often clashing agendas. Would-be nation-builders faced enormous challenges.

Divisions between the countryside and the city were deep. A history of fraught relations among Ukrainians, Jews, Poles, and Russians was another factor. As in other periods of political turmoil, minority groups—and Jews, in particular—became targets of nationalist violence in pogroms that claimed tens of thousands of lives.

Many key Ukrainian leaders disavowed the pogroms and anti-Semitic violence. Nonetheless the idea that Jews and communists were essentially interchangeable—and thus had to be killed—endured. In January 1919, a publication of the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic asked, “In whose hands are Ukrainian lands, rivers, factories, and so on?” “In the hands of wealthy Russians, Jews, and Poles,” it offered in reply, adding, “Who always argues against an independent Ukrainian National Republic? Russians, Jews, and Poles” (Engelstein, 526). Long-standing patterns of co-existence fractured under the pressures of nationalism.

Meanwhile, the Bolsheviks, who had seized power in Petrograd in autumn 1917, possessed an army and a vision to forcefully restore tsarist territory, though on new foundations, between 1918 and 1922.

The Bolsheviks were empire-builders. But they also created conditions for the development of Ukrainian and other nationalisms, which left a deep mark on Soviet and post-Soviet politics.

Beginning in the 1920s, the Soviets had attempted to devise a way of ruling that would distinguish the USSR from what Lenin and Stalin critiqued as the “Great Russian chauvinism” of the tsarist empire. To defang nationalist intellectuals and expand their reach beyond Russian circles, the Bolsheviks tried to draw non-Russian populations into the Soviet project. They did so by creating a complex patchwork of administrative units in which members of an ethnic group recognized as the majority in that space were assigned the paramount role in state and party institutions.

By the mid-1920s, the Bolsheviks had introduced a policy of “Ukrainization,” making key concessions to Ukrainian nationalist opinion. They decreed Ukrainian the dominant language in state institutions, newspapers, and schools over the protests of many Russians, Jews, Poles and even Ukrainians. By 1930, most communist party members and state officials there identified as Ukrainian (Liber, 124).

Ukrainization encouraged identification with Ukrainian nationality on a massive scale, but Soviet policies were contradictory. Stalin’s collectivization scheme, a rush to create the USSR’s industrial base on the back of peasants, brought mass starvation to Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and other areas. Many Ukrainians remember the tragedy of the famine of 1932-1933 as a moment when Stalin singled out their people for total obliteration.

Ghosts of Berlin

The USSR itself became the target of a revitalized German vision of crushing the Russian empire in 1941. Germany’s defeat in the First World War had not dashed visions of breaking up Russia and instrumentalizing non-Russian nationalism. It is this multi-faceted problem of war-time empire that has left the greatest impact on popular consciousness, enduring as a touchstone for understanding the current war and discrediting enemies. This is true not only for Ukrainians and for Russians but for other Europeans and Americans as well.

Long a central feature of Soviet patriotism, commemoration of the war against the Nazi empire has taken on new meanings in recent years in Russia. The Putin regime has encouraged a state-centered revival of patriotic nationalism centered around the “Great Patriotic War,” nurturing a collective sense of sacrifice, heroism, and victimization.

The Kremlin’s insistence that it was forced to “denazify” Ukraine draws upon this mythology. Russian commanders tell their troops that they are fighting the same war as their forefathers. Conflating the Third Reich and Ukrainian nationalism, Moscow’s rhetoric also focuses on the historical figure Stepen Bandera (1909-1959), a Ukrainian fascist whose Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) allied itself with German occupying forces in hopes of creating an independent Ukrainian state.

In Ukraine, Bandera’s legacy is entirely different. His defenders continue to revere him, downplaying the OUN’s antisemitism and responsibility for the murder of Jews and Poles in the name of an ethnically pure Ukrainian state. A similar dissonance surrounds the Azov Brigade, a group of volunteers who organized to counter a Russian-backed separatist movement that emerged in eastern Ukraine in 2014 (and are now official members of the Ukrainian army). Self-proclaimed Nazis have been active in their ranks and among other Ukrainian right-wing political groups. Before the war Western media covered Azov fighters as dynamic architects of a violent global right. But once the Russians invaded, Western reporters shifted focus.

For its part, the Russian government has continued to play up the neo-Nazi element in Ukrainian politics. The Kremlin has stuck to its propaganda as it remains silent about Russia’s own neo-Nazi organizations and the fact that its security services have been recruiting Russian neo-Nazis to fight in Ukraine since 2014. Meanwhile, Moscow is largely silent about the Jewish identity of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy, while many Ukrainian nationalists and their allies utilize Zelenskyy’s Jewishness to ward off criticism of far-right Ukrainian actors.

Among NATO countries, too, World War II offers both a stark moral analogy and policy guide. Repeated analogies to Hitler, Churchill, and Chamberlain are used to argue that aggression and territorial expansion can only be met with armed resistance. The alliance with the USSR is left out of this picture—as is the sheer scale of loss in a multi-ethnic, German-occupied Soviet Ukraine. According to the historian Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe, some 6.85 million people died in Soviet Ukraine (of which 5.2 million were civilians), including more than 1.6 million Jews murdered by the Nazis and their local accomplices.

Given this selective recall of the war and a fuzzy understanding of its legacy in lands that bore the brunt of Nazi aggression, it is not surprising that advocates of the destruction of Russia today would unwittingly rekindle schemes originally hatched in Berlin about how to deliver a total defeat to Moscow.

Consider the proposal of Alfred Rosenberg, a leading Nazi who played a prominent role in planning the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. Rosenberg envisioned breaking up the USSR and creating in its place a group of small states that would not threaten German domination of Europe. Besides Russia, there would be a Ukraine with a capital in Kyiv and control of Crimea, plus the Baltic states, Belarus, and separate states for the Donbas, the Caucasus, and Central Asia (Luther, 36-37).

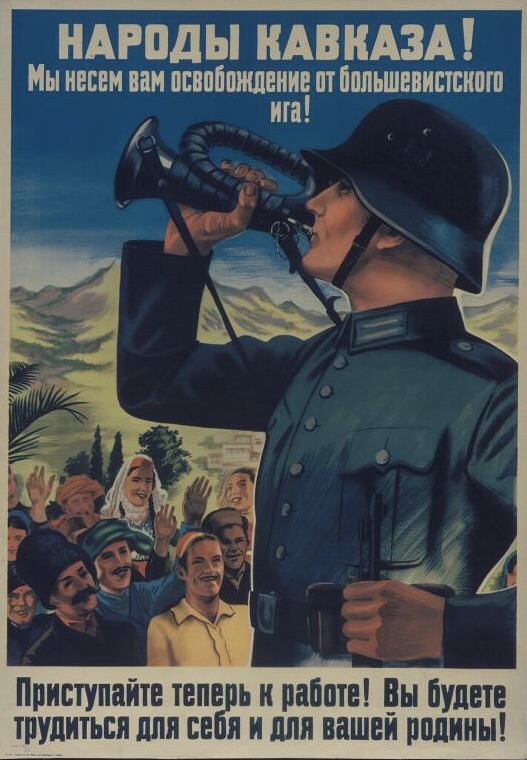

In practice, German authorities were divided about how to create Lebensraum for German colonization of Soviet territory and how to treat populations whom most German leaders viewed through the lens of Nazi racial hierarchies. One constant thread of German propaganda was to promise “liberation,” even as they murdered millions of Red Army POWs and began to kill Jews, Roma, and others they saw as political opponents.

“The German Wehrmacht has liberated you from Bolshevism and is protecting you from its return,” German authorities announced when their forces arrived in the Crimea, adding “the German people and the German Wehrmacht … are bringing you order, security, and social justice” (Luther, 44). To manage occupied territory, the Germans sought out collaborators among peoples whom they assumed could be mobilized against an oppressive Soviet state.

Hundreds of thousands of Soviet citizens colluded with or even fought alongside the Germans at various points in the war. These included Russians as well as Ukrainians and members of many other nationalities. Still, many millions more from these same groups fought in the Red Army and in underground partisan units against the Third Reich.

Hitler’s dream of razing the USSR—as the seat of what he called “Judeo-Bolshevism”—failed. But the war’s bitter legacy of victimhood and suffering lives on in the present conflict. Though Russia is obviously the aggressor, spokesmen for both countries claim their side is the victim of a replay of central aspects of the Second World War.

Fault lines generated during the war still run in multiple directions. Imagine the dilemma of the Crimean Tatars whose families Stalin deported en masse to Kazakhstan and elsewhere when the Soviets re-took the Crimea on the false charge that they had collectively sided with the Germans. For them, the Russian annexation of 2014 revived traumatic memories of decades of mistreatment from Moscow and provoked anxieties about renewed repression.

In Chechnya, by contrast, the trauma of Stalinist deportations during the Second World War has recently been adapted for other purposes. Marking the seventy-nine year anniversary of the brutal removal of Chechens and Ingush on February 23, 2023, the head of the Chechen republic Ramzan Kadyrov called the event a “horrible act of repression.” Kadyrov’s family suffered in 1944. They then fought against Moscow for Chechen independence during the 1990s. Nevertheless, today he is one of the staunchest backers of Putin’s war against Ukraine.

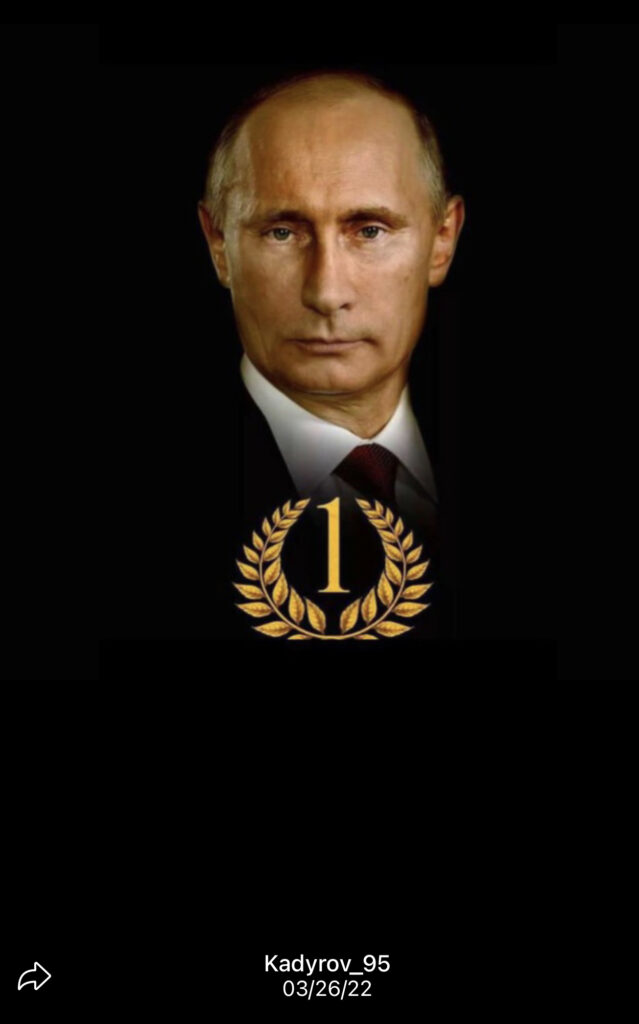

The son of a Muslim cleric and politician who went from rebel to Moscow-backed ruler of Chechnya, Kadyrov amplifies Putin’s celebration of Russian great power status. In innumerable ways, he seeks to replicate the cult of the great leader. Importantly, Kadyrov performs this loyalty by blending it with Chechen patriotism and Islamic piety. Boasting more than 3 million followers, Kadyrov’s Telegram channel (a popular messaging and social media app) features a portrait not of himself, but of Putin atop a golden garland crest emblazoned with the number “1.”

For Kadyrov, the war in Ukraine is an opportunity to position himself as a major player in Russian politics—and to complete his family’s mission to defeat his Chechen opponents. An unknown number of dissidents have taken their quest for an independent Chechnya to Ukraine. In October, the Ukrainian parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, reciprocated by recognizing the independence of Chechnya or “Ichkeria” (technically referring to it as being under “temporary occupation”).

Decolonization as Liberation?

Kadyrov—and the recent history of Chechnya—pose a dilemma for the simplistic view that the only way to support Ukraine is to dismember the Russian Federation. Kadyrov practices a form of dynastic politics that localizes the Kremlin’s political system. He embeds it in Chechen tradition, religion, and a significant measure of political autonomy. To be sure, the head of Chechnya can be likened to a cartoonish vassal of the Kremlin and a sycophantic dependent of Putin who rules his fiefdom with a crude bravado and merciless violence. His fascist-style propaganda celebrates his family, his religion, the republic, the Kremlin, and the war in Ukraine. However, he firmly controls the one territory of Russia to ever have a serious separatist movement.

Kadyrov has numerous critics, of course, but they have been forced out of Chechnya. From Europe, Turkey, and elsewhere in the Middle East, they take to social media to condemn him as a traitor to Chechnya and to Islam. Moreover, an unknown number of younger Chechens left several years ago to join the Islamic State, in effect giving the Russian government a safety valve to be rid of would-be insurgents.

As the case of Chechnya demonstrates, the absence of constituents or collaborators—however one might define them—is a fundamental challenge for any Western-sponsored project seeking to break up or decolonize Russia.

In the early 1990s, a small number of elites in Tatarstan flirted with the idea, mostly to wrest concessions from a then weak center in Moscow. Several factors prevented separatism from ever taking off: beyond the obvious fact of geography (Tatarstan, like Bashkortostan, and numerous other jurisdictions with the status of “autonomous republics” are completely enclosed by vast stretches of Russian territory), local elites learned what not to do from the Russian brutalization of Chechnya. Instead, they found a way to exercise substantial power at the local level, all while enriching themselves. Paying fealty to the Kremlin was a smaller price to pay for power and wealth, even if subordination to Moscow alienated some nationalist actors.

A Century of Decolonizing Russia

More broadly, it is crucial to acknowledge that the U.S. has already, and for a long time, had a hand in decolonizing Russia, if we use the term to mean influencing Moscow’s control over imperial territories. One could start with President Wilson’s decision to send troops to Siberia to intervene in the Russian civil war between 1918 and 1920. More relevant for our purposes is the fact that late Soviet elites made a series of decisive choices about their relationship to Mikhail Gorbachev’s faltering state based on their assumptions about how the U.S. would support them.

Recent research by Vladislav Zubok has shown how Washington was a party to the “parade of sovereignties”—the cascade of referenda and declarations of independence from the USSR. When Ukrainians, for example, learned that Washington would back the establishment of an independent state (before it was formally announced in public), they hardened their position in negotiations with Moscow about the timing and course of separation. The nature of the split deepened mistrust between numerous influential Russian and Ukrainian elites. The future of Crimea was only one of several issues that heightened hostilities.

While encouraging the splintering of the USSR, Washington firmly backed Moscow’s control over territory claimed by the Russian Federation out of fear that even more chaos would prevail. The U.S. backed Yeltsin against Chechen separatists, even when Russian forces committed mass atrocities against civilians. American support for Russian military force in North Caucasus continued into the 1990s and, after 2001, Washington and Moscow mostly saw eye to eye on taking more radical measures in the name of a “global war on terror.”

Simultaneously, throughout the 1990s, Washington’s policy was to shore up the sovereignty of former Soviet and East Bloc states against the threat of Russian revanchism even as Moscow’s military budgets and infrastructure collapsed—and over the protests of Russian elites. On the one hand, this meant the entry of numerous states into NATO (including former Soviet states Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in 2004). It also promised the integration of others (notably, in 2008, Georgia and Ukraine). After the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) led by Washington even deployed Ukrainian, Georgian, Armenian, Azerbaijani, Latvian, Estonian, and Lithuanian troops. Members of these nations had once fought in Afghanistan as soldiers in the Red Army. They now served an American-led mission.

On the other hand, Washington’s policies also meant allying with the authoritarian and repressive leadership of states in the Caucasus and Central Asia. And with far-reaching effects on regional politics. The Washington-led quest for oil and gas pipelines that would bypass Russia (and Iran) set the stage for the U.S.-backed courtship of the Taliban by several multinational energy companies. This formed a key chapter in the rise and expansion of the movement between 1994 and 1996. Beyond relationships forged around oil and gas, the search for bases and access to supply routes after 9/11 further aided the consolidation of authoritarian politics in places such as Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan.

The George W. Bush administration glossed these developments as the successful fulfilment of a “Freedom Agenda.” Washington applauded itself as the catalyst transforming states once in Moscow’s orbit. In its last days in power, the Bush White House proclaimed

Over the past eight years, the United States supported nations from

the Baltic to the Black Sea reach [sic] their goals of membership in NATO

and the European Union. The Administration supported the emergence

of democracies in Georgia and Ukraine through its support for civil society

and democratic activists during the successful Rose Revolution in Georgia

and Orange Revolution in Ukraine and continues to contribute to the

strengthening of democracy in both countries. In the wake of Russia’s

August 2008 invasion of Georgia, President Bush supported Georgia’s

sovereignty, territorial integrity, and economic recovery, including a

$1 billion economic and humanitarian support package. The

Administration helped establish Kosovo as an independent,

multi-ethnic democracy.

By 2011, Washington had a direct hand in deciding who ruled “from the Baltic to the Black Sea,” not to mention Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia, Libya, and elsewhere. Moreover, it played an essential role in the division of territory and the redrawing of maps in Europe with the emergence in 2008 of independent Kosovo—at the expense of Belgrade and its ally Moscow.

The American political elite had decided that Russia no longer mattered as a geopolitical force. All formerly Soviet states were destined for close military, economic, and political alignment with the U.S., no matter the effect on Moscow’s security—and even where popular opinion in these countries was quite divided. The powerful American Senator John McCain summed up this shift when he invited Americans to identify their futures with these states, declaring “We’re all Georgians now” in 2008, and “We’re all Ukrainians now” in 2014. That same year McCain confidently dismissed Russia as “a gas station masquerading as a country” on the Senate floor.

The Complex Realities of an Imperial Society

The dissolution of this state may be celebrated as a moment of liberation by some in the West, but few Russian citizens will welcome its collapse. The breakup of the Soviet Union and the decay of so many social welfare institutions, often pressed by actors seeking the approval of American and other foreign advisors in the 1990s, left Russian society traumatized. Economic collapse was one aspect of this lengthy period of crisis. Violence driven by ethnic and nationalist entrepreneurs was another. Even if ethnically Russian regions did not always experience first-hand the appalling fighting that accompanied Soviet disintegration in places such as Tajikistan, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Chechnya and elsewhere in the North Caucasus, they were certainly aware of the main developments and the suffering that followed. Beyond news reports, contact with refugees fleeing these regions were unavoidable reminders.

To make matters more complicated, non-Russians are not just concentrated in regions that could be detached so easily. They are also scattered across the country, with several million in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

As in Europe and the U.S., racism and discrimination are cruel facts of everyday life in Russia. The global color line runs through Russian society: groups face more racism and discrimination the further they range from “white” European archetypes. Muslims confront an Islamophobic mediascape, and most Jews must contend with a deep-seated but elusive antisemitism. Migrants and Russian citizens from Central Asia and the Caucasus find it harder to find housing and have a greater chance of suffering exploitation at work as well as abuse from the police. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the migration of tens of thousands of Russians to places like Tashkent, Bishkek, and other Central Asian cities, Central Asian comedians have had a field day commenting on how the tables have turned.

Still, like other imperial societies, Russia is complicated. Muslims, Jews, and Buddhists are formally recognized as followers of “traditional” Russian religions. Most of their leaders have cozy ties to the Kremlin. Not least, because Moscow recognizes their usefulness in preaching obedience and in burnishing Russia’s image among co-religionists abroad. In some locales, Muslim school girls are harassed for wearing hijab, while in Moscow the halal industry is flourishing, and the government is launching a significant Islamic banking pilot project.

Despite racism and discrimination, non-Russians are prominent members of Russia’s elite. Three of the businessmen on the Forbes list of top 10 billionaires in Russia in 2021 were non-Russians by ethnicity and at least nominally Muslim by religion: at number 4, Vagit Alekperov is Azeri, Alisher Usman (number 7) is Uzbek, and Suleyman Kerimov, a Lezgin, is ranked 10th. The architect of Russia’s remarkable economic buoyancy in the face of sanctions is the work of the head of the Central Bank, Elvira Nabiullina, an ethnic Tatar. In a similar fashion, Alina Zagitova and Kamila Valieva, both of Tatar background, are global ice-skating stars. Sergei Shoigu, the Minister of Defense, is from a mixed family from the Tuvan Republic in southern Siberia.

In no small part due to Shoigu’s failings, non-Russians have suffered serious casualties in the war against Ukraine, but it would be misleading to claim, as many have done, that the Kremlin is purposely treating them like cannon fodder. The Russian mobilization of fighting men has been chaotic. Yet the clear priority has been to protect the Moscow region and well-heeled and connected families. Beyond this objective, mobilization has followed overlapping lines of class and region, drawing from the most deprived areas.

As of mid-February 2023, the media outlet Mediazona has documented the deaths of 14,000 Russian servicemen in the war (though this list is not exhaustive, they acknowledge). Of these, the number of soldiers’ deaths from Tatarstan (267) are just slightly higher than those from the Moscow region (261). Fatalities in regions with substantial Muslim populations such as Bashkortostan (438) and the multi-ethnic and Muslim Dagestan (416) are higher, while Buryatia (422), with a majority population of Buryats, ranks fifth among regions with the most deaths.

However, regions where ethnic Russians predominate have, for varied geographic, economic, and other reasons, suffered comparable or even greater numbers of casualties, including Kuban (596), Ekaterinburg (523), Cheliabinsk (440), Volgograd (401), Rostov (375), Samara (317), and Perm (315).

Like ethnic Russians, non-Russians have mounted sporadic protests, and scuffles have broken out at mobilization centers; however, elites have almost universally championed the war. Russia’s leading Muslim clerics are a case in point. At an unusual gathering in March 2022, Muslim scholars from across the country met in Vladikavkaz to voice collective support for the war, characterizing it as a defensive effort with numerous precedents in Islamic history.

Their declaration asserted that Ukrainian nationalists had set out to destroy the populations of Donetsk and Luhansk, bringing “NATO with its nuclear and biological weapons to Russia’s borders, creating a direct threat to the national security of all of our country and all of our citizens.” Given the recent history of the “collective West,” which had “destroyed countries such as Iraq, Libya, and Syria,” it claimed, “a preventive strike aimed at avoiding a repeat of 1941, though now in a situation with weapons of mass destruction, is a legally and morally justified means of conducting defense policy.”

Like other citizens of Russia, these clerics confront enormous pressure to conform to the Kremlin’s line, but their reasoning offers a window onto the worldview of most members of Russian society. We might read their statement, on the one hand, as an index of state coercion and the internalization of official narratives of victimhood (note the invocation of the German invasion of 1941). On the other, it reflects antipathy toward a world in which Washington is king-maker and cartographer—and sower of chaos and destruction.

To be sure, Russian media under Putin have pushed a particular gloss on world events that has contributed to this picture. Even so, some images don’t lie. Recall video from Fallujah and Belgrade (especially of the rubble left by NATO’s targeting of civilian infrastructure). The destructive force of drone strikes that claimed the lives of civilians in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria, Libya, and elsewhere have made a deep impression and sown profound resentment over the past twenty years. One can dismiss this bitterness as a form of envy born of imperial nostalgia or as paranoia. However, a clear-eyed view would also consider the very realistic possibility that being an enemy of the U.S. entails actual danger of becoming the target of “regime change” and the chaos that has accompanied it in multiple countries since 2001.

Calling for the death of this state is understandable as a means to protest the Kremlin’s criminal policies in Ukraine. As a pledge of solidarity with Ukrainians who have suffered so much since the start of the war, it is comprehensible—but also misguided. This language only serves to reinforce the conviction that a “collective West” is out to annihilate Russians and their nuclear-armed state, one whose borders stretch across Europe and Asia. Doubling down in Ukraine would be the Kremlin’s logical–and perhaps inevitable–response.

Such rhetoric also ignores what we know about the history of this idea—and its catastrophic effects for Russians, Ukrainians, and other peoples of the region. It also dangerously ignores more immediate lessons from places such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Libya, and even Colombia and Mexico. Military force can displace particular groups from power, but it can also unleash a whirlwind of uncontrollable violence whose consequences are impossible to predict in advance.

Coming twenty years after the Bush administration launched the invasion of Iraq claiming U.S. troops would be greeted as liberators, the view that populations about whom Americans and Europeans know so little would somehow welcome “liberation” by foreigners from an evil dictator suggests how much more we have to learn about global politics.

Robert D. Crews is Professor of History at Stanford University and author of For Prophet and Tsar: Islam and Empire in Russia and Central Asia (Harvard University Press, 2006).

References

Laura Engelstein, Russia in Flames: War, Revolution, Civil War, 1914-1921 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018)

Fritz Fischer, Germany’s Aims in the First World War (NY: Norton, 1967)

George Liber, Total Wars and the Making of Modern Ukraine, 1914-1954 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016)

Michel Luther, “Die Krim unter deutscher Besatzung im zweiten Weltkrieg,” Forschungen zur Osteuropäischen Geschichte vol. 3 (1956): 28-98.

Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe, Stepan Bandera: The Life and Afterlife of a Ukrainian Nationalist (Stuttgart: ibidem, 2014)

Vladislav M. Zubok, Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021)