The Costs of Cocaine

What is the real price of the global drug trade - and who pays it?

You will hear the voice of my memories stronger than the voice of my death–that is, if death ever had a voice.

~ Juan Rulfo, Pedro Páramo

Breathing The Fire

The Colombian conflict is among the most protracted and complex armed conflicts in the world. It began as a conflict between the Colombian government in 1964 and the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), a left-wing guerrilla group. After many stalemates and failed peace processes, the Colombian government at last signed a historic–but still controversial–peace agreement with the leftist organization in November of 2016. By then, the conflict had displaced more than 6.7 million people and killed 450,000 people.

When I first arrived in Colombia in July of 2017, it was a time of real hope and possibility. At least, that’s what the media and the Colombian tourism board were leading the international community to believe.

Young and a fresh college graduate, I wanted to see the end of the world’s longest war with my own eyes. At the time, I had bought into the simple narrative I had been told: the conflict was a war between the US-backed Colombian government and the cocaine-fueled left-wing guerrilla groups. As a Mexican who had come of age during the so-called Mexican Drug War, I selfishly wanted Colombia to be an example of a country that had successfully managed to rid itself of a problem terrorizing Mexico. I wanted to believe that Latin America could eradicate drug violence without asking the United States, the world’s largest drug market, to deal with its insatiable demand for mind-altering (and numbing) drugs. Instead of finding peace, I found a conflict that was very much alive and very much misunderstood. Even years later, I cannot bring myself to look away.

Embarrassingly, I did not know that there were multiple armed groups, with distinct ideologies and approaches to violence, that had not signed the peace accords. The peace accords were exclusive to FARC and there were many other extrajudicial groups with no interest in negotiating with the government. Of these, the most egregious–and the most violent–were the right-wing paramilitary groups. With tacit support from the Colombian and American governments, they were responsible for most of the worst episodes of the conflict. Within weeks, I would come face to face with their abuse and their impunity.

But I was not only ignorant about the actors in the Colombian conflict, I was also ignorant of its underlying causes. I had not realized that cocaine was not the root cause of the violence, but rather the fuel in a fire lit by nearly three hundred years of Spanish colonization. The fire was a violent struggle over land and dignity in a country with the second most unequal and unstable system of land tenure in Latin America. It was the legacy of a colonial regime in which Spanish conquistadors were allocated vast swathes of fertile land, along with African slaves and indigenous indentured labor, to extract wealth on behalf of the Spanish Crown.

Although Colombia secured its independence from Spain in 1819, the fire their former colonizer lit endured. The descendants of the Spanish conquistadors continued to reap the wealth created by landless peasants or campesinos, many of them descendants of the African and indigenous laborers who had enriched their ancestors. Elites doubled down on their belief that campesinos were waste to justify the injustice, but trash is flammable, and the fire persisted into the 20th century. The struggle riddled the country with constant civil wars, but the fire still needed more fuel to fully explode. The fuel came in the form of cocaine.

When cocaine became a popular drug in the United States in the 1980s, drug traffickers, eager to reap and control the profits of the multi-billion business, poisoned the quest for dignity by putting Colombian campesinos under the barrel of their guns. Campesinos with tenuous land claims were easily coerced to plant coca, the crop used to manufacture cocaine. If they refused, armed groups could simply push them off land they had no legal claim to. Others would become seasonal workers on coca plantations owned by individuals affiliated with extrajudicial groups. Individuals who dared to question the shadow economy were promptly displaced, tortured, or worse, executed. If the Colombian government did respond to the campesinos’ plight they responded with military force, criminalizing them instead of putting out the fire with comprehensive land reform. In its two centuries, really five, as an elite-controlled government, it was all they knew to do. Abuse of campesinos was as integral to the government as coca was to cocaine.

As the flames of colonialism raged, violence polluted Colombia and Colombians internalized it. Its toxic fumes distorted and warped the actions and possibilities of communities over generations.

Today, in the most war-torn regions of Colombia, violence manifests itself in a multitude of ways; some subtle, others more overt. Whether it is getting into a machete duel over perceived disrespect or lying to strangers because it is easier than telling the truth, in too many parts of Colombia violence is so banal, so commonplace, that it feels impossible to distinguish from being human. And yet, there are so many who resist. Years later, I realize that peace is an action, and that peace is not made in extravagant ceremonies between government dignitaries and former militants but by ordinary people willing to say, “Ya basta.” Enough.

The Peacemaker

I met one of those ordinary people shortly after arriving in Medellin. Her name was Lucero Usma. She was a hairstylist living in an impoverished comuna or informal settlement high above the Valle de Aburrá called Manantiales de Paz (Springs of Peace) in the Medellin metropolitan area. Like so many other Colombians, she was a desplazada (displaced person), one of millions forcibly uprooted by extrajudicial armed groups.

She moved to Manantiales in 2012 after a man she was giving a haircut to was killed in her hair salon in downtown Medellin. A key witness, the gang responsible gave her twenty-four hours to flee and Lucero sought refuge where most desplazados did, up in the comunas. She left everything behind, including her three daughters. It was a shock, but it was not her first displacement; Lucero had spent over five decades on the run from the blazes of the Colombian conflict.

Once in Manantiales, she bought a plot of land from the local gang. They sold it at a discount, as the mountain where Manantiales stood had no official owner. Locals alleged that Manantiales was built on top of the ruins of Pablo Escobar’s cocaine labs and had long been abandoned until a group of desplazados founded the informal settlement in 2009.

Land in Colombia was only cheap when it wasn’t recognized by the government, putting buyers like Lucero into an impossible situation. Although she obeyed the demands of the armed group that displaced her, she was still not safe. If Lucero rubbed the new gang the wrong way, she could be evicted once again too. She knew there was nowhere to run, but there were things to do and things to say.

Lucero loved to tell stories about her encounters with Pablo Escobar or the year she spent living in the Amazon as a hairstylist for FARC in the early 2000s. Apparently, hairdressers were a prized asset for the rebel group. How else would active militants, after months of fighting the Colombian military in the jungle, exit the frontlines undetected? And like any good hairdresser, she knew everything and everyone.

With her radiant smile and rapid speech, she prided herself on giving her neighbors a measure of dignity in a place where it was so hard to feel and be human. Most of her clients were desplazados too. She felt and knew their pain. Her hair salon was a refuge where people could share their stories and mourn their past lives. Whether she was decorating her salon for Halloween and Christmas or providing free meals to those that needed them, Lucero was an integral part of her community. Lucero believed a better future was possible, and that she had an important role to play in it. She was a Spring of Peace.

Lucero desperately wanted the world to know about the human rights abuses that had taken place in Colombia and for the world to know the plight of desplazados like her. When she met me while I was helping a group of Americans do community service in Manantiales, she took me under her wing and introduced me to other desplazados in her community. She protected me from the local gang and gave me a front-row seat to the violence that was becoming ever more extreme in Colombia’s peripheries. Through her, I met Paola George and her brother, Luis Angel Perez, with whom I would spend months as a fly on the wall.

Paola, like Lucero, became my guide and took me to rural communities throughout Antioquia, the province where Medellin is located. Specifically, we worked in the northern part of the province, which has been and still is one of Colombia’s most war-torn regions. Although she was technically banned from returning to her homeland, Paola believed in telling her and her community’s story. She risked her life for that belief. Our travels and conversations with her family members and neighbors exposed me to the brutalities of the cocaine trade and the difficulties of extinguishing the fire it fueled. But in the end, it was her brother, Luis Angel, who stayed behind with Lucero, who showed me the true costs of cocaine.

The Troublemaker

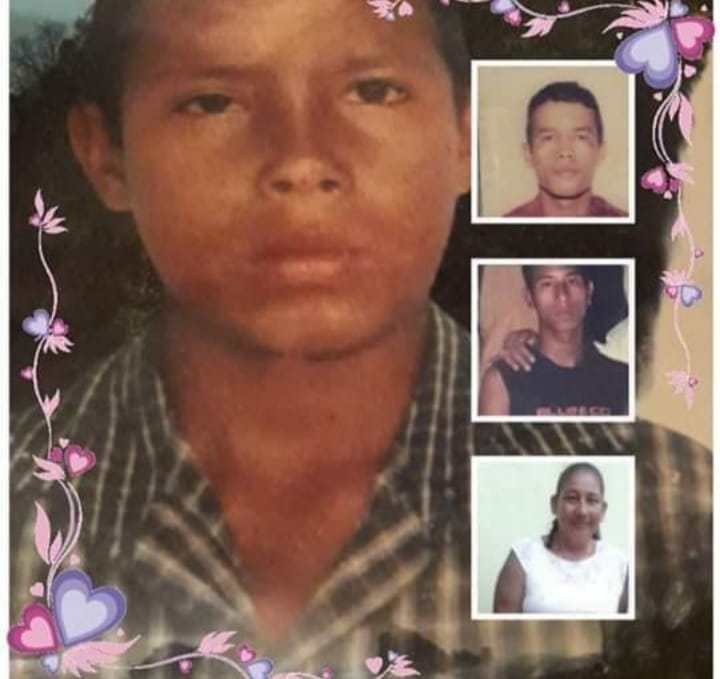

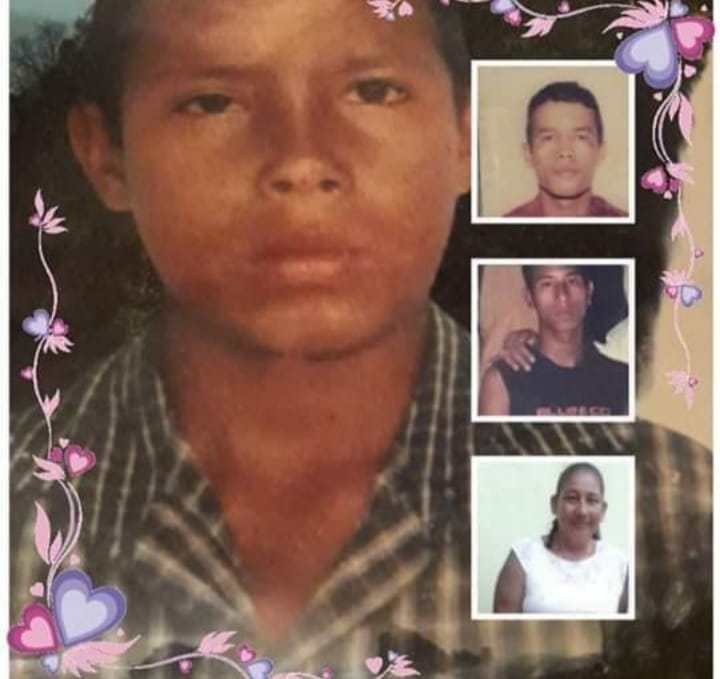

Five years after our first meeting, Luis Angel Perez Rodríguez was shot for the last time on the morning of August 31, 2022, in his hometown of Puerto Valdivia, a fishing village–and a key cocaine trafficking point on the Cauca River–four and a half hours north of Medellin.

For those who knew him, loved him, and feared him, it was not a surprise; it was a death foretold. Although Luis Angel was his name, El Mono (Blondie), as he was known, was no angel. He was frustratingly human, physically and mentally broken in more places than one.

In his thirty-one years, he had been many things: a brother, a drug addict, a raspachín (coca picker), a son, a drug trafficker, a killer, a paraplegic. Now, he was a dead man.

When he was shot, he was sitting in his wheelchair by his favorite juice stand in the El Alto neighborhood of Puerto Valdivia. El Mono was not the first person to be shot there, and he was certainly not the last. Over the years, multiple friends and family members had lost their lives sitting at the restaurants by the side of the highway that connected Medellin to the Atlantic Coast–and made life in Puerto Valdivia so lethal. For decades, different assortments of drug trafficking groups had used the road to traffic cocaine to the coast, and from the coast to its ultimate destination, the United States.

In that way, it was fitting that El Mono was killed wearing a New York Yankees shirt–a place he had never been to and now would certainly never visit. And yet, he knew New York better than most. After all, he had spent most of his life manufacturing and trafficking the drug that earned it the moniker, the city that never sleeps. Of this, El Mono had a sense. In his youth, he had used and sold cocaine for parties in Puerto Valdivia’s many bars. They were frequented by raspachines (coca pickers) and drug traffickers who come to town with extra cash to stock up before heading back into the mountains for another coca harvest.

Partying linked Puerto Valdivia and New York. Wall Street financiers used cocaine that passed through El Mono’s town to fuel late nights at the office. For them, it was a convenient stimulant that allowed them to make deals and meet quotas. But neither El Mono nor the Wall Street financiers who enriched themselves with it had a full sense of its impact.

That is perhaps cocaine’s defining characteristic: it is experienced differently in different places by different people. It is an interscalar vehicle and a metaphor for our time.

Like El Mono, Wall Street financiers certainly had a sense of the impact of cocaine. After all, as a stimulus to the grind of late-night and high-profile deals, the drug is one of the many engines of global capitalism–and the economic inequality and exploitation that are central to its function. Perhaps, their use of cocaine, their chosen fuel, is the closest they have ever come to understand their role in the global system. After all, they don’t do the drug in public. Certainly, they have heard of Narcos. Maybe some of them have even dressed up like Pablo Escobar for Halloween. But do they care? Can they care? Their use of a drug laced in blood, says otherwise. Perhaps, they explain it away like they do the costs of global capitalism, a system too complex, too intricate, to assign blame.

Although El Mono had never attended school, or even left Antioquia, the department where he was born and killed, he knew his place in the world. He knew that there were wealthy Americans eager to pay top dollar for perico (cocaine) and that he could use their money to purchase what was so elusive in his community, power.

But in a place where power and money were scarce, the competition was fierce. To have power, El Mono would have to strip it from others. Whether he called his actions, market capture is irrelevant. What is relevant is that El Mono was a part of the global capitalist system, and as a poor campesino turned drug trafficker, he had felt and carried out its worst effects.

The Fire

Although El Mono had spent most of his life in Puerto Valdivia, he was not a native son. He was from a part of Colombia where cars were replaced by mules, and where distance was measured in hours walked. He was not from the river, but from the mountains. His hometown of Filadelfia, inaccessible by car, was a twelve hour walk from Puerto Valdivia and a part of the larger vicinity of El Aro.

El Aro was a small town founded in the mid-20th century by a group of landless campesinos seeking to build a community of their own. And like El Mono, it was not only emblematic of Colombia’s struggle for a just system of land tenure, but it was also disfigured by it. Perhaps more than any other place in Colombia, its geography and history help explain why a colonial system of land tenure has persisted into the present.

Traversed by the Andes on multiple sides and with 50% of its territory covered in rainforest, Colombia had always been difficult to settle–and to unite. In its first one hundred years, Colombia saw six civil wars fought between Liberals and Conservatives over land and who had a right to claim it. Although some actors and settings changed, each war was sectarian in nature. Divisions were easy to emerge and maintain in a country where geography made it impossible for people to communicate across distance, and to therefore view themselves as one nation.

During the colonial era the Spaniards hadn’t invested much in Colombia, then a part of the Viceroyalty of New Granada. Although it was rich in gold, its gold reserves were alluvial and far away from population centers in the Andean region. Instead, Spain made most of their investments in extracting silver from mines in the viceroyalties of New Spain (Mexico) and Peru where minerals were more easily accessible and plentiful. Still, tobacco and sugar plantations emerged, and African slaves and indigenous labor were used to enrich local elites and European buyers, but they were never enough to make this long-neglected colony wealthy or a priority for the Spanish government.

Once independent, the Colombian government was faced with building an export economy to finance its development. It was wealthy in fertile land, but without prior investment, and a challenging geography, the Colombian government struggled to build infrastructure that would allow its economy to grow and its people to unite. Throughout the 19th century, the Colombian government struggled to assert control over its disparate regions. While colonial structures were kept in place, new demand for Colombian commodities emerged.

Colombia’s traditional, largely white, elite entrenched their power through the exports of coffee, sugar, bananas, and cattle, while descendants of African slaves and indigenous people, as well as poor whites, toiled on land they did not own. As Colombia integrated itself into the global capitalist system, its inequalities formed a stubborn alliance with its colonial legacy. With land as its primary source of wealth, access to land was synonymous with a dignified life. However, dignity required more than land; it also required recognition by the state. The denial of land and dignity ignited a fire, a struggle, over Colombia that has claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of people, almost all of them landless and non-white.

Throughout the 19th century and into the 20th century, elites kept expanding their landholdings, and land pressure by landless campesinos built up. Rather than implement comprehensive land reform, the Colombian government responded to land pressure with a system of land colonization. Land colonization was a land tenure system that allowed campesinos to claim unclaimed land with the stipulation they would build the infrastructure to make it productive. With most land claimed by population centers, colonization pushed landless peasants into the country’s more remote areas.

Instead of granting campesinos the dignity of land ownership, the Colombian government simply disposed of them. It was in this context that El Mono’s ancestors founded El Aro and its surrounding communities in the 1920s. Similarly, campesinos around the country sought out land to build a future, but often had to settle in areas far removed from government centers. Their distance from the state made it impossible for them to register land claims, leaving them vulnerable to land grabs and land disputes. They thought they were putting out the flames, but they were only igniting them further.

Colombia’s unequal and unstable system of land tenure reached a breaking point during a decade of turmoil known as La Violencia (1948-1958). While the assassination of Liberal presidential candidate Luis Elicier Gaitan by a Conservative in Bogota in 1948 and the resulting Bogotazo riots, which lasted ten hours and killed 5,000 people, were the ostensible triggers for the conflict, the real violence was felt in Colombia’s rural areas. Wealthy landowners–and in some cases, opportunistic campesinos–exploited political differences to seize land and exacerbate Colombia’s original sin. Once again, the blaze persisted.

To protect themselves from abusive landholders, who had created their own right-leaning militias, campesinos began forming self-defense groups to protect themselves. By the time the Liberal and Conservative parties reached a peace agreement known as the National Front in 1958, Colombia had lost 200,000 people, an astounding number in a country of 12 million.

The government’s refusal to overlook the land grabs and institute land reform led to a new internal conflict in the 1960s with left-guerrilla groups. These were successors to the campesino self-defense groups during La Violencia. They had one main demand: land reform. Of these radical organizations, FARC would become the largest and most notable.

The Colombian government faced pressure from the United States to crack down on Communist ideology within its borders. Rather than listen to left-wing guerrilla groups, in 1964 the government cracked down on its opponents. Those who survived found refuge in peripheral communities like El Aro and Puerto Valdivia, where state presence was minimal. There, they became a state of their own and began building alternative governance institutions that the state could not or would not provide.

The Waste

Left-wing guerrilla groups took on the role of local authorities, constructing roads and schools, levying taxes, and administering punishments. Justice, however, was often arbitrary and brutal, with fines, forced evictions, torture, and executions being doled out with no due process. Rumors became weapons and suspicion was cast on everyone. In this environment, it was all too easy for people to be treated as expendable. It was easy to treat others like objects when you felt like an object too.

Born in FARC territory, this was El Mono’s inheritance. His father, a notorious troublemaker, was incarcerated when El Mono was just a toddler after killing his own brother in front of his entire family. But the violence that El Mono experienced was not always so overt–child abuse was rampant, and some of his earliest memories were of being physically hit by his mother. In the end, Doralva was the only person he would ever love.

While his father was imprisoned, his older sister Paola, twelve years his senior, took charge of the family. She didn’t have much of a choice, as they were living in guerrilla territory where the state’s presence was minimal. As far as the government was concerned, they and their struggles were nothing more than a nuisance.

Paola later recalled, “The home we grew up in was made of banana leaves and sticks. Cockroaches used to eat the skin from our elbows.” The government threw them away, and because they had been discarded, they lived and felt like waste.

Assigned male at birth, and still presenting as a man, Paola found work as a field laborer, initially on the corn and rice field owned by her relatives around El Aro. When she was just eleven, she left home to work in Colombia’s burgeoning coca fields, but always returned to share her earnings with her mother and six younger siblings once the season was over. While El Aro was no utopia, Paola never imagined they would one day be forced to abandon their home.

Beginning in the 1970s, Colombia emerged as the world’s leading transit center for cocaine. Although the drug was originally produced in the Andean foothills of Bolivia and Peru, Colombian drug lords amassed vast fortunes by trafficking it northward, rather than manufacturing it themselves. The drug trade quickly became a significant industry in Colombia, elevating individuals like Pablo Escobar and the Rodríguez Orejuela brothers to billionaire status. These men became so powerful, they began to threaten the integrity of the Colombian state.

But as the government began to fight back against the Medellin and Cali cartels, the cartels turned to hiring left-wing guerrilla groups to cultivate coca and manufacture cocaine. Recognizing the potential of drug profits to strengthen their insurgency, FARC members began to manufacture cocaine on their own.

After the fall of the Medellin and Cali cartels in the mid-1990s, FARC filled the power vacuum. It became the world’s wealthiest drug trafficking organization. At one point, FARC controlled over 40% of the entire trade.

But FARC’s abuses against campesinos continued, as did their penchant for disrupting the economic activities of wealthy landowners and business owners through kidnappings and road closures. Frustrations with the government’s failure to end the insurgency led Colombian elites to form their own self-defense militias that eventually became right-wing paramilitary groups.

In 1996, these previously disparate militias united under an umbrella organization called the AUC, which was hungry for guerrilla blood and the drug profits they controlled. From 1996 to 2002 they launched a counter-offensive against FARC, marking the most violent chapter in what was already a 30-year-long civil war. This offensive would change El Mono’s life forever.

During the last week of October of 1997, when El Mono was five years old and Paola was seventeen, a paramilitary group–reportedly with the support of the Antioquia government–marched into the town square of El Aro and carried out a brutal massacre. The group murdered fifteen people, the majority of whom were merchants who traded goods with neighboring campesino communities. The merchants were accused of aiding and abetting the guerrillas. Yet, instead of standing trial, they paid for their alleged collaboration with their lives. After the killings, the paramilitary group, or paracos, as locals called them, burned down the entire town. The attack sent a chilling message: the town, its cause, and the people who lived there were disposable. Campesinos were waste, and now they had been wasted.

Although by 1997, the cocaine trade had taken off in Puerto Valdivia, in El Aro, the community had resisted the lure of the drug trade. While their lives were not perfect, they had enough food to eat and were able to sustain themselves. And yet, El Aro played a significant role in the drug trade as it served as a key entry point into El Nudo de Paramillo, a crucial mountain pass for arms and drug trafficking and a stronghold for FARC. Following the bloodshed in El Aro, the town was largely abandoned. The town and its surrounding communities fell into a deep economic depression. Within a few months, the first cocales (coca plants) began to emerge. Without any alternative means of income, El Aro residents turned to coca cultivation, as drug profits became the only viable source of sustenance for the community.

But few returned. Years later, El Aro remains burned and many of the roads that lead to it are scarcely used. The violence that had taken place was too haunting, too traumatic, to convince its once proud residents to return. El Mono’s family was one of the hundreds who took part in the exodus. They joined other victims of the massacre in settling in Puerto Valdivia, where Paola had recently bought a plot of land. The plot was too small to subsist on, but it was large enough to build a home. It was there, in Puerto Valdivia, a town of landless and land-deprived campesinos like him, where El Mono would lose most of his family.

The Fuel

Although El Aro was destroyed, the paramilitary campaign to eradicate FARC and its supporters continued into the early 2000s. Throughout Colombia, paramilitary groups continued to massacre thousands of civilians until their secretive and incomplete demobilization in 2006. Towns that were previously uncontested became battlegrounds. Meanwhile, coca production continued to rise, forcing campesinos to not only increase their interactions with armed groups but also to rely on them for their survival. In this battle for territorial control and drug profits, Puerto Valdivia served as a major stage. First, as a gateway into Antioquia’s coca country, and second, as the site of the only bridge that connected Medellin, a cocaine stockpiling and administrative hub, to the Atlantic Coast, where traffickers shipped cocaine to international markets.

The fight to control Puerto Valdivia was particularly complex, as it was waged among three rival drug-trafficking groups: right-wing paramilitary groups, FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), and ELN (National Liberation Army), another left-wing guerrilla group. It was particularly violent because its entire economy revolved around the cocaine industry. Anyone who sold mercancía, or cocaine base, to an opposing armed group could face execution.

Campesinos couldn’t sell fully processed cocaine, or powdered cocaine, as armed groups had a monopoly on the product, and its exponentially higher selling price. Instead, they sold the drug in its solid form, as cocaine base. It was exploitative, and a way to keep drug profits concentrated in the hands of drug trafficking groups. The monopoly on powdered cocaine also gave drug trafficking groups the power to purchase guns to compete and discipline disloyal campesinos.

The rub with Puerto Valdivia was that it constantly switched hands, making it impossible for any campesino to claim innocence. Every supermarket, hair salon, restaurant, and mototaxi served raspachines (coca pickers) and patrones (owners of coca plantations) who came to town to stock up or relax before heading back to the fields. As for the town itself, most of its male residents were seasonal workers on coca plantations. When the cocaine trade was booming, business was booming. But it was a double-edged sword, as more drug money meant more attention from drug trafficking groups and more deaths. Even those who did not explicitly participate in the cocaine trade were targets. Coca cultivation season ended, but it was always open season. Cocaine added new fuel to Colombia’s fire, and the violence spiraled out of control.

El Mono came of age amid the violence. People fell like the orange zapotes from the trees. Throughout his childhood, he saw multiple friends, family members, and neighbors lose their lives to causes everyone knew better than to ask why. Ver y callar, see but keep silent, was the rule of the land.

In 2001, amidst the carnage, El Mono’s father was killed. His heavy drinking and penchant for dueling had finally caught up with him. For El Mono, his father’s death was a tragedy, but for Paola, it was a relief. By then, Paola had come out as a transgender woman. While her transition was a shock–even an aberration– for many in her community, she had already gained their respect. Her devotion to her mother and siblings was far more important. But in the eyes of the man she called father, she would forever be a disappointment. “My father used to chase Paola around our neighborhood with a machete, but she never let him get her,” El Mono recalled.

With her father gone, Paola was able to spend more time at home. She retired from the fields and became a mototaxi driver. It was a welcome change because at the time work as a coca picker wasn’t as lucrative as it usually was. Under Plan Colombia, a multi-billion-dollar agreement between the Colombian and American governments, Colombia had begun an aggressive coca eradication campaign. Between 2000 and 2003, using planes and helicopters provided by the US, the Colombian government sprayed glyphosate on coca plantations. While targeted at coca plants, the chemical also destroyed campesino food and livestock supplies.

The campaign further destroyed campesino subsistence economies and pushed more of them into the underground cocaine trade once the spraying had stopped. Meanwhile, El Mono’s career in cocaine production was just beginning, as was the gradual loss of his family members. By the time he was twenty years old, he had already lost three of his siblings, all to violence and addiction.

Deeply affected by the loss of his father, El Mono began to act out. He lived for the streets and was constantly getting into trouble. He was eventually hit by a car and subsequently hospitalized for five months. According to Paola, the accident left him with brain damage further increasing his propensity for trouble. El Mono began stealing livestock and food from his neighbors. In a different setting, he might have received therapy or been placed in a special needs program. However, in a town then-controlled by paramilitaries, which had their own alternative governance structures, his habits put his life at risk. The paracos were known to be far less forgiving than FARC, and stealing was punishable by death. Unruly and unable to control him, his mother worried for his safety.

Landless, she sent him to work with relatives who owned coca plantations. He was a child, but he had hands he could use. She thought she was saving his life. Instead, she inadvertently helped write his death sentence.

Life as a raspachín was grueling. The days were long, and the work was painful. Pulling the leaves from their stems left his hands full of blisters and scratches. Despite the hardship, El Mono was good at the job, and he eventually learned to process coca leaves into a base or paste. It was a multi-step process that involved mixing coca leaves with cement, urea, gasoline, sulfuric acid, and ammonium. The process was dangerous, but so was being a raspachín. To unwind after a long day of work, El Mono’s uncle introduced him to marijuana.

He was paid three dollars a day, but he saw how his patrones were enriching themselves off his labor. Tired of scratching at drug profits, he and a group of friends decided to go their own way. In 2006, he saw an opening. The paramilitaries had gone through a secretive and controversial peace process with the government. And after a brutal military campaign against FARC under President Alvaro Uribe (2002-2010), Puerto Valdivia found itself under no one’s control. El Mono, and a group of friends, took advantage of the relative peace and formed their own gang.

They called it “La India,” after their neighborhood. For four years, they stole mercancia (cocaine base), from local farmers in the region and sold it to non-affiliated individuals who could process it into cocaine. Through his work with La India, he was able to get ahold of his first gun, a lifelong obsession. El Mono acquired it after he and his friend killed two soldiers in the Colombian military and took their guns. The power the gun gave him was exhilarating. For the first time in his life, he felt like he had control of his own destiny. How many people he killed, and how many he hurt, El Mono never said. Throughout all this, his mother made desperate attempts to get him to leave the gang, but he would not listen. He had grown up around violence: why shouldn’t he partake in it too?

The guerrilla and paramilitary groups eventually returned to Puerto Valdivia–and La India was disbanded. Due to multiple complaints against him for theft, El Mono was on the paramilitaries’ radar. He once again left Puerto Valdivia for the coca fields. This time he was hired by a distant cousin who would further fuel El Mono’s descent into violence. His cousin, in an effort to increase productivity among his workers, laced the marijuana blunts he gave them with a substance called basuco, thinking it would make them work faster. After all, workers were and needed fuel.

Derived from the Spanish word basura, or trash, basuco is the paste left at the bottom of a barrel after cocaine production. It is also a highly addictive and potent drug with toxic levels of leaded gasoline, and when smoked, it can cause brain damage. Almost immediately after trying it, El Mono was hooked. His addiction forced him to give up his job and return to Puerto Valdivia, where he resorted to stealing from passing trucks and cars to fuel his habit. Years later, El Mono recalled, “I lived under the bridge in Puerto Valdivia for a year. All I could think about was smoking basuco. All my money went to feed my addiction. I couldn’t do anything else.”

His mother agonized over her son’s addiction, but with limited financial means, rehab was not an option. On his own, El Mono was eventually able to wean himself off basuco by using marijuana. Clean, he returned to the coca fields. During his absence, his younger brother Germán, also known as Nano, fell victim to the same addiction. He, too, turned to stealing from passing vehicles to support his habit. Nano was not as lucky as his brother. Even though the paracos enriched themselves from his suffering, they executed him and his friend for stealing. They were sixteen years old, but in the eyes of their killers, they were waste, undeserving of empathy.

The Pollution

For three years, El Mono stayed away from Puerto Valdivia. He was working hard and keeping a low profile. For a moment, it seemed like he had finally turned his life around. In 2013, he returned to Puerto Valdivia to visit his mother. The decision nearly killed him.

Months earlier, he had mentioned to one of his cousins that he was going back to Puerto Valdivia to steal mercancía from one of his wealthy uncles, who was a narcotraficante (drug-trafficker). It is unclear whether the threat was real. Paola never took it seriously as El Mono often made empty threats due to effects of his year-long basuco addiction and the car accident. El Mono’s uncle was far less forgiving; he paid the paracos $600 to finally kill him.

While in the center of town to buy marijuana before going back to the coca fields, El Mono was apprehended and before he knew it, five bullets had entered his body. The shooter left thinking he was already dead. Within minutes, a crowd of neighbors gathered around him, watching helplessly as he bled out. They couldn’t rush him to the hospital. Earlier that year, the paramilitaries had mandated that only family members could pick up shot relatives. Anyone who defied their orders would be shot too.

As blood kept spilling out of his body, Paola arrived. She had lent him her motorcycle and became worried when he didn’t come home. Despite withstanding years of transphobic abuse from El Mono, he was still her brother; without hesitation, she picked him up and rushed him to the hospital. Miraculously, he survived. Later, he was taken to a special clinic in Medellin, where he and his mother were informed that one of the bullets had struck his spinal cord, leaving him paralyzed and unable to walk again.

He was the last of Paola’s immediate family members to get shot–and the lone survivor. For a time, at least. They were all counted in the casualty statistics of the Colombian conflict, but the reality was much more complex.

Although the government counted Paola’s father as a victim of the paramilitaries, he was actually killed by a neighbor with whom he had an ongoing feud. Paola’s brother, Chilo, followed in their father’s footsteps and killed their other brother, Willian, because he was gay. And, of course, German was killed by a paramilitary group for his stealing and his addiction. Out of the five shot in their family, only two were shot by a paramilitary group; of these, one was shot because a family member paid the group to execute him. While their deaths cannot be understood without the context of the wider conflict, they are indicative of something more nefarious– the internalization of violence. When waste is lit on fire, those who have been thrown away are left to breathe in its toxic fumes.

These were the foundations on which the cocaine trade was poured onto Colombia. Naturally, violence exploded and further tainted the air. Internalized violence, like polluted air, became so pervasive to the point that it is imperceptible, inseparable from the experience of being human. It was only logical that people would behave toxically. With no entity to counter the toxicity with empathy, shades of violence became the only means of expression. For El Mono–even after he could no longer move– violence was the only story he could envision for himself; it was the only story he knew.

After fourth months in Medellin, El Mono returned to Puerto Valdivia. In a wheelchair, he was no longer considered a menace, at least, for a time. As a person whose source of income and worth had been his body, his paralysis was devastating. Unable to move his hands or even read, every day felt eternal. The only thing that got him through was his mother, who faithfully took care of him. She changed his diapers, bathed, and fed him. Doralva was always there, until she wasn’t. A lifetime of loss had taken a toll on her health.

She died of a heart attack in 2015. In the ambulance to the hospital, she asked Paola to take care of him and she did, until she couldn’t. In 2016, she received a death threat from a newly invigorated ELN. As a motorcycle taxi driver, she had given many rides to paramilitary group members. It was a part of the job. But there was no negotiating to be done. From one day to the next, she was in Medellin starting a new life.

She left everything behind, including her brother. Neighbors looked after him while Paola worked on finding a new home. The process took nearly a year. In the meantime, El Mono stayed in Puerto Valdivia where he relied on the charity of his neighbors for food and diapers. Seeing his desperation, a family member allowed him to sell cocaine in the town. In charge of logistics and packing the drug, he and a group of childhood friends sold the drug throughout Puerto Valdivia. No longer a visible menace, the paramilitaries allowed him to pursue his business. But Paola worried. He had multiple friends in armed groups and was stockpiling guns. Loyal to her mother, she sent for him.

He stayed with her in Medellin for three years, until they eventually had a falling out. She sent him back to Puerto Valdivia where he was once again taken care of by neighbors and family members. Like before, he sold drugs for a living. This time, however, he was an official member of paramilitaries. His hometown was seeing yet another explosion of violence. After FARC had officially demobilized, dissident groups of the rebel group were contesting Puerto Valdivia–and ELN, which had recently broken off its peace talks with the government–was trying to seize the town. They were killing all people affiliated with the paracos. Given his frail state and his work as a look out, El Mono was an easy target. On August 31, 2022, the waste was at last disposed of.

The Wasted

When El Mono took his last breath, he had lived way past his expiration date and there was evidence of the rot everywhere. Years of disuse had corroded the muscle on his arms, leaving them as emaciated as his bones. The skin that wrapped them was adorned with tattoos of la Virgen del Carmen, good luck charms that had failed to charm. His legs, once used to run away from irate neighbors, now hung limply from the wheelchair where he spent his days. Long after his retirement from the coca fields, his hands still bore the scars of years of working one of the most dangerous jobs on the planet. The bullet–and the cause of his retirement–was still lodged in his neck. A landfill of expired dreams and expired hopes, he was an archive of yet another life wasted by cocaine production and global capitalism.

In all capitalist activity, whether it’s uranium mining in Gabon or sugar planting in Cuba, humans are an input of production meaning that they come out of production different than who they were before. Meeting demand comes at a cost, but in a global economy shaped by inequalities of power, those far from centers of production never have to see the true price of production.

In the case of cocaine, the costs of production are extreme; it is an example of global capitalism at its worst.

Part of this stems from cocaine’s extreme profit margin created by a broader American policy of criminalization. Coca can only grow in the foothills of the Andes. Therefore, the value of cocaine stems not from its ingredients but from the cost it takes to move the drug to the market where it is in demand, in Europe and the United States. A kilo of powdered cocaine in Colombia sells for only $1,700, whereas in New York City, that same kilo sells for $20,000 to $30,000.

Because cocaine remains illegal, and moving it is a risky endeavor, the difference in price factors into that cost. But, if El Mono’s life is any testament, the street price of cocaine, regardless of place or customer, does not factor in the human suffering that makes it consumable.

Of course, this is not to say that cocaine production has to be so violent. After all, Bolivia and Peru, where cocaine was first produced, have never had the same struggles with armed conflict as Colombia. But what cocaine has done, is it has turned Colombia’s historic struggles over land and dignity into a protracted conflict with too many actors and no direction.

As long as Colombian campesinos cannot make a living from their land, they will continue to produce cocaine and different assortments of armed groups will purchase and traffic their mercancía. In turn, armed groups will continue to exploit and kill them–it’s the only way they can keep their share of drug profits in a competitive illicit market. All the while, the Colombian government and its US sponsor will continue to throw up their hands and attribute the deaths to crime. They will rationalize the dead as people who deserved to be thrown away. But it is not solely a Colombian problem.

The drug trade is a global phenomenon. Variations of its injustice appear in many places and in many forms, Mexico and the United States are prime examples. It is an industry that adapts to local circumstances, but it consistently targets the people who are most marginal. Addressing its worst abuses will require collaborative efforts at the global, national, and local levels. A multifaceted approach is necessary to tackle this complex issue.

Paths Forward

From a more global perspective, the United States could adopt a less punitive approach to drug consumption and drug trafficking that recognizes the dignity of all people involved in the supply and demand chain. It would require treating drugs not as substances that are meant to be eradicated, but as substances that are meant to be regulated. 52 years have gone by since President Richard Nixon declared his so-called War on Drugs. Demand and supply for drugs his government made, and continues to make, illicit remains unchanged, and yet, bodies and ruined lives continue to pile up. The costs of drugs, and particularly cocaine, remain too high.

To really put a dent in these numbers, the United States must remove the wider monetary incentives that make the drug trade so lucrative and profitable. One way to do this is by spearheading a global movement to legalize hard drugs, such as cocaine. This would remove the financial pull for armed groups to participate in the drug trade. It would also establish regulated channels for marginalized individuals, like campesinos, to sell drugs to legal entities and in so doing, give them a chance to earn a stable income without fear of violent competition. Governments could then tax the transactions and use the money to spread awareness about the drugs in question and to provide medical services to those who use or become addicted to them.

The US could learn from global leaders in drug policy, like Portugal and Switzerland, for ways to finally combat the drug trade not with weapons, but with empathy. Fighting communities who rely on the drug trade simply creates more rancor and bitterness that pushes people further into the hands of armed groups who although callous, provide them with what the government cannot, a living. Perhaps it is time for governments to provide their people with the dignity and respect they are supposed to. Giving them the esteem of legitimacy is a start.

From a national angle, the Colombian government could implement its long elusive land reform. Providing campesinos with land they could subsist on would prevent many from subsisting on the drug trade. Further, giving them legitimate claims to their land, would disincentivize armed groups from evicting them, as campesinos would have legal course to remain on their property. Bogota could also enact a broader strategy of reparation, through social welfare, that recognizes all poor Colombians as victims of the conflict because the line between victim and victimizer in a country at perennial war is impossible to draw. It is only with a policy of compassion and understanding that Colombia will begin to extinguish its centuries’ long fire.

And yet there are people who have been doing this locally with little recognition or support from the government. While El Mono did not follow their example, he was certainly the beneficiary of the efforts of individuals like his sister, Paola, and his neighbor, Lucero, who looked after him because he could not take care of himself. While he was not moved by their example, there are many people who were. I am certainly one of them.

Half a decade later and thousands of miles away, I still remember with gratitude and tears the hours I spent with both of them as they risked their lives to tell me their community’s stories. It is a cruel irony that one of them passed away without a voice. On April 14, 2021, after a short and violent battle with COVID-19, Lucero passed away from asphyxia in a hospital room in Medellin. She was weeks away from getting her first COVID-19 vaccine. She died alone and out of breath away from her family and the community, the flower in the desert, she had worked so hard to cultivate. It was an unextraordinary end to the life of an extraordinary woman.

Lucero’s death made no headlines. It was caught up in yet another wave of COVID-19 deaths. Like crime, it was framed as a natural occurrence, but it was really another death caused by Colombia’s toxic air. Perhaps if she had been wealthier and not living in an overcrowded home of displaced people, she might have survived. Perhaps if her immune system hadn’t been worn down by sixty years of bloodshed and trauma, she would be here today. And yet, in some ways, she still is.

In the months after she died, I was overwhelmed by the number of tributes Lucero received on social media. I had never seen anything like it. Her kindness and generosity live on in all the individuals, including me, that were lucky enough to have met her. I know there are countless people spreading a helping hand today in her honor. These are the people, those who find the humanity in every person, that our policies should emulate.

If we are to find a path forward, we should look to people like Lucero as guides. Policies, by definition, are works in progress. They must be subject to constant questioning and revisions. But if we view the task of lowering the costs of cocaine as a chance to help the most people possible, regardless of who they are or what they have done, like Lucero did, we may have a chance at breathing new air.

Mariana Calvo is a History PhD Student at Stanford University.

References

None of this work would have been possible without the input and time of dozens of individuals who I had the privilege to interview and get to know. Many of them have passed away since I left Colombia, but it is my deepest hope that their perspectives, words, and dreams live on in this piece. Of the people I can recognize for safety reasons, and who consented to have their names published, I want to express my deepest gratitude to: Paola George, Lucero Usma, Luis Angel Perez, Humberto George, Hugo George, Aicardo George, Luciriam Hernández, Alfonso George, Leonardo Rodríguez, and Lalo Tapias. Gracias por todo. Fueron mis mejores maestros.

Calvo, Mariana. “Colombia’s Land Disputes: What the Life and Death of Hugo George Taught Me,” Colombia Reports, January 12, 2019.

Carpentier, Chloe, Laurent Laniel, Antoine Vella , and Yulia Vorobyeva. Cocaine: A Spectrum of Product. Vienna, Austria: UNODC, 2021.

Cruz, Ricardo L. “Alarmante Deterioro De La Seguridad En El Norte De Antioquia .” Verdad Abierta. Verdad Abierta, January 24, 2018.

Grajales, Jacobo. “Where Have the Criminals Gone?” Politix 123, no. 3 (2018): 171–93.

González, Fernán E. “The Colombian Conflict in Historical Perspective.” Essay. In Alternatives to War: Colombia’s Peace Process. Bogota, Colombia: Centro de Investigación y Educación Popular Por La Paz, 2004.

Hecht, Gabrielle. “Interscalar Vehicles for an African Anthropocene: On Waste, Temporality, and Violence.” Cultural Anthropology 33, no. 1 (2018): 109–41.

Hecht, Gabrielle. Residual Governance: How South Africa Foretells Planetary Futures. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2023.

Human Rights Watch. Rep. Breaking the Grip? Obstacles to Justice for Paramilitary Mafias in Colombia. New York, NY: Human Rights Watch, 2008.

Liboiron, Max. Pollution Is Colonialism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021.

Magaloni, Beatriz, and Alberto Diaz-Cayeros. Violent Crime as a Global Development Challenge: Causes and Menu of Interventions. Stanford, CA, 2017.

McFarland Sánchez-Moreno, Maria. There Are No Dead Here. New York, NY: Bold Type Books, 2018.

Mejia, Daniel. Rep. Plan Colombia: An Analysis of Effectiveness and Cost. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2016

Mills, Charles, and Bill E Lawson. “Black Trash.” Essay. In In Faces of Environmental Racism, edited by Laura Westra, 73–91. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2001.

National Center for Historical Memory. “A Prolonged and Degraded War; Dimensions and Methods of Violence.” Essay. In Basta Ya! Colombia: Memories of War and Dignity, edited by National Center for Historical Memory, 36–116. Bogota, Colombia: National Center for Historical Memory, 2016.

Otis, John. Rep. The FARC and Colombia’s Illegal Drug Trade. Washington, DC: The Wilson Center, 2014.

Oxfam. “‘Divide and Purchase’: How Land Ownership Is Being Concentrated in Colombia.” September 27, 2013.

Smith, Chad L, et al. “Treadmills of Production and Destruction in the Anthropocene: Coca Production and Gold Mining in Colombia and Peru.” Journal of World-Systems Research 26, no. 2 (2020): 232–262.

Steenkamp , Chrissie. “The Legacy of War: Conceptualizing a Culture of Violence to Explain Violence after Peace Accords .” The Round Table 94, no. 379 (April 2005): 253–67.

Turkewitz , Julie, and Genevieve Glatsky. “Colombia’s Truth Commission Is Highly Critical of U.S. Policy.” The New York Times, June 28, 2022.

Verdad Abierta. “Valdivia Vive Bajo Una Permanente Alerta Roja.” Verdad Abierta, February 5, 2019.