African Voices and the Climate Crisis

African narratives are crucial to surviving the fast-approaching climate doomsday that is already a lived reality for postcolonial societies.

Is Africa really reducible to a story of tragedy? Dominant accounts, mostly produced by Western audiences, highlight instability, poverty, and violence. To much of the world, this is “Africa.” As Achille Mbembe has observed, “The continent, a great, soft, fantastic body, is seen as powerless, engaged in rampant self-destruction” (2001:13). While this focus on Africa as a place of violence has endured, this focus is also deceptive. Africans fighting for decolonization were waging a global struggle. They also had to navigate the intrusive interests of Cold War powers. Viewing the continent without considering these contexts has only dehumanized Africans and their varied political aspirations.

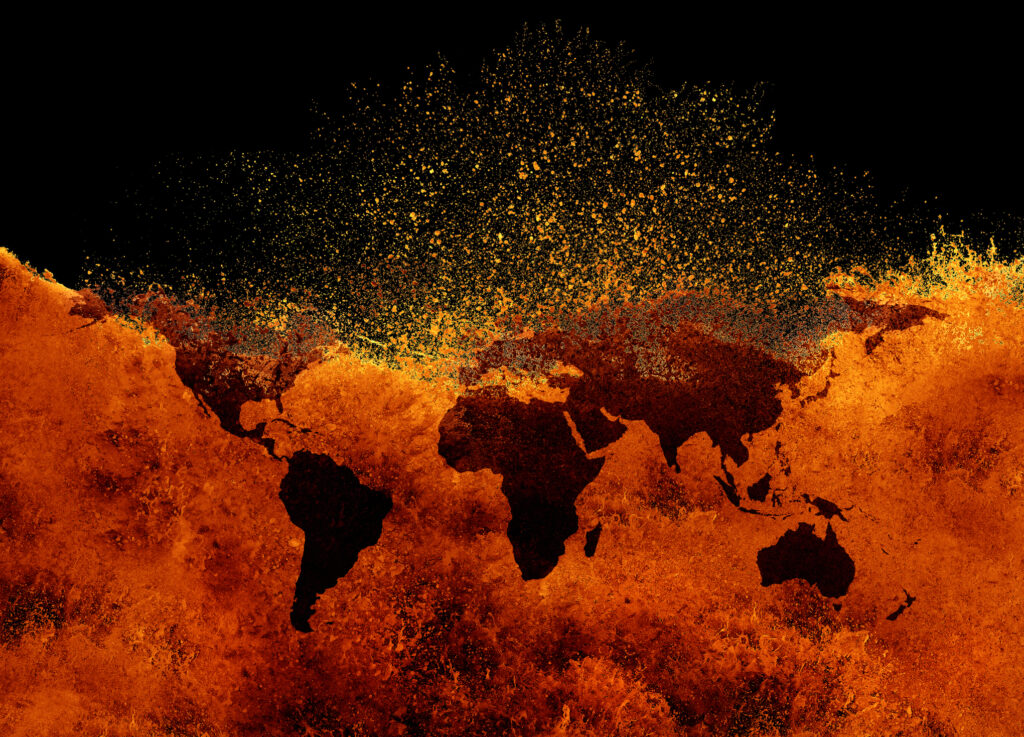

Recent visual representations of Africa have tended to reinforce views that Africa is irredeemable. Desolate images of the environment, near apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic features of radioactive toxins, of pollution and petroleum-related violence in the Niger Delta, of uranium extraction in Arlit in Niger, and diamond mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo all reinforce this perception.

Scenes of devastation and despair flood Western media. They project a narrative that makes commonplace the idea that instability and violence are common features of African societies. Yet, they fail to ask how they might frame a different reality and consider evidence of environmental violence with a very different history.

Extractive Practices

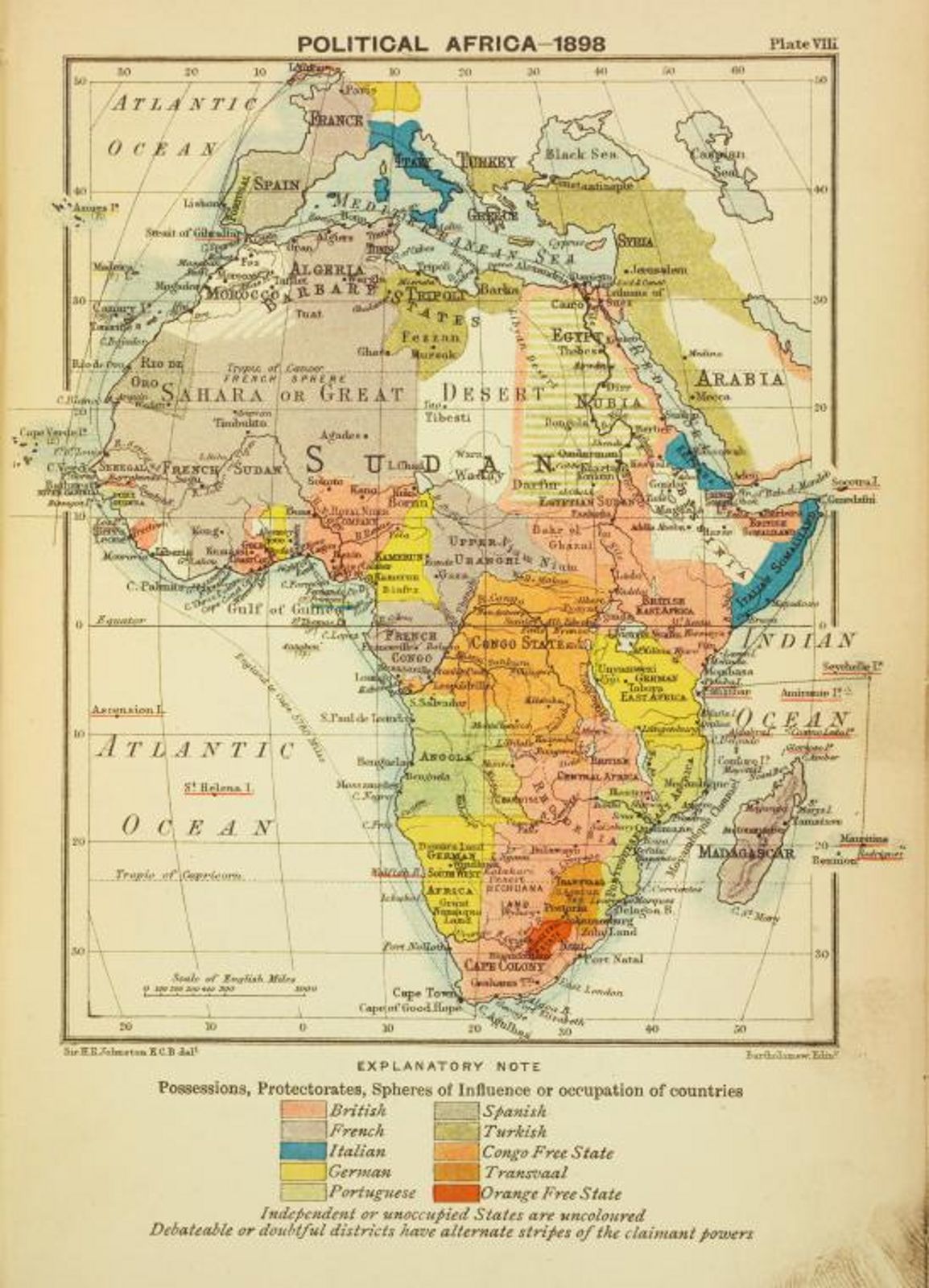

To fully comprehend the ongoing environmental crisis across the African continent, climate change needs to be placed in the broader context of African global histories. We must evaluate the history of European imperialism, beginning with the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 and the “Scramble for Africa” that it helped to unleash. European powers split the African continent into different colonies where they had ultimate ruling power. The main contenders that partook in the new power struggle were the five main European rivals: Germany, Italy, Portugal, Britain, and Spain.

“Political Africa – 1898.” New York Public Library Digital Collections

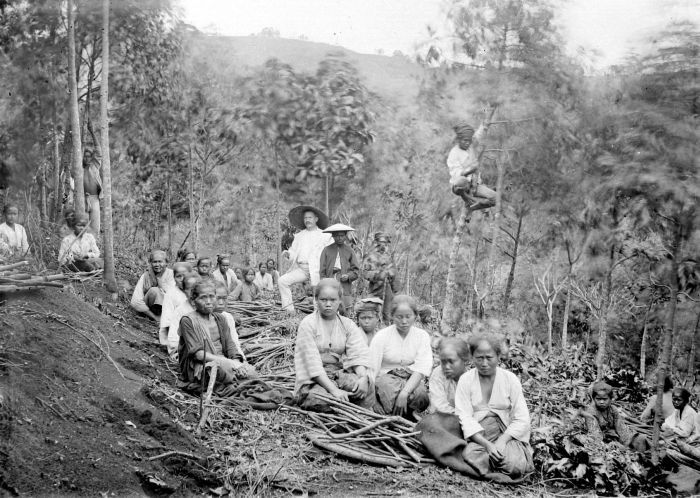

Dissecting and tearing African land piece by piece gave Europeans total control of the entire continent. The Berlin Conference saw Western powers scramble for the extraction of African resources, directly fueling the ecological violence that still shapes current realities on the continent.

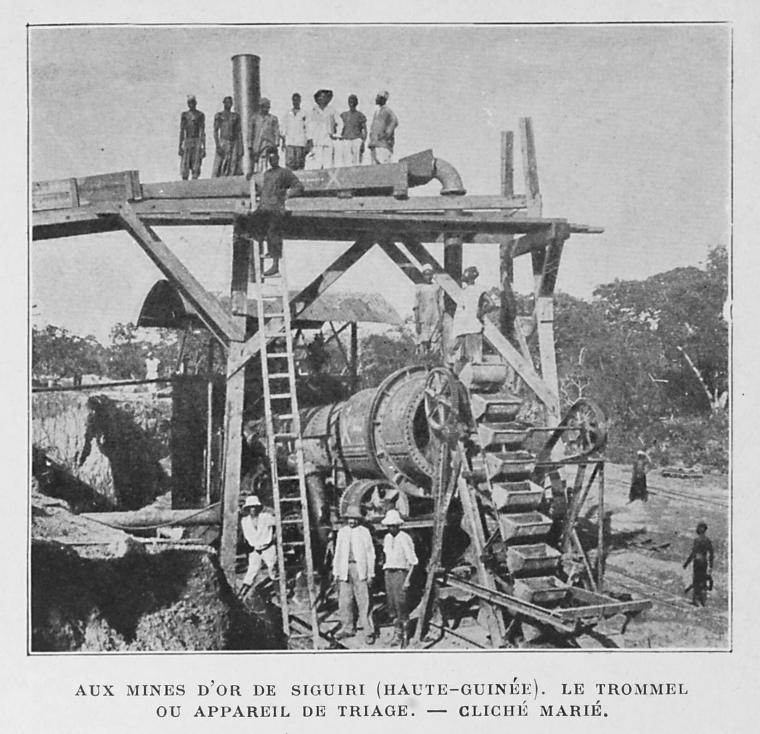

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. “Aux mines d’or de Siguiri (Haute-Guinée). Le trommel ou appareil de triage.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1912.

Fantasy of the not yet future

We all live in the age of the Anthropocene, a time when human beings have altered the Earth’s natural flow by interacting with nature in wats that have destroyed the environment at an alarming rate. In this doomsday era, the environmental scientist Erle Ellis observes, “humans are changing Earth in unprecedented ways” (2018:2). One of the hallmarks of this era is the misplaced assumption that humans cannot share the planet with non-humans (flora, fauna, and animals, to name a few). However, this commonplace notion, so frequently met in Western environmental thought, is contradicted by the history of postcolonial indigenous communities such as the Sengwer indigenous community in Kenya, who have long maintained an intimate relationship with the non-human.

The current Anthropocene narrative is haunted by the presumption that doomsday is looming around the corner. This framing of climate crisis tends to see the West hallucinate around the idea that climate change will never touch them, while those in postcolonial societies are navigating hell on earth as they bear the brunt of planetary change at an alarming rate.

As a challenge to this way of thinking about our climate crisis, African voices are vital to understanding how we might navigate this dreaded future, which is already the lived reality of the “Other”. The current realities of environmental crisis in Africa appear to be near-apocalyptic. Lives are shaped by abandoned homesteads, polluted rivers, gas flares and deforestation in places like Nigeria ( in the Niger Delta), Kenya (Ihithe) and South Africa (Rustenburg). While these all represent daunting environmental challenges, locals are in a unique position to address what it means to live in the shadow of a doomed future. Their lived experiences challenge the generic and flawed descriptions of actual events that downplay local’s engagement with ecological catastrophe. Centring locals’ perspectives here allows them to speak for themselves.

Climate change and Africa

Climate change is a global issue that disproportionally affects African countries in several ways. These are at once morphological economic, socio-political, and physical. Yet the long history of violence and imbalanced exchanges between the West and Africa has compounded the reductive ways the impact of the environmental catastrophe in Africa is understood and represented in the West. This has deepened the communication gap between African ways of being and knowing and Western responses to the body of knowledge emerging from the African continent and the Global South at large. Taking stock of this distortive lens, Byron Caminero-Santangelo has observed that “Western environmental knowledge… suggest[s] that Africans do not understand and abuse their environment and[ that] the Western experts […] need to protect it” (2014:3).

African voices are left out of international conversations when it comes to addressing climate issues on a global scale. “When the world literally burns from climate and political turmoil,” Nnimmo Basse has argued, “it is possible for Africa and other vulnerable regions to be overlooked.” Caminero-Santangelo adds that “mainstream Western environmentalism has often occluded environmental damage in Africa”(2014:2). This narrative imagines the West at the center of the climate crisis. And little to no attention is paid to postcolonial voices, even though climate change is an issue that affects everyone. Brushing aside non-Westernised environmental knowledge has justified overlooking the environmental degradation of the African landscape and the catastrophic effects of environmental issues.

Environmental crisis issues within the African continent are oftentimes described from a generic and generalised lens of Eurocentric romanticization of the African landscape. William Slaymaker touches on this by highlighting how, “[T]he bulk of nature writing about sub Saharan Africa particularly as practiced by white writers is connected with the Euro-American academic literary traditions of thematizing landscape, space, and conservationism and with popular conservationist narratives in books and films” (Olaniyan & Quayson 2007: 683). Through this thematization, the African landscape becomes a celebrated cause in Western consciousness where once again the West assigns itself the role of being the sole gatekeeper to the African natural world.

Planetary consciousness

Ecological crisis in the African continent is misrepresented and brushed aside in a global stage, a tendency rooted in the assumption that bearing the brunt of planetary change is a ‘normal’ aspect of lives adapted to a culture of suffering in postcolonial geographies. As Sonia Tascon has observed, “the face of violations will likely be of people in faraway places and will but reproduce a pre-existent belief that these sorts of things happen over there but could not readily happen here” (2012: 872). The idea persists that the suffering of ethnic and racialised bodies in the ongoing climate crisis is somehow acceptable.

However, the existence of African cultural texts and art challenges this ideology of people in faraway places. Consider Helon Habila’s Oil on Water (2010), Imbolo Mbue’s How Beautiful We Were (2021), Sammy Baloji’s photomontage Memoir (2006), and George Osodi’s photograph Blackened Explosion (2004) to name a few. Their works ask readers and spectators to critically engage with, and understand, how climate change affects everyone irrespective of their geopolitical settings. Their cultural works link environmental racisms and human rights from a local to a global perspective, while simultaneously reinstating the role of the African continent and the Global South as integral voices whose inclusion is essential in discussions of the ongoing climate crisis.

Habila and Osodi’s work capture the lived realities of inhabitants of the Niger Delta region. The two Nigerian creatives use literature and photography to provide a nuanced representation of how locals in the Niger Delta navigate life in a dying landscape. The use of fiction and photograph draw attention to overlooked issues. Instead of treating, environmental violence as just another endemic feature of a culture of suffering in the region, Habila and Osodi show how locals’ proximity to the pollution, gas flares, and degraded landscape places them in a unique position to understand the urgency of finding practical solutions to tackling climate change issues before they reach a place of no return. Thus, it becomes crucial that we turn to missing postcolonial narratives to see how the rest of the world can learn about solutions worked out in the Global South.

There is a re-emergence of planetary consciousness about environmental problems that are decimating the African landscape and curtailing African’s chances of accessing a future. Rob Nixon’s book Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (2011) shows how homogenous, Western, and Eurocentric approaches dominate the environmental literature canon. In building an alternative to this perspective, African writers are now pushing back against being overlooked and bearing witness to environmental degradation affecting their land. New scholarship from the last few years like Jennifer Wenzel’s The Disposition of Nature: Environmental Crisis and World Literature (2019), Byron Caminero-Santangelo’s Different Shades of Green: African Literature, Environmental Justice, and Political Ecology (2014), Cajetan Iheka’s Naturalizing Africa: Ecological Violence, Agency, and Postcolonial Resistance in African Literature (2017), Iheka’s African Ecomedia: Networks forms, Planetary Politics (2021) and Achille Achille Mbembe’s Out of Dark Night: Essays on Decolonization (2021), to name a few, all touch on the issue of the Anthropocene from uniquely African perspectives.

Mobilizing the missing African voices

Through their rich dialogues and refreshing approach to the climate crisis, African cultural texts introduce a global audience to African epistemologies and indigenous and local knowledge production. Africanists like Achille Mbembe and Cajetan Iheka re-center Africans’ role on the global stage as they produce new thinking to act as a counter-narrative to the dominant Western ecocritical perspective. As Iheka observes, “[T]he growing number of cultural artifacts textual, pictorial, aural, and other devoted to African environments is, a recognition of the climate crisis and the increasing risks to our ‘animate planet’” (2021:17).

African artists and writers are producing works through various media to highlight African individuals’ lived realities. The different modes of artistic expression call for looking at how African cultural text offers new solutions and approaches to the future. African filmmakers like Wanuri Kahiu’s Pumzi (2009), Frank Bieleu’s The Big Banana (2011) and Catherine Meyburgh and Richard Pakleppa’s Dying for Gold: The Untold Story of the Making of South Africa (2018) investigate the misrepresented and downplayed ecological issues across the continent. The filmmakers offer nuanced perspectives exploring how doomed future feared in the West is already a lived reality for postcolonial subjects.

Africans have mobilized themselves in the struggle against climate catastrophe by adapting different survival modes that push beyond a Western paradigm. They are documenting ecological effects and centering micro-minorities and disrupting Eurocentric perspectives. An example is visible in Kenya with the establishment of the Green Belt Movement, founded in 1977 by Wangari Maathai. It emerged as an environmental response to several environmental issues that impacted rural Kenyan women. Maathai challenged environmental insecurity and, shortages of food, and water. Rural women in Kenya actively participated in the Green Belt Movement and were able to identify environmental issues and come up with practical solutions such as planting trees. The movement also looked at how women had to walk long distances to access firewood because of the deforestation in the area. Maathai’s movement showed Kenyan’s potential to address the unfolding climate crisis in Kenya at the time. Crucially, the movement showed Kenyans’ ability to come up with solutions without relying on external agents like wanting to be saved by the West.

African writers, scholars, filmmakers, and artists in regions like Kenya, Niger, and elsewhere are working to situate the African subject in conversation with the temporal framework of the future. Their current reality involves near apocalyptic scenarios shaped by pollution, deforestation, and toxins, among other threats (Wenzel 2020:84-89). Their arresting narratives provide spectators with a scenario that unmasks an unimaginable future. The visible presence of African voices in speaking out and raising awareness about the alarmingly fast rate of climate change and its extensive effects shows the urgency of the situation. As the Ugandan activist Vanessa Nakate explained in an interview with Angelina Jolie for Times magazine. “People need to understand that the African people have solutions that will change the world.” Her interview serves as an important affirmation of the role African narratives must play in developing coping mechanisms and survival strategies for the future of the planet.

What now?

African ways of being and knowing, through cultural texts, are offering fresh ideas that center voices from the Global South, which can no longer be ignored. Pre-existing knowledge about the natural environment and the long-lasting history of violence and trauma offer nuanced ways of creating coping mechanisms to approach the future in the era of the Anthropocene. Attention to indigenous knowledge promises new thinking that disrupts and challenges dominant Western ecocriticism.

In my experience, conducting my PhD research on climate change from a distinctively African perspective has helped me understand the intersecting global histories of environmental injustices, human rights, environmental racisms, and the tensions of representation that exist between the colonial dualism of the West and its ‘victims’ (Africans). Climate change affects everyone, so it is essential to consider African and other global perspectives in identifying solutions and coping mechanisms. The nature of our climate crisis demands modes of thinking drawing on all forms of knowledge, including those articulated by the missing postcolonial voices. To have a fighting chance to produce meaningful alternatives to the status quo and come to terms with the unfolding climate catastrophe, we must all act now.

Sandrine Uwase Ndahiro is completing her PhD studies at the School of English, Irish and Communication at the University of Limerick.

References

Caminero-Santangelo, Bryon. Different Shades of Green: African Literature, Environmental Justice, and Political Ecology. Charlottesville; London: University of Virginia Press, 2014.

Iheka, Cajetan. African Ecomedia: Network Forms, Planetary politics. New York: Duke University Press, 2021.

Mbembe, Achille. On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Mbembe, Achille. Out of the Dark Night. New York: Columbia University Press, 2021.

Nixon, Rob. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Olaniyan, Tejumola & Quayson, Ato. African Literature: An Anthology of Criticism and Theory. Oxford: Blackwell, 2007.

Tascon, Sonia. “ Considering Human Rights, Representation, and Ethics: Whose Face,” Human Rights Quarterly, vol.34, no.3, 2012, pp. 864-883.

Wenzel, Jennifer. The Disposition of Nature Environmental Crisis and World Literature. New York: Fordham University Press, 2020.