After Anthropology

How plant geographies might reveal racialized pasts and help forge protean futures.

THIS ESSAY IS PART OF THE SPECIAL ISSUE “AFTER LIFE: IDENTITY AND INDIFFERENCE IN THE TIME OF PLANETARY PERIL.” IT FEATURES PAPERS PRESENTED AT THE INAUGURAL SYMPOSIUM OF THE DEMOCRACY INSTITUTE AT THE AHIMSA CENTER AT CAL POLY POMONA, WHICH WAS CO-SPONSORED BY THE INSTITUTE FOR NEW GLOBAL POLITICS, IN MARCH 2023.

Prologue: Proteacea

“The genus Protea was named in 1735 by Carolus Linnaeus after the Greek god Proteus, who could change his form at will, because proteas have such different forms. Linnaeus’s genus was formed by merging a number of genera previously published by Herman Boerhaave, although precisely which of Boerhaave’s genera were included in Linnaeus’s Protea varied with each of Linnaeus’s publications … Proteas attracted the attention of botanists visiting the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th century. Many species were introduced to Europe in the 18th century, enjoying a unique popularity at the time amongst botanists … The extraordinary richness and diversity of species characteristic of the Cape Flora is thought to be caused in part by the diverse landscape where populations can become isolated from each other and in time develop into separate species.”

No Ka Oi Protea (A plant business selling Protea bouquets in Hawai’i)

(Un)Natural Histories

The California super-bloom of 2023 had been trending on Instagram. Flowers were back with a vengeance after years of drought, fire, and heatwaves. In the early spring of 2023, I was part of a small group of scholars visiting the Cal Poly Pomona campus; we spontaneously exclaimed in awe as we came across a protea plant in full spring bloom.

We had spent two days in a closed auditorium speaking about the hidden scripts of democracy and the forms in which oppressed peoples dream about the future, but we hadn’t talked about how much history was held in the landscape around us. The land we were on was called Torojoatngna when it was the native lands of the Gabrielino-Tongva, Serrano and other Takic-speaking people. The Protea plant, like the diverse group of scholars admiring it, was non-native; it had arrived in these southern California hills from elsewhere. The plant was probably cultivated by a local breeding business and nurtured by campus gardeners, but before that, it had arrived here via eighteenth and nineteenth-century networks of colonial trade and plant geographies. Both at its origin and at its destination, there were histories of displacement of Indigenous people.

Cal Poly Pomona gardeners’ expert hands reminded me how much history our landscapes hold. The protea is one of the most diverse and ancient of plant genera, its history linked with the physical geography of Gondwanaland. Looking at the plant in the first outpouring of spring vigour brought my thoughts to the ways in which plants travelled in the wake of the eighteenth-century explosions in European taxonomy. I recalled an independent-film classic from twenty years ago, Proteus, made by South African filmmaker Jack Lewis and Canadian filmmaker John Greyson, set in eighteenth-century South Africa. To explore the connection between a protea blooming in southern California and a queer film named after the same plant, I find myself meandering through seemingly disparate realms: the history of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century botany and twenty first-century queer cinema.

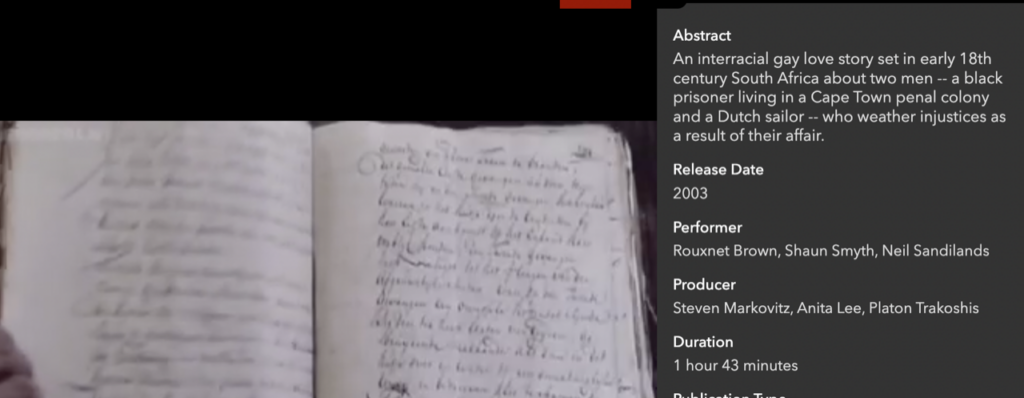

Proteus is described on IMDB as “an interracial gay love story set in early 18th century South Africa.” South African film maker Jack Lewis, while reading in the South African archives, came across an account of an interracial same-sex couple who were put to death in 1735. The 2003 film he made with John Greyson, based on these archival fragments, was named Proteus; the love story between the central characters, Claas Blank and Rijkhaart Jacobsz, is intercut with images of the protea flower blooming, and dying. Among the characters framing the film’s central couple is Virgil Niven, a Scottish Botanist who befriends and seduces Claas, an Indigenous Khoi prisoner on Robben Island, seeking his expertise in local plant identification.

Indirectly, eighteenth-century taxonomist Linnaeus and his sexual classification system are structuring metaphors for the film. The King Protea is the national flower of South Africa. Most of us know that plant geographies and Indigenous histories are connected, but these connections occupy troubled zones in the histories we extract from colonial archives. Proteus became a gay film-circuit favourite, but its historiographic allusions remained opaque to most audiences. Where audiences expected a love story that transcended time and place, the filmmakers gave them forms of never-innocent intersubjectivity, imbricated with historical context and political imagination.

The pages we see as the film begins are an actual archival record of the prosecution of Claas Blank and Rijkhaart Jacobsz for their “unnatural” relationship. The prisoners — one deported from Rotterdam as a teenager, the other torn from his Indigenous Khoisan community — had been in a relationship for over a decade before a political confluence of global events, including period of homophobic moral panic in Amsterdam, named and incriminated their practices. It was the discovery of this archival trace that started Jack Lewis and John Greyson on the project.

The filmmakers themselves have discussed all the threads that made this a historiographic exploration, but the density of this historical story (well-known to historians of botany, but arcane to others) makes it obscure for film critics and fans alike. For example, Jack Lewis has called inadequate “the narrow classification of Proteus as a “gay” movie in a niche market.” The film received lukewarm reception by mainstream film critics (for example, a NY Times review called it “pretentious”) because its historiographic references seemed opaque.

However, a viewer attuned to the history of botany notices immediately the way that plant geographies in general, and Linnaeus in particular, frame the film’s narrative. While Claas Blank and Rijkhaart Jacobsz are the real names of the historical figures who were put to death by a colonial state in the midst of a sexual panic, the botanist figure, Virgil Niven, is constructed out of a mélange of global botanical explorers who used colonial networks to test and expand Linnaeus’ sexual taxonomy.

Sexual classification is a way of framing the central aporias: queer love that has no name, and Indigenous knowledge that has no status. Plant geography and the politics of historiography all entangled in this film, which is as much an essay on historiography as it is a love story. The film makers deploy anachronistic jump cuts, linking histories of the eighteenth century to twentieth century histories of place, knowing that Robben island would be more well known to their audiences as the incarceration site of Nelson Mandela. This entangled complexity is key, I think, to the incomprehension with which mainstream critics reviewed it. For example, reviewer Kevin Thomas, in his review of Proteus for the LA Times, found the anachronism incomprehensible, while he extracted the flower metaphor into a universal symbol of love, rather than following the historically-embedded critique of European taxonomies.

“[The] constant sprinkling of anachronistic dress and objects throughout the film is merely a distraction … Much more effective is the filmmakers’ concern for the mythology of Claas’ people and the use of South Africa’s exquisite national flower, the king protea, as a symbol of the lovers’ developing relationship.”

Linnaeus, whose taxonomy of sexual differences transformed eighteenth-century classification, is the well-known historiographic hinge for the connections between the histories of botany and sexuality. Linnaeus was not the first scientist to taxonomize, but he was the first to establish sexual classification as the primary taxonomizing logic for understanding the human and natural world.

Jack Lewis explicitly connected Linnean classification of the “Hottent*t” with the emergence of scientific racism in the eighteenth century: “Carl Linnaeus was not only the father of modern botany, he was also one of the fathers of ‘scientific racism.’” Lewis recounts how Linnaeus’s “famous work of botanical classification included the classification of people into different races each with their own racially determined characteristics,” a connection familiar to historians of botany but little understood by the public. In interviews and writings, Lewis and Greyson are explicit about how closely they researched the connections between empire, sexuality, botany, and race, and how they transformed specific historical contexts into aesthetic and narrative tropes.

In 1735, Linnaeus named the genus Proteaceae. In 1735, interracial lovers Claas Blank and Rijkhaart Jacobsz were found guilty of an unnatural relationship, tied together and drowned in the sea off Robben island. Proteaceae was named and defined by a range of botanists over more than a century, and that history is distilled into the figure of Virgil Niven, whose ability to move with the power of military and administrative networks, to extract local knowledge from Indigenous contexts and transfer it to the metropole where he could establish naming and ownership rights, and to sexually exploit his botanical “assistants” encapsulates a story whose complexity historians have only recently begun to grasp. The fictionalized Virgil Niven names a plant protea blanka (described as beautiful and blooming only at night); he accompanies its description with a stereotypically primitivist image of Claas Blank.

Linnaeus’ binomial sexual classification provides the filmmakers with a generative metaphor. Their critical analysis of heteronormative colonial rule is narrated through an expressive metaphorical language of science and Indigeneity that, because of its explicitly political, presentist, and anachronistic tropes, remains outside the bounds of mainstream historical writing.

The filmmakers say: “The liberties we took in making [the Linnaean botanist’s] cultivation of that flower family take place on Robben Island at the same time as the decadelong relationship of our prisoners allowed us to mobilize the metaphors of binomial classification, and in a broader sense the central question of naming that drove our story: what names could Claas and Rijkhaart have for each other, for their feelings, for the sex they shared?” The naming and criminalization of their queer love were co-eval, and interdependent events. Bodies and plants, love and community, could never be the same again.

Individuals, human and plant, could not be narrated or understood through the same names and narratives as they could a quarter century before. This is not to render pre-Enlightenment relationships innocent, but to emphasize that something new was happening in this moment, and it centered on naming tropical nature and packaging people into emerging natural categories. The transporting and cultivation of plants had been practiced for millennia, but something about this moment of naming and classification, emerging along with a trans-oceanic network of infrastructure and an expanding imperial political economy of plant-based commodities, enabled disparate practices of plant collection to congeal into a globe-spanning network of power.

Below, a few vignettes from the film’s opening offer an opportunity to revisit some key moments in plant geography and its ethical, political, historiographic challenges.

In one of the opening scenes, Claas, the Khoi character, fleeing from racist allegations of being a “Hottent*t thief,” hides in a box of plant specimens. As they capture him and prepare to torture him, the Europeans express concerns for the safety of the plants, and for the danger of their bruising from his fugitive body. The value-distinction between Claas’ raced body and the plant specimens is performed on screen even as the main narrative is about forbidden love.

There is a potent pluralism in the screen narratives we watch; to extract a simple love story from it (as critics attempted to do) is to ignore the historical struggle to contest and be free of this anthropological moment: the moment in which the native, and nature, are reframed, for modern consumption. The audience watches, in the violent capture of Claas and the careful boxing of plant specimens, a performance of the differing valuations of Black bodies and green plants.

One kind of connection between humans and nature is being severed in order for another to be produced. Tropical nature — ripped from its living context and “saved” as specimens in a box to be transported to European metropoles — after this moment is set up to be rescued from tropical natives, themselves ripped out of living societies, cast into an anthropologized, fugitive, isolation, enforced by scripts of criminality.

The film’s fictional European botanist, Virgil Niven, who tracks and surveils the central couple throughout, functions as a voyeuristic metaphor for eighteenth-century botanical knowledge production as well as early modern legal moralisms and panics around sexuality. He extracts plant knowledge–and sexual favours–from Claas; this form of knowledge extraction is normalized as scientific discovery. He spies on Claas and Jacobsz; he watches their trial and their deaths at the hands of a colonial state; he has male lovers who are in unequal power relations with him, yet he returns to his heterosexual marriage, home, children, and botanical specimens in Amsterdam, remaining unscathed by the sex panic. His life and his plant specimens remain seemingly untouched by the violence surrounding the extraction of knowledge from its historical environs in Southern Africa.

The role of Indigenous knowledge in the construction of European botany, and the violent expropriation of local knowledge via the casting of Indigenous bodies as equivalent to the bodies of plants and animals, couldn’t be more clearly laid out in the film’s images.

But what was so special about this historical moment of classification?

Linnaean sexual taxonomies

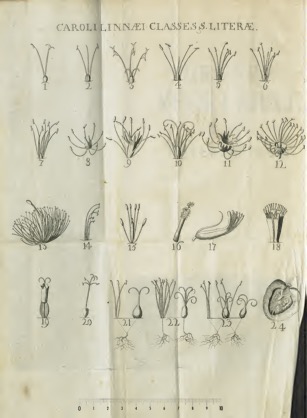

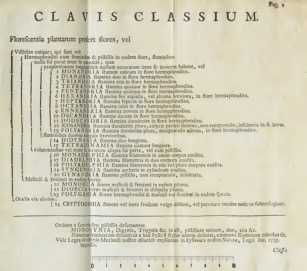

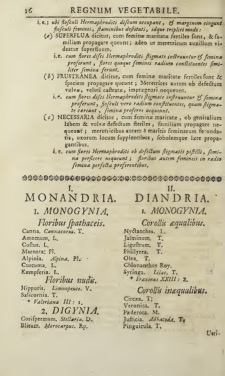

In 1735, Carl Linnaeus published the first volume of Systema Naturae, his classification of the plant, animal, and mineral kingdoms. His use of binomial nomenclature and sexual classification, combined with an explosion in plant collection and classification in the eighteenth century, would cement his reputation as the father of modern taxonomy. The images below (in the Latin original and English translation, taken from the 1737 edition in which he supplemented his text with the illustrations of Georg Dionysius Ehret) show some of the ways in which metaphors of sexuality supplied the structuring system and interpretive meanings for the plant world.

Linnaeus extended his observations of plants (through a dynamic archive continually expanded by global travellers who accompanied the voyages of exploration of the eighteenth century) to all living things. By 1758, the 10th edition of De Systema Naturae, through its taxonomic structures (elaborated via international plant specimens whose collection and transportation were enabled by colonial ships and administrations), laid the foundation for many of the forms of scientific racism that would be deployed in the field of Anthropology for the next two hundred years. “Whereas the previous editions classified man within four lines, the 10th edition devotes 5 pages to the genus Homo,” notes the Linnean Society.

In September 2020, The Linnean Society of London, attempting to “confront the consequences of scientific racism,” acknowledges that in this tenth edition, building on a profusion of classificatory schemas that grew contemporaneously with slavery, colonialism, and voyages of scientific discovery, Linnaeus outlined a set of hierarchical classifications for all of humanity and nature, sedimenting “an idea which became fundamental in the history of Anthropology and has had devastating and far-reaching consequences for humanity, including the dehumanisation of non-Europeans and justification of evils like slavery and indigenous genocide.”

“In the ‘monstruous’ variety, Linnaeus also placed the Hottentots who according to him were less fertile, owing to the fact that they had only one testicle (hence the name Monorchides), and European girls with artificially constricted waists (‘Juncae puellae abdomine attenuato’).”

Other works of Linnaeus show the influence of eighteenth century thought on the development of his racial schema: Critica botanica (1737) and ‘Anthropomorpha’.

Although anthropomorphic, heteronormative metaphors of marriage are everywhere in Linnaeus’ taxonomy, he also seemed to enjoy the discovery that plant sexuality was far more varied than human sexuality was believed to be at the time. For example, only one class of plants in his taxonomy was listed as monogamous, as a result of which his taxonomy described as licentious and shocking by many of his contemporaries.

The taxonomic system enabled plant collectors to classify any plant in the world according to the construction of its reproductive structures. Thus Linnaeus spent pages describing the number and arrangements of male parts (stamens) and female parts (pistils). So for example, the class Monadelphia could be described by stamens in which “Husbands, like brothers, arise from one base,” while he described the class Polydelphia with a diagram showing that “Husbands arise from more than two mothers.” In Monoecia, “Husbands live with their wives in the same house, but have different beds;” in Dioecia, “Husbands and wives have different houses;” and Cryptogamia is characterized by “Clandestine Marriages,” in which “Nuptials are celebrated privately.” The process of classification required botanists to describe detailed topologies of plant sexuality.

Linnaeus’s critics and competitors came up with alternative descriptions of his plants, attempting to expunge sexual metaphors and substitute military, church, familial, tribal, and other social organizational metaphors. Others, like Erasmus Darwin, embraced and exaggerated the provocative sexual metaphors and extended Linnaeus’s scientific insight into a new genre of botanical verse (see The Botanic Garden, 1789, by Erasmus Darwin, whose preface mocked military metaphors). Historian Samantha George refers to this scientific play of metaphors as illustrating “the dialectical ambivalence of Linnaean botany as applied to society,” showing competing ideals of hierarchy, anarchy, and emancipated sexuality.

I emphasize this play of metaphorical and botanical connotations to note that the politics of imperial classification did not follow in any linear way from Linnaeus’ choice of sexual metaphors. Metaphors could not function alone; they needed politics, economy, infrastructures, and armies in order to bring changes into the world. In that process science did not emerge as a set of universal ideas from above — scientific knowledge itself materialized, ground up, via the practices of imperial world-building.

It is impossible to understand the historical emergence of science without speaking of the violence that enabled this kind of knowledge production. But it is also too simplistic to read gendered and racialized politics directly from metaphors, without situating the power of those metaphors in their political and economic contexts.

The eighteenth century saw the growth of high-profile plant-collecting expeditions sponsored by every European state that had global ambitions. The continent of Africa was central to the expropriation of land and labour under multiple imperial regimes. The South African Cape region’s biodiversity attracted a scramble for taxonomic data in the wake of Linnaeus’ publication of Systema Naturae.

Every empire had plant collectors who spread around the world and established gardens as hubs for what later came to be called economic botany. For the British empire, Kew Gardens (originally a recreational space for Princess Augusta, the mother of George III) became the plant hub of the imperial world. In 1768, English naturalist Joseph Banks accompanied Captain Cook to the South Pacific, sending back seeds to Kew. On his return, he became Kew’s first (unofficial) director. In 1772 Francis Masson, Kew’s first official plant collector, went on a collection voyage to South Africa and returned with thousands of plants.

Plant hunting was not purely a European imperial obsession. In the late eighteenth century, everyone was seeking plants. For example, South Asian monarch Tipu Sultan demanded of Louis XVI (who sought a subcontinental ally against the British) that the French fulfill “the requirement of friendship” with Mysore by sending various gifts: arms, crafts, artisans, and critically, a collection of plants accompanied by a team of gardeners to keep them thriving.1

In 1792, a Buddhist monk in inner Mongolia named Jam Dpal Rdo Rje produced a manuscript that studied plants alongside medicine and zoology. According to historian Carla Nappi, Jam was writing a form of materia medica that was not derived from the European tradition.2 The study of plants was not necessarily or intrinsically tied to the domination of nature. Multiple scientific epistemologies still thrived in the early modern period. But the stage was being set for some kinds of scientific knowledge to remain in the cloistered zones of curiosity and for others to become powerful in ways previously only achieved by religion and militaries.In the mid-nineteenth century, the “high imperial” phase of empire brought changes in the institutions and organization of plant collection. In 1840 the management of Kew was transferred from the Crown to the British government and the gardens opened to the public rather than remaining a royal pleasure ground. Its director Joseph Hooker moved plants from the Falklands to Kew in glazed “Wardian cases” – these were ingenious portable greenhouses that offered a new kind of infrastructure to keep plants alive on voyages. In 1848 the Palm House at Kew housed transplanted equatorial vegetation in a constructed London-based tropical ecosystem. The technologies of empire were beginning to make the material of the tropics a portable, commodifiable asset.

Joseph Dalton Hooker succeeded his father Joseph Hooker as director of Kew in 1865, becoming one of the most important botanists of the nineteenth century. Being an eminent scientist was inextricable from being connected to the infrastructures and networks of Empire. When we ask what is good science, or what is a great scientist in this era, we should also ask: how did these abstract notions and ideal personas emerge out of the material structures and networks of empire? How was their knowledge enabled by, and coterminous with, the power of arms, networks, infrastructures, and the ingenious technological reproduction of nature far from its contexts?

As tropical nature was increasingly foregrounded as components of European science, tropical bodies experienced a double shift. As nature became scientific object, natives who knew nature were studied as objects of anthropology and denied the subjectivity of knowers. Indigenous knowledges were extracted, while the bodies and contexts of those knowledges were rendered silent and marginal to the global flow of knowledge.

Gin and Tonic

The edible commodities of the nineteenth century—tea, coffee, and cocoa—tell stories of Indigenous knowledge that have largely been forgotten or footnoted in history. There is another plant whose history illustrates this period: the species Cinchona, native to the Andes. While few of us today regularly consume the bark of the cinchona tree (if you have enjoyed a traditional gin and tonic, it’s possible that you have consumed Jesuit’s bark), for much of the nineteenth century this was the most valuable economic plant of all. As the Madras Government Museum’s Superintendent wrote to Kew Gardens in 1879 in effusive praise of cinchona: “it is not too much to say that if portions of [England’s] tropical empire are upheld by the bayonet, the arm that wields the weapon would be nerveless but for Cinchona bark and its active principles.”3

Image Credits: Ossewa “Fitch & Leedes Indian Tonic” Wikimedia Commons

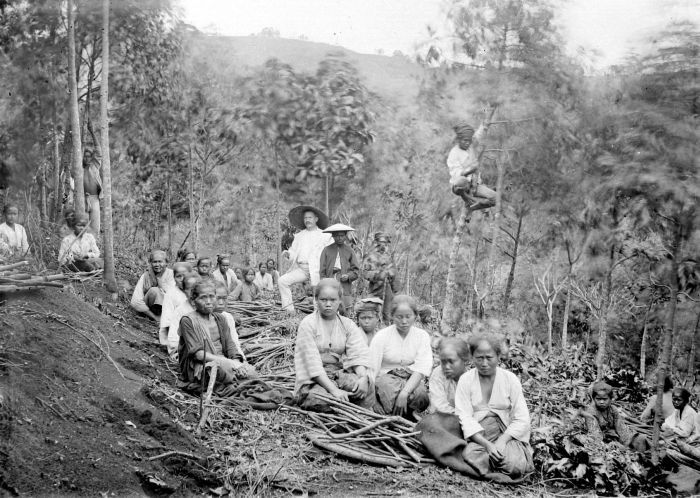

In the middle of the nineteenth century, the British and Dutch were openly competing over the control of the tree, cinchona, that yielded the alkaloid, quinine, that cured malaria. Searching for a home in which to cultivate this healing bark, the British colonial state invited geographer Clements Markham to help them naturalize cinchona in India, and the Dutch commissioned plant hunter Justus Karl Hasskarl to bring cinchona to Java. But neither India nor Java had native cinchona: that had to be stolen from another imperial theatre.

The two explorers engaged in what today would be called “Bio piracy” or the open theft of intellectual property. Although they were in competition with each other, there was also collaboration among other scientists: for example, in1861 the director of Calcutta Botanic Garden Thomas Anderson went to Java and brought back seven cases of plants. Clements Markham learned how to package plants in Wardian cases from Robert Fortune, who was moving tea out of China. In 1862 British scientists proudly sent specimens of Cinchona succirubra, which was by then growing vigorously in India, to provide evidence of their success in locating a hardy, transplantable variety. The continual transfer of seeds and scientific knowledge could happen among competing empires because of the multi-valence of universalized scientific knowledge.

The Dutch succeeded in naturalizing the cinchona tree in Java because British farmer Charles Ledger, working from Peru, ‘discovered’ the productive Cinchona Ledgeriana in its native Andean habitat. The naming of this empire-shaping tree after its white pirate Charles Ledger obscures the history of his Inca guide and teacher, Manuel Mamani. Mamani knew the Andean forests and the varieties intimately, and obtained the specimens for Ledger (who had no idea what to collect).

Charles Ledger might not have had local forest knowledge but what he had was imperial networks: he sent these seeds to his brother George in London, who shopped them around among imperial plant collectors. The British rejected them; they were not interested in buying seeds on this market because they thought their collector Markham’s team had stolen them independently (however, Markham stole a weak variety, Succiruba, that struggled to produce as much as Ledgeriana). When the Dutch finally discovered that the seed variety Ledger carried would grow vigorously in Java, Charles Ledger asked Mamani to get more seeds. By now, after the open British theft of the tree, exporting chinchona seeds and saplings had been outlawed in Bolivia.

Manuel Mamani, forced to hunt for more specimens by his employer Charles Ledger, was captured in the forest collecting the very specimen that he had helped “discover.” He was jailed, was beaten, and died from his injuries. But Mamani’s seeds sprouted in Java and made the Dutch the world’s most powerful traders in the valuable malaria-preventing plant compound, quinine. The death of an Indigenous healer and the alchemy of commodification were co-eval, and contingent events.

Markham, too, was guided in his quest for cinchona saplings by Indigenous Quechua-speaking Andeans. In the Andean Caravaya forests in 1852, he made the acquaintance of cascarilleros (veterans of the South American cinchona bark trade) and collahuayas, collectors of drugs and incense (traditional travelling healers who passed their knowledge of herbs from father to son). Markham employed Mariano Martinez, a cascarillero who had guided the Anglo-French physician Hugh Algernon Weddell on his 1846 visit. He contracted with him to lead him into the forest ‘where no European had been before.’

In his memoirs, Markham describes a long and arduous journey in search of cinchona trees, where he scrambles up ‘giddy precipices,’ entreats and threatens ‘mutinous Indians’, dodges wild animals, injury and disease, and chews coca to dull his hunger. He managed to collect about five hundred cinchona plants of different varieties, which his gardener packed in Wardian cases, specially designed to withstand the long journey to London. On emerging from the forest, however, just as they finished packing the plants, Markham’s local assistant, Gironda, received ‘an ominous letter’, ordering him to arrest Markham and his guide (Martinez), and to prevent Markham from taking away any cinchona plants. Markham recalls that he “felt the imperative necessity of immediate flight, especially as I obtained information from an Indian that [Peruvian military agents] … were coming down the valley to seize me, and destroy my collection of chinchona-plants.”4

I offer these details from explorer’s memoirs to show that in fact the role of Indigenous people in the knowledge networks of the nineteenth century was no secret. Why then was their knowledge not credited by the Royal Society when it was time to name the plants?

It is not that Indigenous people were invisible in the actual collecting and learning that began the process – it was that they could not count as knowers, in the new forms of accounting that characterized scientific knowledge. In a massive global transplantation scheme entered at Kew Gardens, Indigenous Andean knowledge was extracted without recompense, and the trees indigenous to the Andean region were re-settled in Dutch Indonesia and British South Asia. The bark of the tree yielded plentiful supplies of quinine that kept troops free from malaria, but the humanitarian narrative that emerged in imperial discourse rendered its Indigenous origins invisible.

The deaths of Indigenous Andean guides and teachers were not simple accidents. This sort of invisibility, theft, and disposability, were inherent in the structure of modernity’s legerdemain. The birth of plant commodities required the composting of Indigenous culture and knowledge. The commodification of an Andean bark into a global commodity, quinine, enabled the militarization of colonial theatres, as it successfully stemmed the massive number of deaths from malaria in imperial tropical expeditions.

With the rise of Indigenous peoples’ rights to Intellectual property in the late twentieth century, and the global movement to address the racial violence at the heart of modern systems, most scientific institutions, from Kew Gardens to the Linnean Society, have issued statements regretting their role in colonial systems. (The statements on race quoted above, from the Linnean Society, were issued, not coincidentally, I believe, at the time of protest and global reckoning soon after the 2020 killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police.)

The expression of regret at past inequities, however, takes shape as liberal guilt that seeks to put the past behind us, even as the present takes its shape from the past. After 1945, as colonial anthropology took on a bad odour, the study of genetic variation in plants took its place in the new sciences of genetics and molecular biology. Increasingly from the 1950s onward, Kew Gardens put its scientific resources towards building massive libraries of plant genetic material. The role of these genetic resources in the patenting of pharmaceuticals and the making of new forms of property as the century ended is a story with echoes of the eighteenth century.

As the twenty-first century sets it sights on climate mitigation, and COP conferences call for pledges to conservation, Kew has taken a central role in conservation efforts. But critical scholarship has pointed out that threats to locals who live near forests and “biodiversity conservation” hotspots experience displacement, homelessness and starvation as a result of global conservation. Aby Sene, writing in Foreign Policy, has cautioned that the move to militarized conservation of land has already inaugurated a “second scramble for Africa and a “colossal land grab as big as Europe’s colonial era” that will “bring as much suffering and death.”

How is it that in the midst of pronouncements about both concern for the planet and respect for Indigenous people, plant geographies are producing militarization and expropriation once more? Both metaphorically and materially, imperial scientific schemas were seen as bringing order and refinement to alien and inhospitable lands. Quite literally, they aimed to convert “savage” jungles into “ordered” forests.

In material terms, new plant spaces such as botanic gardens created spaces into which only certain types of modern subjects could legitimately enter: the civilized, genteel, sophisticate with the capacity to contemplate nature in its pristine purity. But that pristine purity was produced by severing plants from their histories and socialities. The timeless construction of ‘nature’ that we see in gardens and botanical manuals is available only to the highly educated – or nature for the ‘cultured’ (that is, to truly appreciate nature in all its purity, one had first to possess the requisite cultural training, or scientific sophistication). This reification of a pure or elevated nature, along with its partner, an elevated cultural sophistication, was accomplished through the othering of a corresponding nature-culture pair, namely low or debased nature and low or ‘primitive’ culture.

One of the reasons Indigenous worldviews occupied this position (defined by low nature/ low culture) was because they were represented as having ‘failed’ to separate the natural and the cultural (as well as to separate work from leisure, and the sacred from the secular). They had failed, colonisers claimed, to make the transitions that modernity and industrial production required, whereby they ought to have separated themselves, as self-acting autonomous subjects, from their surroundings, in order to truly act upon a separate ‘nature.’ Instead, they ‘confused’ nature and culture, ascribing subjectivity to natural objects (often naming hillocks, groves and other features of the landscape) and refraining from that genuine productive activity which results from an ‘acting upon’ and a transforming of the landscape.

We do not have to deduce these divergent epistemologies of nature merely by reading archives against the grain; we are living at a time when Indigenous writing is being produced that looks not only back to history but forward, with hope, in the struggle against climate change, disaster-capitalism, and techno-solutionism. (Some examples, from a rich vein of recent writing: Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass, Joy Harjo, How We Became Human, Leanne Betasamosak Simpson, Rehearsals for Living).

The writing of Indigenous sciences into static pasts and European plant hunters into the shapers of modernity is now a familiar strategy, and undergraduates can skilfully cite Johannes Fabian’s critical anthropological insights from Time and the Other (1983). What Haitian-American anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot fought hard to articulate against professional historiography in Silencing the Past (1995) is now widely accepted and taken up in efforts to “decolonize the curriculum.” But without a thorough revisiting of the role of anthropology, history, and the biological sciences in the production of a time-based racialized narrative of scientific knowledge, disciplinary modes of thinking with roots in the eighteenth century continue to shape our twenty-first-century-course topics and film grammars.

Anthropology and History as disciplines were in formation at the same time that Botany was transforming and modernizing an amateur-oriented love of “natural history.” Together these disciplinary legacies of the eighteenth century facilitate a writing of nature, native, and time onto a scale off which all kinds of things can be read: hierarchies of civilization, scales of development, degrees of biophilia.

Greenwashing can happen today not just because of the venality of corporations but because Anthropology, History and Botany have laid the foundations of racial geopolitical thought. As critical and decolonizing as we might be, we do not yet have curricula that combine film criticism with histories of plant exchanges, oceanic with terrestrial histories, plantation economies with histories of law and jurisdiction, scientific societies with Indigenous and inter-racial love stories.

It is hard to articulate a twenty-first-century justification for continuing to teach Anthropology in departments separate from Indigenous Studies, the Biosciences in separate schools from Histories of early modern trade and travel, or Geography in departments that separate scientific and cultural methods. Disciplinary legacies often form the invisible structures that reproduce extractive forms of research and neocolonial narratives of progress, despite well-intentioned liberal calls to decolonize.

History and Transcendence

Film critic Daniel Garrett, who published the most comprehensive and enthusiastic engagement Proteus received, concludes his review with regret: “[N]o character in Proteus is free of history, nor could be in that time and place, and that is something that, to me, prevents the film from being profoundly transcendent.” This assessment underlies his conclusion: “I think Proteus is interesting, though not satisfying, and significant, though not necessarily important” (emphases in the original).

Garrett sees the historical allusions as a weakness of the film, arguing that historical embeddedness prevents the film from becoming a transcendent critique of racism. I have argued, here, that the film Proteus is powerful precisely because of its historical embeddedness. It is able to weave together histories of sexuality, epistemologies of colonialism, and Indigenous plant geographies in ways that few academic histories do. It opens the door for us to move from the contemplation of historical violence to the forging of new futures in dialogue with Indigenous writers and climate activists.

Universities and academic journals, divided into narrow specializations, remain in thrall to eighteenth- and nineteenth- century definitions of knowledge. The call for “transcendent” critiques of racism ignores the historical production of racism and the need to situate science historically in order to rob it of its theological/ transcendent claims. While the call for transcendence is undergirded by the well-meaning liberal desire to go beyond individual limits and to find common cause across racial and cultural difference, it often jettisons historical complexity, as if we could simply rise above the complex complicities that have made our nations, our communities, and our psyches. Proteus suggests that we have much work to do – not in transcending, or leaving behind, the arcane debates over historiography and geography, but in weaving them together into critical, resistant, joyful narratives that can speak to a new time.

Kavita Philip is President’s Excellence Chair in Network Cultures and Professor of English Language and Literatures at the University of British Columbia.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Aishwary Kumar for his broad, inventive conceptualization of conversations on After Life, to Cal Poly Pomona for their generous hosting, and to all the participants for their engagement. Gratitude also to Marjan Wardaki and participants at the Yale InterAsia workshop Botanical Knowledge in Motion: Plant Geography and Epistemic Traditions in and across Asia, 1850-1945. For bringing this essay to publication, thanks to polymath scholars Geeta Patel and Mary Chapman for insightful suggestions, to future historian of science Hui Wong for editing assistance, and to Robert Crews for patient encouragement.

footnotes

- 1 Easterby 2017, “On Diplomacy and Botanical Gifts: France, Mysore, and Mauritius in 1788,” in Batsaki, Cahalan and Tchikine, eds.The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century.

- 2 Nappi 2017, “Making “Mongolian” Nature Medicinal Plants and Qing Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century,” in The Botany of Empire.

- 3 Cited in Brockway 1979, p 103.

- 4 Markham 1862, Travels in Peru and India.