Europe’s Weather and the Future of History

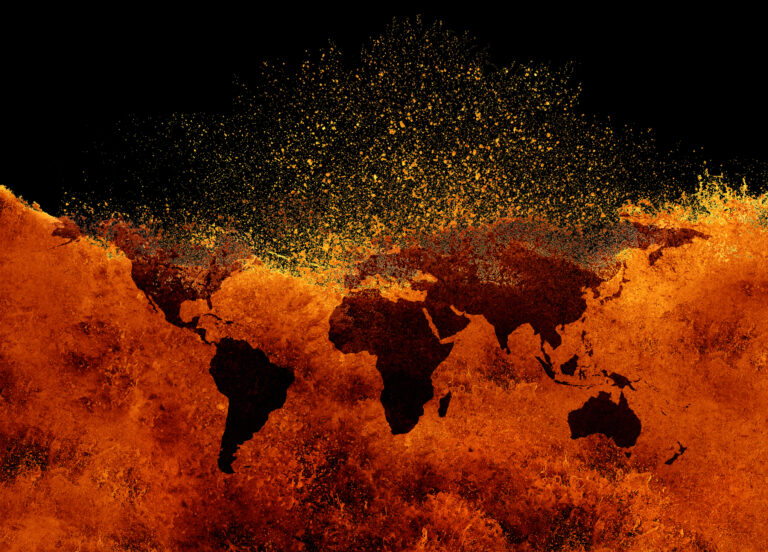

The landscapes associated with Homer and Cervantes are changing before our eyes. What does rapid climate change mean for the past, present, and future of Europe?

Europe’s recent unprecedented weather is cause for concern. The summer of 2022 proved so cruel that it required a rewriting of the history books. This past autumn and winter suggest it was no fluke.

Three unrelenting heatwaves in June, July, and August brought historic high temperatures to seven of Europe’s capitals. The mercury soared to 104°F in London, and to 105°F in Rome. If large cities had it bad, more rural areas had it worse. A small town in central Hungary broke 107° F. Northern Portugal’s Duoro Valley endured an unprecedented 116°F.

With heat came fire. By July, Europe had already suffered record levels of fire damage. Fires scorched over 1.2 M acres of land, four times the annual average, before August even started. Tens of thousands of Europeans, from Spain to Greece, were forced to evacuate their homes. The total cost of 2022’s summer blazes is over $8B.

Last summer’s drought was the worst in Europe in 500 years. Some 60% of Europe – an area the size of India – registered severe water shortages. Drought wrought Biblical visions of rivers running dry, fish skeletons cooking in sun-cracked mud, and cattle suffering in dead fields.

As rivers and reservoirs evaporated, Europe’s past began to emerge, portending nothing good. Messages carved on “hunger stones” by survivors of droughts in previous centuries minced no words. “If you see me,” warned one stone along the receding Elbe River, “then weep.” The ghosts of past cataclysms warned that bad harvests, high prices, and shortages of food and water are coming.

Europeans have already paid dearly. Heat-related deaths are hard to quantify, but the toll was certainly devastating. In mid-July, over 6500 people died of heat in Germany during a single two-week period. Experts in France estimate that 11,000 people perished since June. Thousands more died from Spain to Poland to the U.K.

The hot, dry weather has not been just a quirk of “global weirding.” For all its records, the summer of 2022 corroborated ample evidence that Europe’s climate is permanently changing. Average annual near-surface temperatures, key measures of global climate change, have increased nearly 2°C in Europe since the Industrial Revolution, twice the rate of the rest of the globe. And the warming trend is intensifying. The decade since 2012 has been the hottest in Europe since the late 19th century.

While hot summers come and go, the trend of unprecedentedly warm weather did not pass with the seasons. Late December witnessed a heat wave that brought temperatures 18° to 36°F warmer than average across the continent.

New Year’s Day 2023 broke records with balmy weather better suited to May than April. Temperatures climbed well above 60°F from the Netherlands to Belarus. Bilbao was over 77°F. One climatologist called the heatwave “totally insane.”

Climate change obviously poses fundamental challenges to Europe’s future. It also shapes how we understand its history, including both the meaning of its past and how it got to where it is today.

In 1949, the French historian Fernand Braudel, a forefather of environmental history, published a monumental study of Mediterranean Europe. In it, he argued that history is shaped far less by people or events than by the natural environment of the region. Braudel likened the environment to the deepest parts of the sea where change is gradual, repetitious, and cyclical. Human activities, from social practices to isolated events, could cause swells in the current or foamy crests of waves, but they would always be steadied by the profundity of the environment.

Unimaginable to Braudel was that human actions could so fundamentally transform, in a generation or two, the environment that shapes history.

What, then, does rapid climate change mean for the past, present, and future of Europe?

Changes in climate have already altered the European landscape. Southern Europe, from Portugal to Bulgaria, is undergoing desertification, the degradation of land due to heat and drought, at an alarming pace. As much as 75% of Spain will become arid or semi-arid in the coming decades. Italy, France, and the Balkans are following, as the heat, drought, and fires of recent years suggests.

The impact of desertification heralds more than a change in the weather. Europe’s agricultural products, from the myriad cheeses to world-class wines, are under threat. Warmer temperatures have already moved the champagne grape harvest weeks earlier in the year. More serious still, warmer weather will eventually change the chemistry of the grapes themselves, endangering an age-old way of life and the industry built around it.

Europe produces half of the world’s wine with revenues reaching $150B last year. Equally important, wine is a draw that helps make Europe a culinary and cultural destination. As temperatures peak and fires burn, many Europeans wonder if tourists will stop coming. Italy and Greece have the most to lose, as the tourist industry employs millions of workers and represents 13% and 18% of their respective GDPs.

Droughts last summer dried Europe’s great rivers to a trickle. In Germany, the Rhine dropped to a depth of just 14 inches, making commercial shipping impossible. Cargo transport alone contributes about $80B to the continent’s economy. The knock-on effects are even more costly. Boats deliver grain to international markets, and coal to power plants, steelworks, and other industries.

Complicating matters is that climate change is also causing seas to rise, threatening Europe’s port cities, beaches, and coast lines. Venice is particularly vulnerable. The Italian city has always experienced occasional flooding, known as acqua alta, but rising sea levels have made flooding more and more common. The City of Canals has flooded more times in the last twenty years – some 160 times – than in the previous century. More worrisome still is that creeping salt water corrodes brick foundations of the city’s prized medieval and Renaissance structures.

And last summer, the usually white-capped mountains of the continent appeared remarkably rocky. Lower altitudes from the Pyrenees to the Balkans used to snowfall started 2023 rocky and barren. While ski resorts struggle, the lack of snow this winter threatens to leave already depleted lakes and reservoirs in dire need of replenishment come spring.

The landscapes associated with Homer and Cervantes are changing before our eyes. The waterways that fueled have European capitalism for centuries are drying up. Iconic buildings and ways of life – from the attractions that have long drawn travelers to the food and drinks served on European tables – are in danger of changing forever. Such changes call into question what we talk about when we talk about Europe.

If climate change is transforming the landscape, cultural practices, and economic vitality of the continent, it also forces a reassessment of Europe’s historical place in the world.

Europe is not a passive bystander in the story of climate change. The current countries of the EU, plus the United Kingdom and Russia, have historically contributed more to global climate change than any other part of the world. Since 1750, Europe has produced about 28% of the planet’s cumulative carbon dioxide emissions, slightly more than the United States and more than twice that of China. As a percentage of the global population, Europe’s contribution to climate change is even more pronounced.

While the continent has been unseasonably warm, many parts of Europe’s former empires has suffered in ways even more destructive. Pakistan endured catastrophic summer floods, with over 30 million people left homeless. Drought left more than 16 million people without reliable water from Ethiopia to Kenya. Again, these are more trend than anomalies. Vast swaths of the Sahel have been undergoing desertification for years, creating a permanent “hunger belt” along the southern border of the Sahara from Mauritania to Southern Sudan.

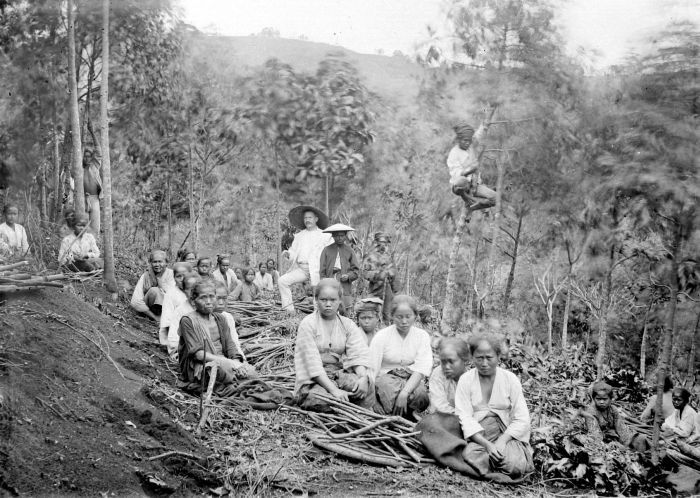

Europe alone is certainly not to blame for global climate change. But if Europe’s industrialization fueled its 19th-century imperial conquests, the legacy of that history, and the relations it forged, continues to shape its international obligations. And some of these former colonies are starting to push for climate-related reparations.

As Europe’s former empires have widely refused to pay reparations for, or often even to acknowledge the devastating impact of colonialism, it is likely new climate demands will be similarly ignored. But there is no doubt that many former colonies will add droughts and floods to their lists of historical complaints against Europe. The murderous famines that once plagued parts of the French and British empires, it seems, continue with different causes, but similar responses: denial of responsibility and neglect.

Climate change has spurred a kind of reckoning in Europe. The EU has adopted aggressive policies aimed at cutting greenhouse gases by 55% over 1990 levels by 2030, introducing carbon removal programs, and increasing renewable energy production. But with the planet at a “disastrous” tipping point according to most climate scientists, European aims of being carbon neutral by 2050 may well be too little late.

Just as Europe isn’t solely responsible for climate change, it cannot solve it alone. The international influence Europe once brokered seems anemic in 2023. Climate defenders in Europe have thus far failed to convince the United States and other global powers to take more aggressive steps to curb carbon emissions. Indeed, the war in Ukraine has sadly seen many politicians even in Europe double-down on a reliance on fossil fuels.

Fernand Braudel believed the environment to be foundational to Europe’s rise to global power. As the environment changes, we can only wonder what sort of sea change awaits the continent, as well as the planet. The historic records of Europe’s summer of heat and fire are sure to be broken. And with every new record must be new recognition of what is being lost, in Europe and abroad.

JP Daughton is Professor of History at Stanford University. His most recent book is In the Forest of No Joy: The Congo-Océan Railroad and the Tragedy of French Colonialism (W. W. Norton, 2021).